Fantastic 116-Year-Old Color Pictures of the Philippines

Until recently, I thought old folks only had black-and-white pictures. Rarely do you see colorized versions of these photos, especially those from the 19th century. And if you do, they are usually the modern Photoshopped versions, not the authentic ones.

So it was with great surprise when I recently came across with a gem of a book called “Color Photos of America’s New Possessions.” Frank Tennyson Neely, a former schoolteacher who operated a publishing business in America, released the book to the public in 1899. It was reprinted the following year.

Also Read: 20 Remarkable Colorized Photos Will Let You Relive Philippine History

You probably have seen some of these photos already, but not with vibrant colors. And that makes this photo collection special: the natural colors make the pictures more real, bringing us back to the year 1899 when the Philippine-American War was in its earliest stages.

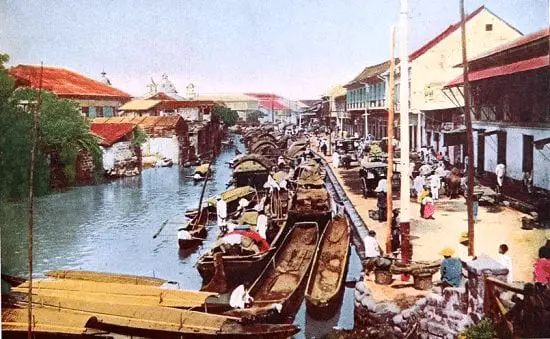

1. Estero de la Reina.

As you can recall, Manila of the 1890s was fondly called by some writers as the “Venice of the Orient.” This is because of the city’s picturesque canals, which include Estero de la Reina along Calle Tetuan.

Also Read: Whatever Happened To Binondo’s Lift Bridge?

The canals back then kept commerce alive by allowing boats to travel and transport goods throughout the city. I wonder what our ancestors would feel when they see Estero de la Reina today. What was once a place teeming with life is now a creek so filthy even rats wouldn’t dare swim on it.

2. San Sebastian Church.

The Americans were probably in awe when they first saw the San Sebastian Church only a few years after its completion. Declared a minor basilica by the Augustinian Recollects, San Sebastian is the only all-steel church in the country.

Related Article: “The Most Beautiful Street in Manila”

Spanish architect Genaro Palacios reportedly designed it after the gothic cathedral in his home country, while no less than Gustav Eiffel (the engineer behind the world-famous Eiffel Tower) joined the team who conceptualized the steel structure.

Today, the church is being eaten by rust as a result of water leaks, but ongoing restoration will hopefully reverse the damage.

3. Anda Monument.

Before it hit the headlines in late 2014 because of the government’s plan to transfer it to yet another location, the Anda monument was nothing but an obscure landmark. It is so unpopular that one DPWH official said matter-of-factly that it has “no historical value.”

But whoever said that had no clue what he’s talking about. The Anda monument was built in 1871 in honor of Simon de Anda y Salazar, who, after successfully leading the resistance against the British invaders, was appointed governor-general of the Philippines.

Also Read: Remembering Magellan’s Monument

The original monument (as seen in the photo) was erected near the mouth of the Pasig River. It suffered serious damage during WWII. Later in the 1960s, it was reconstructed and transferred to another location to give way to the construction of the Del Pan Bridge (now Roxas Bridge).

For years, it served as the centerpiece of the Anda Circle along Bonifacio Drive and was later blamed for causing traffic congestion. In 2014, DPWH has had enough and decided to replace the circle with a road intersection and transfer the monument to the Maestranza Park in Intramuros.

4. Paseo de Luneta.

Luneta was such a big deal back in the day, so much so that Manila’s elite frequented this place to have their afternoon strolls and evening social activities.

The area was formerly a marshy patch of land which, in 1820, was transformed into Paseo de Luneta overlooking Manila Bay. The 19th century Luneta not only served as a leisure park but also execution ground where rebels and mutineers met their fate.

Also Read: The Controversial “Luneta Tower” That Was Never Built

Bonus Trivia: Helen “Nellie” Herron Taft, wife of the former governor-general of the Philippines and later US President William Howard Taft, was so impressed with Luneta that she modeled Washington’s Potomac Park after it. She once said:

“I determined, if possible, to convert Potomac Park into a glorified Luneta where all Washington could meet, either on foot or in vehicles, at five o’clock on certain evenings, listen to band concerts and enjoy such recreation as no other spot in Washington could possibly afford.”

