29 Things You’ll Never See in Manila Again (Part II)

If you don’t know where you came from, you can never know where you’re supposed to go. This is why it’s essential for Filipinos to know our country’s history, the things it has lost through the years, and those that still remain and should be preserved.

Also Read: 20 Beautiful Old Manila Buildings That No Longer Exist

In Manila, for instance, countless landmarks that once decorated the city are now gone forever. Still, their memories remain a good source of endless fascination and nostalgia. Let’s take a look back on some of the things that we’ll probably never see in Manila again.

11. Casa Hacienda.

Casa Hacienda refers to a one-and-a-half story building which stood in a 2,881 square meters of land in Makati owned by the Ayalas. The wood-concrete hybrid structure initially served as the office of Ayala y Compañía (modern-day Ayala Corporation). Later, it also served as a warehouse, a poultry house, a hat factory, an extension of Makati Fire Station, and even a dorm for displaced Jolo students.

In the end, the property was donated to the local government, and later turned into a plaza and children’s playground as part of First Lady Imelda Marcos‘ beautification program. Today, the former location of Casa Hacienda is occupied by the Poblacion Park, located along the Pasig River and right across the Museo ng Makati.

12. Rosie’s Diner.

Before Ermita became notorious for its nightclubs and KTV bars, there were wholesome restaurants like Rosie’s Diner which offered classic American food to its loyal customers.

Located at M.H. Del Pilar St., Rosie’s Diner was where students and families would usually stop by if they wanted to satisfy their cravings for American diner foods. The place became famous for its signature Midget Burgers (six small burgers decorated with small flags), taco salad, and creamy milkshakes. Other mouth-watering dishes on their menu include roast beef sandwich, apple pie ala mode, chicken pie, banana split, and Hawaiian pizza.

When the Ermita restaurant was no longer profitable, Rosie’s Diner moved to Pampanga in the early 1990’s. The defunct Ermita branch was later renamed L.A. Cafe.

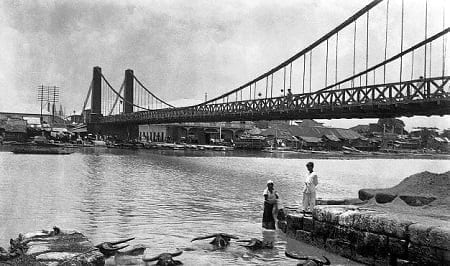

13. Puente Colgante.

Completed in 1852, the Puente Colgante–which spanned the Pasig River and connected Quiapo to Ermita–was originally named Puente de Claveria, in honor of the famous governor-general who ordered the Filipinos to take Spanish surnames. This suspension bridge was made primarily of wood as opposed to the common misconception that it was made entirely of steel.

Construction of the bridge was started in 1849 by Ynchausti y Compania (also known as Ynchausti y Cia, owned by Jose Joaquin de Ynchausti). After its completion, the corporation operated it as a toll bridge for 90 years, thanks to the city government of Manila who awarded them the franchise. However, city officials bought the bridge from the company on June 9, 1911 for 42,500 pesos, and the tolls were then abolished several days later.

Also Read: 6 Scary Bridges in the Philippines You’ll Have To See To Believe

Measuring 360 ft. long and 23 ft. wide, the bridge had served horse- and carabao-drawn carriages as well as thousands of pedestrians for many years until it was finally replaced by the modern-day Quezon Bridge in 1938. And contrary to popular belief, it was a Basque engineer named Matias Mechacatorre (not Alexandre Gustave Eiffel) who was commissioned by Ynchausti y Cia to design Puente Colgante.

