10 Surprising Facts About Death Penalty In The Philippines

For Filipinos, few issues can be so polarizing yet undoubtedly interesting at the same time as that of the death penalty.

After all, some of the most memorable moments of our history have involved capital punishment (the Gomburza’s garrote, Jose Rizal’s firing squad, etc.).

Although we won’t enter in the unending whirlpool of debates and choose which side we’re on, we would like to share some of the more interesting stories and facts about our country’s on-and-off brush with the death penalty.

Also Read: Pinoy Historical Figures Who Died in Shocking Ways

1. The pre-Spanish Filipinos practiced it, albeit infrequently

While not capital punishment in the sense that it was not rendered for the sake of the state, the pre-Spanish Filipinos did practice the death penalty. However, they practiced it infrequently at best.

Death sentences were regularly commuted to fines, flogging, or slavery. Out of the three, slavery was the most common form of commutation since the pre-Spanish Filipinos found it more practical to have a slave work in their fields and lands.

Related Article: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

And unlike what the proven hoax Code of Kalantiaw would like us to believe, the condemned were not subjected to unusual and cruel punishments such as being eaten by ants or thrown in boiling water. Instead, they were executed via the more-common methods of decapitation and hanging.

2. The Spanish also didn’t use it much either

Another misconception about Spanish rule in the Philippines blown way out of proportion is the implementation of the death penalty during their rule. While executions did indeed happen, they only commonly occurred during rebellions and uprisings.

In cases of treason, rebellion, or any other crime which endangered Spanish sovereignty, the death penalty was frequently employed to quell the disturbance.

Also Read: 7 Myths About Spanish Colonial Period Filipinos Should All Stop Believing

In times of relative peace, however, the Spanish did not bother to employ capital punishment as much. In fact, out of more than 1,700 murder convicts condemned to die from 1840 to 1885, the Spanish only executed 46 of them—an evidence that they were far more concerned with maintaining their authority on the natives than killing them off en masse.

In a twist, it was the Americans rather than the Spanish who enacted more laws (the Sedition, Brigandage, and Flag Laws) mandating the death penalty as a means of suppressing dissent among Filipinos.

READ: 8 Dark Chapters of Filipino-American History We Rarely Talk About

3. The Philippines had a club of pro-death penalty judges

During the periods when the death penalty still operated, there existed a group of judges who strongly advocated capital punishment and who were only too eager to give out the death penalty. Known as the Guillotine Club, the group was founded in 1995 by Quezon City judge Maximiano Asuncion for judges who handed out death sentences.

Related Article: The Last Words Of Leo Echegaray

By his reasoning, if criminals could form syndicates to sow fear among ordinary people, then law-abiding citizens such as judges should be able to put up their own group to scare off criminals.

Asuncion himself was said to have given out seven death sentences during his career. In fact, it was Asuncion who presided over the high-profile case involving Leo Echegaray whom he subsequently sentenced to death.

In a twist of fate, Asuncion did not live to see the sentence carried out—he died of a heart attack two years before Echegaray’s execution in 1999.

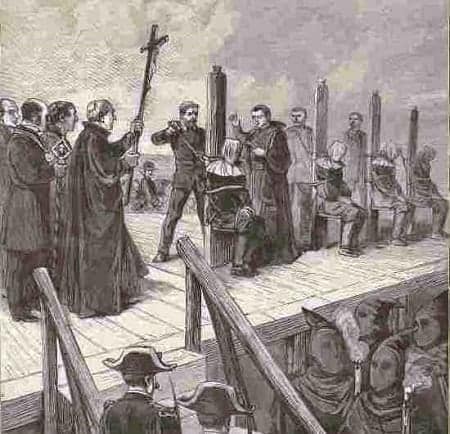

4. The Catholic church was once pro-death penalty

There used to be a time when the Catholic Church actively campaigned for the death penalty. During the Philippine Revolution, Manila Archbishop Bernardino Nozaleda openly called for Filipino rebels to be exterminated by “fire, sword, and wholesale executions.”

With his endorsement, Spanish authorities regularly conducted public executions of Filipino revolutionaries. It can be said Nozaleda was also indirectly responsible for Jose Rizal’s death when he orchestrated the ouster of the conciliatory Governor Ramon Blanco with the iron-fisted Camilo de Polavieja.

Also Read: 9 Things You Didn’t Know About The Catholic Church In The Philippines

Nozaleda also several times attempted to change sides. With the Americans’ arrival, he first appealed to Emilio Aguinaldo for a Spanish-Filipino alliance against what he viewed as a Protestant threat. When the Americans were winning, he also approached them for an alliance but was rebuffed.

Ultimately, even his own people in Spain rejected him—the city of Valencia once denied him entry following his appointment as its archbishop. He resigned shortly thereafter.