5. Escolta.

When Uncle Sam took over the Philippines, much of the transformation took place in its city capital. The center of commerce gradually moved from Binondo’s ‘Chinatown’ to an area bounded by Plaza Santa Cruz, Escolta, Plaza Goiti, and Avenida Rizal.

READ: 20 Beautiful Old Manila Buildings That No Longer Exist

Among these four, Escolta became the place of luxury. No wonder it has been dubbed as the ‘Queen of the Streets.’

The Manila’s elite frequented Escolta to shop inside upscale department stores such as La Puerta del Sol (see photo above) and Estrella del Norte; watch movies at Lyric and Capitol theaters; and buy expensive goods from luxury boutiques such as Rebullida (Swiss watches), Riu Hermanos (leather products), and Pillicier (imported fabrics).

6. Intendencia (Aduana Building).

Designed by the Spanish engineer Tomas Cortes, this building once housed the treasury department of the Spanish colonial government. It remained a treasury building even after the Americans arrived because the new colonizers thought it was “well-adapted for the purpose and easily guarded.”

The pre-war Aduana later became home to different offices: Casa de Moneda (Mint), the Customs, and the Intendencia General de Hacienda (Central Administration). After sustaining significant damage during the Liberation of Manila, the building was reconstructed and once again housed government offices, including Commission on Elections.

Related Article: The 8 Most Haunting ‘Abandoned’ Places in the Philippines

In 1979, a huge fire destroyed the building. Soon thereafter, Presidential Letter of Instruction No. 966 was released to have it restored and become the future home of the National Archives. As of this writing, the restoration project is still ongoing.

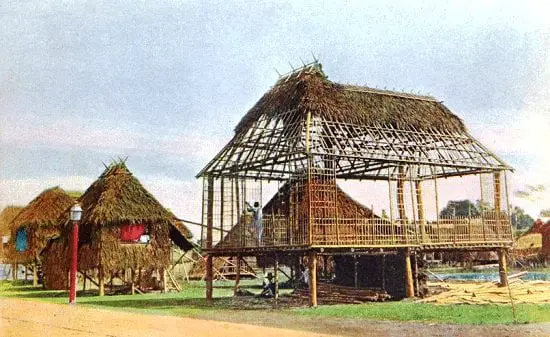

7. Bahay-Kubo (Traditional Filipino House).

This photo shows how a traditional Filipino house, known as bahay-kubo (nipa hut), was constructed in the late 19th century. Little has changed since then, but variations of the native Filipino house have been developed in other parts of the country, where people build their dwellings based on their existing culture and climate conditions.

Also Read: 9 Interesting Facts You Might Not Know About Batanes

Architect Manuel D. C. Noche takes us inside a typical bahay-kubo:

“Native huts….include steep roof over a one-or-two room living area raised on posts or stilts one to two meters above the ground or over shallow water. Some huts have balconies. Floors may be of split bamboo to allow dirt and food scraps to fall through to pigs and poultry. The space beneath the hut may be used for storage or as a workshop; it also allows air to circulate and safeguards against flooding, snakes, and insects.”

8. Cockfighting.

Cockfighting is to the Philippines as bullfighting is to Spain. It became a favorite national pastime in the 18th and 19th centuries, so much so that the Spanish colonial government imposed taxes to regulate it. As a result, it became a lucrative source of income for the colonizers, and it remained so until the arrival of the Americans.

Also Read: A Look Into The Life of Paco Roman, That Other Guy Who Died With Antonio Luna

When Uncle Sam started penetrating the Filipino society, cockfighting became one of its targets. In fact, the American government went as far as including morality lectures in the primary school curriculum just to prove to the natives how barbaric their customs were–cockfighting included.

Bonus Trivia: Cockfighting has been a favorite Filipino sport since time immemorial. And it’s even older than most people think.

According to the book “The Cockfighting: A Casebook” by Alan Dundes, an early form of cockfighting was recorded in Butuan before the Spanish colonizers arrived. The same thing was witnessed in Palawan by Antonio Pigafetta, the famed chronicler who joined Ferdinand Magellan in a journey around the world.

9. Corregidor Island.

You’re looking at a photo of Corregidor years before the Americans turned it into an island fortress. They wanted to build strong defenses in the area shortly after declaring the Philippines as their new territory in 1899, and they chose Corregidor as their headquarters.