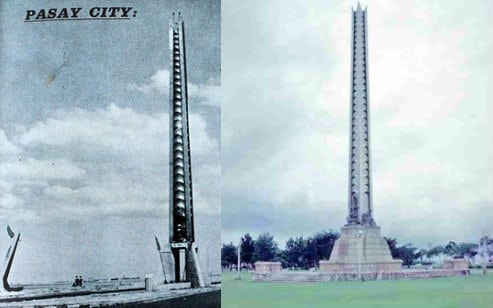

14. The Welcome Mat/Rizal Monument’s Controversial Steel Shaft.

Years before the centennial of Dr. Jose Rizal’s birth in 1961, there were already plans to build a cultural complex named after the national hero. The project–consisting of a national theater, museum, and library–was undertaken by the Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission (JRNCC). However, the construction of such modern buildings would also mean that the Rizal monument (which was the centerpiece of the complex) would be a little out of place, no thanks to its small size and crude design.

Fortunately, famed architect Juan Nakpil came to the rescue, armed with an idea to superimpose a shaft made of steel and aluminum over the granite obelisk. Several design proposals were submitted, but the final approval went to a modest pylon that would not bring drastic change to the original Rizal monument. With a cost of 145,000 pesos, the shaft increased the monument’s height from 12.7 meters to a whopping 30.5 meters.

Also Read: 25 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

Installed nearly overnight, the vertical pylon caused a public uproar, with critics saying that it dwarfed the Rizal figure and going as far as describing it as “carnivalistic,” “nightmarish,” “fintailed monstrosity,” and “like a futuristic rocket ship about to take off for interstellar space.” The controversial shaft was removed two years later upon the request of Secretary of Education Alejandro Roces and Director of Public Libraries Carlos Quirino. It had served as a welcome monument at the Pasay-Parañaque boundary along Roxas Boulevard before it was dismantled and disappeared for good.

15. Harabas Taxicab.

General Motor’s Harabas taxi is the precursor of today’s FX taxis. It entered the market at a time when there was still a Philippine car manufacturing program.

In 1973, the country implemented the Progressive Car Manufacturing Program (PCMP). It took effect in the Philippines nine years earlier than Malaysia and paved the way for innovation in the local automotive industry.

One by one, companies produced a new generation of utility vehicles–known as Asian Utility Vehicles (AUVs)–that was poised to compete with the jeepneys. The vehicles that came out of this era were Ford Fierra, Toyota’s Tamaraw, Francisco Motors Corporation’s Pinoy and Harabas. The AUVs emerged as air-conditioned passenger vans with four swing doors at the sides and one at the back.

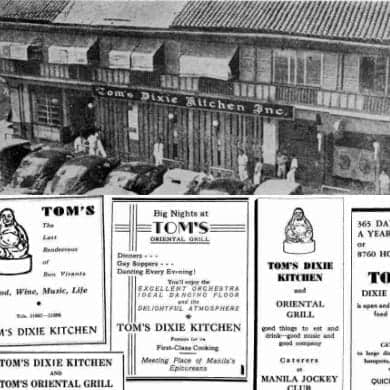

16. Tom’s Dixie Kitchen.

Tom’s Dixie Kitchen was a Manila restaurant that ruled the 1930’s for three reasons: it served arguably the best Southern-style American dishes in the city, it was frequented by some of Manila’s elites, and it opened day and night.

Located in Plaza Goiti (now Plaza Lacson) in Santa Cruz, Tom’s Dixie Kitchen was owned and operated by Tom Pritchard, one of the black American soldiers who chose to settle in the Philippines after participating in the Spanish-American War. After his stint in the Army, Pritchard worked at Clarke’s Ice Cream Parlor as a chef. He then started his own cafe where he helped prepare and serve Southern-style American dishes. Soon, the restaurant in Plaza Goiti grew by leaps and bounds, allowing Pritchard to open Tom’s Oriental Grill which featured an orchestra and upscale dinners.

Also Read: 5 Awesome Philippine Heroes Who Are Not Filipinos

Tom’s Dixie Kitchen was a hit among its high-income customers ranging from bankers and businessmen to celebrities and government officials (including the late President Manuel L. Quezon). People often visited the place at night after watching concerts or enjoying jai alai or cockfights. Some of the restaurant’s specialties include ham and eggs, hot dogs, southern fried chicken, chili con carne, and roast beef sandwiches among others.