5. The Philippines had the world’s second-largest death row population among democracies

Outside of such states as China and countries in the Middle East, the Philippines—before it abolished the death penalty in 2006—used to have the world’s second-largest population of death row prisoners, pegged at an estimated 1,200 people.

READ: 23 Things You Didn’t Know About President Rodrigo Duterte

According to Amnesty International, the commutation of those sentences by former President Gloria Arroyo also gave the Philippines the record of having conducted the biggest number of commutations in a single sitting anywhere in the world.

Of course, the democratic country with the largest death row population is none other than the United States. Since 1995 until the present, its death row convicts have averaged 3,000 per year.

6. A governor nearly ended up in the electric chair

In what would have arguably been one of the biggest upsets against a political dynasty, one governor nearly met his end in the electric chair.

Rafael Lacson, the governor of Negros Occidental who ran the province like his own personal fiefdom from 1949 to 1951, was sentenced to the electric chair in 1954. This was after being found guilty for the murder of Moises Padilla, an opposition candidate who ran for mayor in the town of Magallon in 1951.

Even after being threatened and harassed, Padilla—a war veteran who had the backing of then-Defense Secretary Ramon Magsaysay—continued his run. Even though his candidate won the elections, Lacson ordered the apprehension of Padilla ostensibly on the grounds of sedition and illegal possession of firearms. A few days after his “arrest,” Padilla’s bloodied and bullet-riddled body was found in the town plaza.

Also Read: 6 Reasons Why Ramon Magsaysay Was The Best President Ever

The brazenness of the murder spurred Magsaysay himself to personally go to Magallon to pick up Padilla’s body and bring it to Manila for an autopsy and proper burial. In the end, however, Lacson’s death penalty was reduced to life imprisonment due to the needed number of votes coming up short in the Supreme Court.

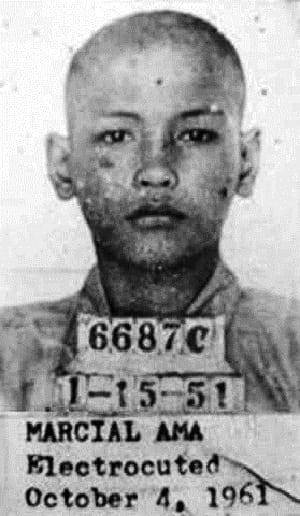

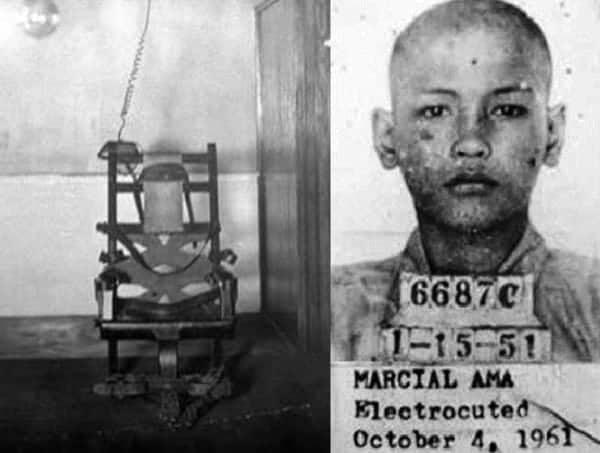

7. We have executed a very young convict before

With the uproar nowadays over the Pangilinan Law which critics say have essentially allowed minors to commit crimes with impunity, a time occurred when the country really did—and could legally—execute a minor since they were considered adults at the time.

Recommended Article: 9 Extremely Notorious Pinoy Gangsters

In this case, the offender was none other than Marcial “Baby” Ama who was allegedly only 16 years old when he was executed via electric chair. At the time, the law considered the legal age for men and women to be 16 and 14 respectively.

Editor’s note: The writer’s claim that Ama was executed at the age of 16 is questionable. Although we have confirmed that he died on October 4, 1961, his real age at the time of death remains a mystery. However, if we believe the claim that he’s 16 when he died, he would have been born in 1945 and was only 6 years old when the mugshot (dated 1-15-1951) was captured. He most likely died young but not as a teenager as what this entry previously claimed.

Ama himself earned his sentence after leading one of the biggest jail riots in history which resulted in the deaths of nine inmates, one of them having been beheaded.

The Supreme Court imposed the death penalty after finding him guilty for stabbing to death a man named Almario Bautista during the riot.