READ: 7 Famous Historical Figures You Didn’t Know Visited The Philippines

The decision of the new colonizers was obviously strategic since Corregidor is the largest among the five volcanic islands surrounding the entrance of Manila Bay. During the first few years of the 20th century, the tadpole-shaped island transformed into a fortress called Fort Mills, named after Major-General Samuel M. Mills. It was equipped with “nine major batteries mounting 25 modern coast artillery weapons.”

In 1942, Corregidor Island fell into the hands of the invading Japanese army. Three years later, the Allied forces came back to reclaim it and all the other island fortresses.

10. Barasoain Church.

The Barasoain Church in Malolos, Bulacan had rough beginnings. The original church, made of light materials, was engulfed by fire in 1884. But shortly after its reconstruction, Barasoain became an important landmark that saw the rise and fall of Aguinaldo’s government.

Also Read: 11 Things You Never Knew About Gregorio Del Pilar

It was in 1898 when the constitutional convention was held in the church, followed by the proclamation of Malolos as the new capital of the Philippines. A year later, the newly-established First Philippine Republic made Emilio Aguinaldo its president.

The photo above shows the church during the first day of the American occupation. After Aguinaldo and his men left, Gen. Arthur MacArthur made the church his headquarters.

11. La Loma Church.

Soon after seizing control of La Loma on February 5, 1899, Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur made its church his new headquarters. He and his men, the Second Division of the Eight Corps, stayed here as they prepared their strategies for the Battle of Caloocan that would take place a few days later.

Also Read: 13 Facts That Prove Antonio Luna Was An All-Around Badass

MacArthur was up against thousands of Filipino soldiers under the fiery Gen. Antonio Luna. On the day of the battle, John F. Bass, a correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, was one of the eyewitnesses:

“From La Loma church you may get the full view of our long line crossing the open field, even, steadily, irresistibly, like an inrolling wave on the beach. Watch the regiments go forward, and form under fire, and move on and on, and you will exclaim, “Magnificent,” and you will gulp a little and feel proud without exactly knowing why. Then gradually, the power of that line will force itself upon you, and you will feel that you must follow, that whatever that line goes you must go also.”

In the end, the Americans won the battle. As for Gen. Luna, their defeat opened his eyes to the deficiencies of the Filipino army and prompted him to open a military academy to help correct those mistakes.

12. Philippine funeral.

Filipinos have always believed in the afterlife, and our practice of burying the dead reflects that. When the Spanish colonizers arrived, our ancestors were introduced to the idea of a cemetery. Its Filipino translation, sementeryo, came from the Spanish “cementerio” or also known as “kampo santo” (a combination of “campo” or field and “santo” or saints).

Also Read: 6 True Stories From Philippine History Creepier Than Any Horror Movie

Up until the 19th century, Filipino Catholics were usually buried within the church grounds, while important personalities were interred inside the church. A usual feature of cemeteries, like in the old Paco cemetery, was the required rental fee. Coffins placed inside the niches or “cubby holes” were removed as a consequence for not paying the fee. The remains were either left in the open or placed in a vault below.

Selected References

Berhow, M. (2012). American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay: 1898-1945. Osprey Publishing.

City Government of Malolos Official Website,. Barasoain Church Highlights. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/tasYL4

Color Photos of America’s New Possessions. (1899). Chicago.

Dundes, A. (1994). The Cockfight: A Casebook. Univ of Wisconsin Press.

Hedman, E., & Sidel, J. (2005). Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century: Colonial Legacies, Post-Colonial Trajectories. Routledge.

Macas, T. (2015). A walk through Rizal Park on the National Hero’s 154th birthday. GMA News Online. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/QFuxKN

National Archives of the Philippines,. History of the Intendencia (La Aduana) de Manila. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/0lWEZe

Palafox, Q. Cemeteries of Memories Where Journey to Eternity Begins. National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/V4OvR3

Santos, R. (2014). FAST FACTS: The Anda Monument. Rappler. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/Og4qwy

Silbey, D. (2008). A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899-1902. Macmillan.

Sison, N. (2014). Anda Monument: Reminder of a crucial period in PH history. Vera Files. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/tRvW1C

Taft, H. (2004). Recollections of Full Years: (Annotated). Big Byte Books.

Zulueta, L. (2015). Rust corroding all-steel San Sebastian Church. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 18 January 2016, from http://goo.gl/sbGkur

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net