Why Do Filipinos Love To Eat Rice? (And Other Yummy Pinoy Food Facts)

We Pinoys are certified foodies. Whether it’s a street food to tame our growling stomachs or an occasional gourmet dish that blows our budget, Pinoys just love to sit down and try anything edible.

And as a true-blue Pinoy, we also love to share the experience with our foreigner friends. The way to a tourist’s heart, after all, is through his stomach.

But how can you explain the Pinoy food culture to outsiders if you personally don’t know how it started? These quick bits of delicious food facts should give you a head start.

Also Read: Top 10 Most Bizarre Filipino Foods

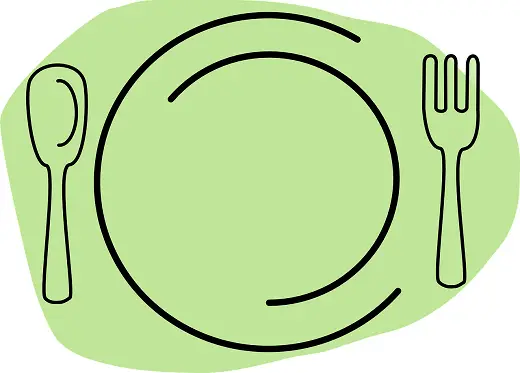

Why do Filipinos love to eat rice?

Rice is a staple in the Filipino diet. Many of us are unable to go a day without eating even just half a cup.

Our love affair with rice can be traced to pre-colonial times. The earliest evidence of the presence of rice in the country—which came in the form of carbonized organic deposits—dates back 3,500 years. It is believed that the seafaring Malay people, who arrived in the archipelago after the Negrito, were responsible for introducing rice to the pre-Spanish diet.

Also Read: 12 Surprising Facts You Didn’t Know About Pre-Colonial Philippines

But here comes the interesting part: Rice was not the original Filipino staple food.

In a paper written for the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. of Ateneo de Manila University reveals that our ancestors preferred “taro, yams, and millet” for their daily sustenance.

Rice, on the other hand, was produced in limited quantities; hence, it was mostly consumed by members of the upper class. It only became more common during Spanish colonization when rice production dramatically increased with the introduction of plow technology and a more efficient irrigation system.

Eventually, the food of the elite suddenly became available to everyone and had since become an indispensable part of the Filipino food culture.

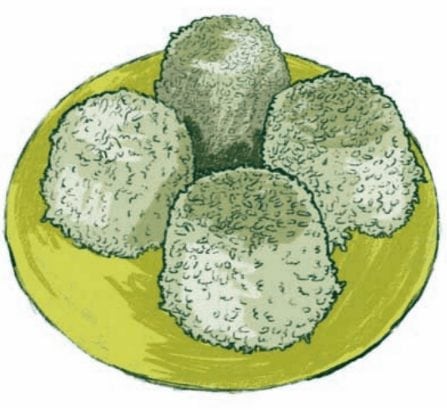

Is Adobo an original Filipino dish?

Experts don’t seem to agree on the roots of adobo in the Philippines.

Writer and historian Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, for instance, believes that the dish may have come from Mexico where adobo is known as a sauce made of lemon juice (instead of vinegar), tomatoes, garlic, pimentos, and other spices. When Mexicans came to the Philippines, they probably cooked their own version of adobo, then passed it on the natives who incorporated their own twist to the recipe.

Others say that adobo was introduced by the Spaniards; the term, after all, originates from the Spanish root word adobar, which means marinade.

Also Read: 7 Myths About Spanish Colonial Period Filipinos Should All Stop Believing

However, food historian Raymond Sokolov begs to differ. He asserts that adobo is, indeed, an original Filipino dish. It was only when the Spanish colonizers arrived in the archipelago and saw the similarity of the local version with theirs that the dish earned its present name.

In fact, a dictionary made by Pedro de San Buenaventura in 1613 contains the words “adobo de los naturales.”

Award-winning food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria also suggests that the Filipino adobo may have a French association. The Spanish word adobar came from the French word adober which originally meant‘to dress a knight in armor.’

When the word made its way into the Spanish vocabulary, it adopted a slightly altered meaning: ‘to dress meat,’ particularly in vinegar. This probably explains why France has its own version of adobo—known as “daube”—a dish traditionally cooked in a clay vessel just like its Filipino counterpart.

Putting all these in perspective, we may conclude that adobo deserves to be called our national dish. It may possess a name rooted to a foreign word, but its undeniable local flavor, with its many interpretations across Filipino households, is still uniquely our own.

From the pre-refrigeration days until now, adobo remains a symbol of our history—molded by Filipino minds, made richer by intercontinental influences.

Why do Filipinos use spoon and fork?

Just like eating rice, the custom of eating with a spoon and fork is something we share with our Asian neighbors. For us, these cutleries are inseparable—the absence of either one will take the joy out of eating Filipino foods. Heck, we even have giant wooden spoon and fork displayed on our dining rooms to prove their iconic status.