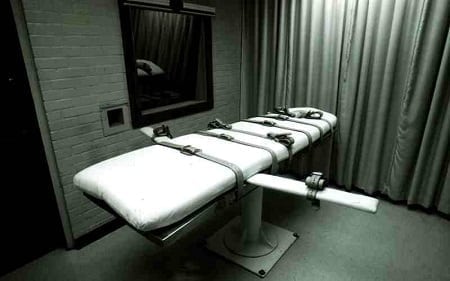

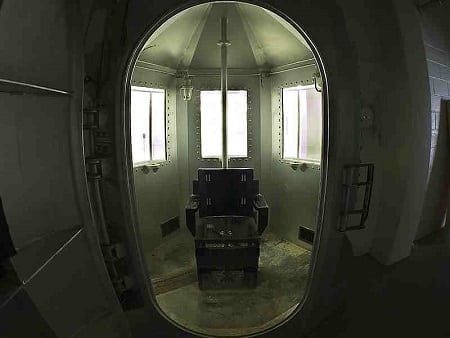

8. We nearly employed the gas chamber instead of lethal injection

Were it not for the Americans’ refusal to give us one, we would have ended up using the gas chamber—which is still legal in four US states by the way—instead of lethal injection.

When President Fidel Ramos brought back the death penalty with Republic Act 7659 in 1993, he envisioned the gas chamber to replace the electric chair as stipulated in the third paragraph of Article 81 “as soon as facilities are provided by the Bureau of Prisons.”

Also Read: 15 Weird Laws Filipinos Still Have To Live With

However, the Americans—for one reason or another—rejected Ramos’ bid to purchase the necessary materials from them, although they did successfully convince him to buy the equipment for lethal injection instead. As a result, the law had to be changed again to provide for lethal injection as the country’s method of execution.

9. Only the Philippines and the US have ever used the electric chair

Believe it or not, only two countries in the world have ever used the electric chair—the United States and the Philippines (in fact, it is still being used in certain US states today).

The Philippines adopted electrocution after the US brought in an electric chair in 1926. The country continued to use the chair until 1976 when the firing squad replaced it as the preferred method of execution.

In its 50-year career, the electric chair took the lives of 86 death row prisoners, among them the three rapists of actress Maggie dela Riva, Baby Ama, and Manuel Roxas’ would-be assassin Julio Guillen.

10. A busy phone line led to a convict’s execution

While the Philippines has had no incident of botched executions, it did have one instance where a busy telephone line resulted in a convict’s execution before it could have been postponed.

Minutes before the scheduled execution of convicted rapist Eduardo Agbayani on January 25, 1999, President Joseph Estrada received a call from his spiritual adviser Bishop Teodoro Bacani telling him Agbayani’s three daughters—his victims—were willing to forgive him. Estrada then tried calling prison officials to stop the execution but only received fax tones and busy signals.

Also Read: 10 Unforgettable Pinoy Politicians We Wish Were Still Alive

It was later discovered that Estrada did not know he was not using a direct line specially installed for the very purpose of stopping an execution. When he did manage to connect at 3:12 PM, Agbayani was unfortunately already dead at 3:11 PM—a mere difference of a single minute.

References

Amnesty International,. (2006). Philippines: Largest ever commutation of death sentences. Retrieved 11 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/XqSVCp

Daza, J. (1995). Jun Simon’s new clothes. Manila Standard, p. 37. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/Jtxa8k

Gluckman, R. (1999). Waiting to Go. Asiaweek Magazine. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/UkWJZh

Johnson, D., & Zimring, F. (2009). The Next Frontier : National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia(p. 106). Oxford University Press.

Mintz, M. (2006). Crime and Punishment in Pre-Hispanic Philippine Society. Intersections: Gender, History And Culture In The Asian Context, (13).

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff, vs. RAFAEL LACSON, ET AL., accused., G.R. No. L-18188 (SUPREME COURT 1961).

The Economist,. (1999). The Philippines: Capital Crimes. Retrieved 11 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/5kpDkJ

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee, vs. MARCIAL AMA Y PEREZ, ET AL., defendants. MARCIAL AMA Y PEREZ, defendant-appellant., G.R. No. L-14783 (SUPREME COURT 1961).

Tobias Gajilan, A. (1995). Filipino judge forms ‘guillotine club’ to promote death penalty. The Filipino Express. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/hBKO3S

UCANews.com,. (1999). Pardoned Convict is Executed Due to Telephone Tangle. Retrieved 11 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/Ju4yME

Additional References:

Maximum Security by Karen Farrington

Death Watch: A Death Penalty Anthology by Lane Nelson, Burk Foster

Government and Politics of the Republic of the Philippines by Gregorio F. Zaide, Sonia M. Zaide

Devil’s Causeway: The True Story of America’s First Prisoners of War in the Philippines and the Heroic Expedition Sent to Their Rescue by Matthew Westfall

The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World by Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson

Magsaysay: The Leader of the Masses by Aurelia del Fierro

Criminology and Criminal Justice Systems of the World: A Comparative Perspective by Peter O. Nwankwo

The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia by Manoa David T. Johnson, Franklin E. Zimring

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net