17. Binondo Lift Bridge.

Measuring 15 meters long, the Binondo Lift Bridge was only one of its kind in the country. It’s categorized as a draw or lift bridge which means in addition to allowing pedestrians to travel from one end of Plaza Cervantes to Calle Soledad, the structure was also capable of lifting its platform to as high as 4 to 5 meters above the water line to accommodate the cascos plying the Estero de Binondo.

Inaugurated in 1913, the innovative electrically-driven bridge was built by a German-owned company. It served an important role of bringing in goods from the docks at Pasig River to the various commercial establishments in Binondo. Although it survived the war, the Binondo Lift Bridge was demolished in the early 1980s and replaced by a standard concrete bridge.

18. Tivoli Movie Theater.

An incredible Art Deco structure of pre-war Manila, the Tivoli was one of the movie theaters built along Plaza Santa Cruz, the other one being the Savoy or Astor.

On January 4, 1933, Ang Aswang, the first “talking” film in the history of Philippine cinema was released in Tivoli. Its sound was produced by an audiographer named William Smith at the Manila Talkatone Studio in Pandacan. The film was also released three days earlier in Lyric Theater.

Tivoli might have been ravaged by war or gradually destroyed due to neglect. It was later replaced by Cine Sta. Cruz.

19. New Europe Restaurant.

Owned by Heinz Wielke, the New Europe Restaurant was one of the fancy restaurants that once populated Isaac Peral Street (now U.N. Avenue).

Dubbed as “the house of good food,” the New Europe was fully air-conditioned to provide comfort to its customers. Along with the Swiss Inn (also in Isaac Peral), New Europe was often the restaurant of choice of members of alta sociedad looking for premium burgers or expensive European dishes.

20. The Quad.

If you lived in Makati City in the ’60s or ’70s, then you probably remember The Quad–the place to be if you wanted to watch a good movie with your family.

The Quad comprised of four cinemas. Its basement was once home to video game arcades, probably the first in the city. Using only their one-peso coins, kids would enjoy playing various attractions ranging from pinball machines to air hockey. At the back of the Quad, on the other hand, was the Glorietta, then only known as a park where outdoor concerts or mass would be held and where people would often rest in between their visits in various retail shops around the area.

In the 1990s, both the Quad and the Glorietta Park were both given a face-lift by the Ayala Land Corporation to give way to the modern-day Glorietta Mall.

Also Read:

29 Things You’ll Never See in Manila Again (Part I)

29 Things You’ll Never See in Manila Again (Part III)

References

Alcazaren, P. (2011). The unbuilt Jose Rizal Cultural Center. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 13 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/BZ77qf

De La Torre, V. (1981). Landmarks of Manila 1571-1930 (p. 56). Makati: Filipinas Foundation, Inc.

Del Castillo-Noche, M. (2006). Bridge Over Not So Troubled Waters: Spanning Communities and Building Relationships. Icomos Philippines. Retrieved 13 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/zYDWck

Gopal, L. (2012). Santa Cruz. Manila Nostalgia. Retrieved 13 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/n7s0mG

Gopal, L. (2013). Puente de Colgante. Manila Nostalgia. Retrieved 12 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/5nntXI

Lo, R. (2014). The many ‘firsts’ in Phl cinema. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 13 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/EcNang

MakatiCity.com,. Glorietta Mall. Retrieved 13 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/W0bJfm

Manila and the Philippines.

Moore, C. (2007). Fighting for America: Black Soldiers-the Unsung Heroes of World War II (p. 43). Random House Publishing Group.

Prudente Sta. Maria, F. (2006). The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935 (p. 180). Mandaluyong City: Anvil Publishing Inc.

Roces, A. (2009). The hanging bridge of Manila County. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 12 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/X7TiKm

Vorpal, J. (2013). 10 Places in Manila that Evoke Childhood Nostalgia. Smart Parenting. Retrieved 12 April 2015, from http://goo.gl/e2KifT

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net