But why the affinity for using these eating utensils?

As common sense would tell us, both the tropical climate and the absence of refrigeration forced our ancestors to chop ingredients into smaller portions and cook dishes for longer periods. The result was a compendium of Filipino foods that are soupy and softer—dishes that no longer require the use of knives.

Also, the bland white rice is always paired with a viand (the word “ulam,” after all, means “to be eaten with rice”). To fully enjoy the meal, one simultaneously places small amounts of ulam and rice on the spoon with the help of the fork before swallowing the mixture, rather than consuming them separately.

According to the late food columnist Doreen Fernandez, it was the Spaniards who first brought the custom of eating with cubiertos to the Philippines. The idea was later reinforced by the Americans at the turn of the century.

Also Read: 27 Things You’ll Only See in the Philippines

Inquirer columnist Isagani Cruz once shared how his grandfather was employed by the American government to help in propagating the use of spoon and fork as eating utensils among rural folk. A 1914 news report published by the Daily Kentucky New Era also details how the Americans taught Filipino schoolchildren proper table manners—including the “use of knife, fork, and spoon”—through role-playing.

Historically speaking, primitive spoons made of shells antedated the knives which were originally used as weapons. The fork came much later. It is said that a Greek princess brought a “two-tined gold fork” to Italy in 1071, and from there, the idea spread throughout Europe and the Americas. No less than George Washington is being credited for popularizing it in the New World.

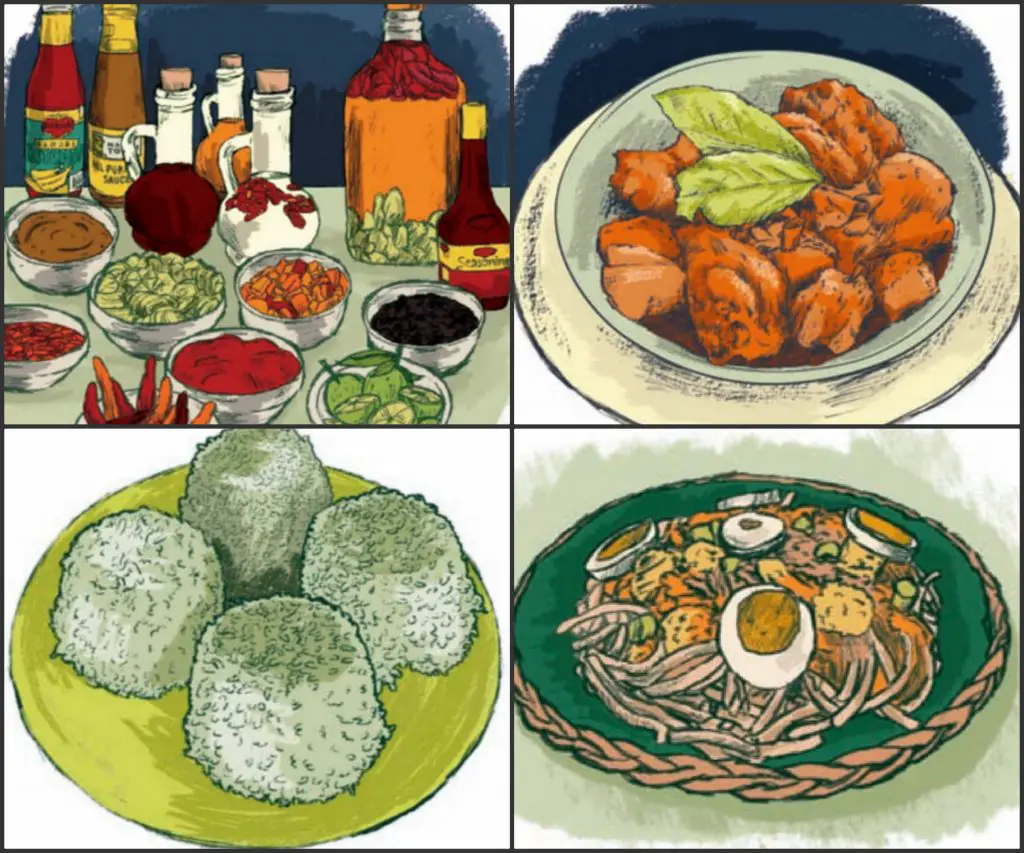

Why do Filipinos love ‘sawsawan’?

The idea of sawsawan is not a recent innovation. Lapu-Lapu was known to have loved chili-dipping sauces , as seen by Magellan and his men in 1521.

It’s not a Filipino invention either; most Asian countries have their own versions as well.

In the book “Palayok: Philippine Food Through Time, On Site, In The Pot” by noted food critic and cultural historian Doreen Fernandez, sawsawan is described as a “way of fine-tuning the taste of the dish to that of the individual diner.” It’s a way for us to be actively involved in the dining experience—a far cry from the French cuisine, wherein the chef has sole authority over the dish.

This explains why we have a sawsawan for every Filipino dish imaginable. We want our food not to be too salty, too sour, or too sweet so we have sauces to balance things out—like kalamansi for the salty pansit or patis for sweet dishes like tocino or lechon paksiw.

Also Read: 13 Amazing True Stories Behind Classic Filipino Brand Names

Interesting Trivia: The word toyo originated from the Fookienese term for soy sauce, pronounced as “taw-yu.” The Filipino word for vinegar (suka), on the other hand, was derived from either Chinese chho or the Sanskrit cukra which, when pronounced in Pakrit, sounds like its Tagalog counterpart.

Why do we call local eateries “carinderia”?

As Spanish Filipinologist Wenceslao Retana discovered in the 1920s, the origin of carinderia can be traced to the word kari which means “spice,” or what we know today as “curry.”

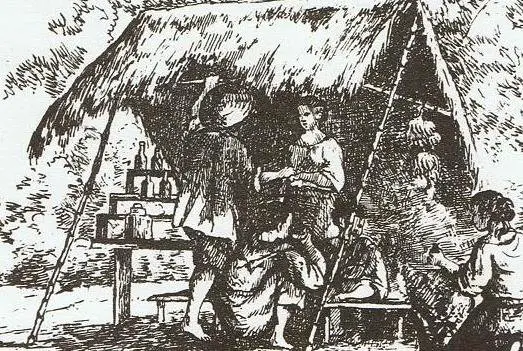

As to how it gave birth to the name of local eateries, we have to go back to the late 18th century, specifically during the British invasion of Manila (1762-1764).

For some reason, hundreds of Sepoys (a term referring to Indian soldiers who served under British command) left the Royal Army and settled in Taytay and Cainta with their Filipina wives.

Also Read: Why there are many dark-skinned, Indian-looking Filipinos in Cainta?

The Indians introduced curry dishes, which were later sold in native food shops near the Pasig River. These food stalls proliferated at an astounding rate, with people calling them carinderia by the first half of the 1800s–in the same way they used pansiteria to refer to Chinese eateries serving pansit, or panaderia for those that sold pan (bread).

A variant of carinderia is the karihan. It followed the trend which popularized the word tindahan, from the Spanish root word tienda, meaning “store or place where things are sold.”

What are Jose Rizal’s favorite foods?

Our national hero was not a picky eater. He’s a simple fellow who craved home-cooked meals, usually with a cup of rice, hot chocolate, and sardinas secas—or simply tuyo—for breakfast, as discovered by historian Ambeth Ocampo.

Valentina Sanchez or “Aling Vale,” a cook who once served in the Rizal family kitchen, remembered that his favorite childhood food was carneng asada (beefsteak with sauce). While studying in Madrid, Pepe asked that his family bring him some bagoong, as well as guava, tamarind, and mango jellies.

Equally fascinating were the personal stories by two cooks who worked for Rizal during different periods of his adult life. Asing, a Chinese cook who served the Rizal family while they’re living in Hong Kong, attested that his boss was not finicky when it comes to food: “He ate everything, but was very temperate. He ate both rice and bread.”

Also Read: 36 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

Faustino “Tinong” Alfong, on the other hand, cooked for Rizal in Dapitan. The Cebuano native shared that his employer fancied three kinds of food for his meals: “something native like brothy sinigang; a Spanish viand; and a mestizo dish.”

Other notable food Rizal enjoyed while in exile were pancit luglog cooked by his sister, Narcisa; and the chili miso sauce made by his sweetheart, Josephine Bracken.

References

Aguilar, F. (2005). Rice in the Filipino Diet and Culture (1st ed.). Makati City, Philippines: Philippine institute for Development Studies.

Cruz, I. (2003). The fork and spoon. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A14. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/x606ut

Daily Kentucky New Era,. (1914). Good Manners for Savages. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/M27qtk

Fernandez, D. (1988). Culture Ingested: Notes on the Indigenization of Philippine Food. Philippine Studies, 36(2). Retrieved from http://goo.gl/hILGzm

Fernandez, D. (1994). Tikim: Essays On Philippine Food And Culture. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Fernandez, D. (2000). Palayok: Philippine food through time, on site, in the pot. Bookmark.

Ocampo, A. (2012). Rizal Without The Overcoat. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Schenectady Gazette,. (1986). Usage of Eating Utensils Traced Through History by Researcher, p. 17. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/Kh53vs

Sta. Maria, F. (2002). Knights of ‘adobo,’ or the medieval connection in a favorite Filipino dish.Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. D4. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/p7fhRD

Sta. Maria, F. (2006). The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Sta. Maria, F. (2012). The Foods of Jose Rizal. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Tayag, C. (2012). ‘Sawsawan’: Dip it good. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 13 December 2015, from http://goo.gl/S2wqZv

Written by FilipiKnow

in Facts & Figures, Food & Health, History & Culture, Juander Why

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net