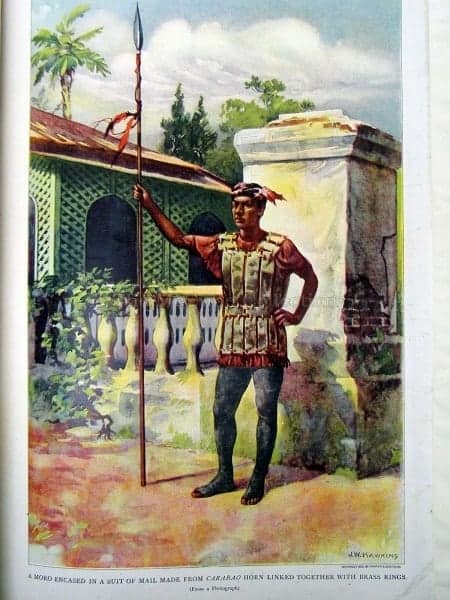

Early Filipino warriors used drugs to enhance their killing capabilities (or did they?)

Drug use in the Philippines is quite older than you think. That is if we’re going to believe what’s written in Blair and Robertson’s The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803.

In 1631, more than a century after Magellan supposedly discovered the Philippines, Diego de Bobadilla told the story of another conquistador, Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa, who set sail for the islands to explore its untapped resources.

This time, however, the explorer had set his sights only on Mindanao, the land of the ferocious “Mohameddans.”

Don Esteban knew the risk when he sealed the deal with the Spanish king. As promised to his Majesty, he would conquer Mindanao at his own expense, but in exchange, the Majesty would award him “as tributary vassals, ten thousand of the first Mindanaos whom he should subdue and choose for himself, and granting him other favors which he sought.”

Also Read: How Spain “Almost” Abandoned Philippines in 1765

When everything was agreed upon, Don Esteban, with the title of governor and captain-general, led his army of four hundred Spaniards as well as over four thousand natives towards Mindanao. Embarking in a fleet of Visayan warships called karakoa and the larger juanga, they sailed from Oton island in the present-day Iloilo to their destination in Mindanao.

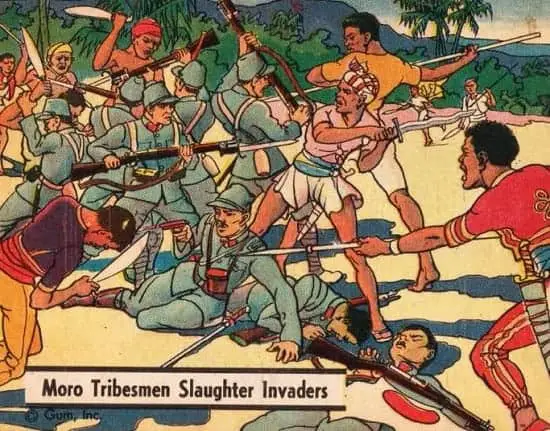

The Moros reportedly fled after seeing the overwhelming number of conquerors approaching their land. For a while, the Spaniards thought that things were working in their favor. But boy were they wrong.

While Don Esteban was marching with his men in some unfamiliar territory, a furious Moro jumped out of the bush and struck the general with a kampilan (a single-edged long sword). It was said that the assassin hit Don Esteban so hard “that it cleft his skull from ear to ear.” The Moro was mauled and died on the spot.

In retrospect, what the Moro did was an act of self-sacrifice. He knew the fate waiting for him, but he did it anyway with almost the same bravery as the modern-day suicide bombers. But the chronicler had an intriguing explanation: The assassin was allegedly high on opium, a powerful narcotic drug that the Moros intoxicated themselves with before engaging in a war or suicidal attack.

Also Read: Meet the Terrifying Moro Warriors and Heroes of WWII

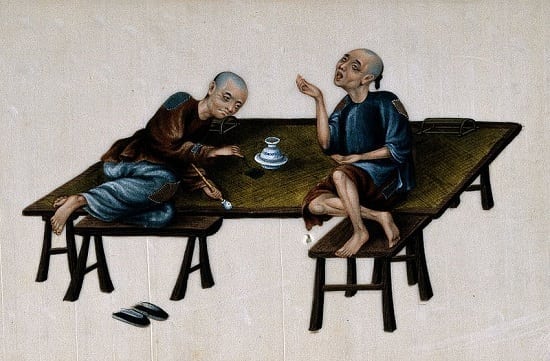

Opium is a psychoactive drug as old as the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations. The drug itself is obtained from the milky latex that comes out of the seed capsules of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum). You can then turn the substance into powder, or extract such derivatives like heroin, codeine, and morphine.

Before this discussion turns into a medical mumbo-jumbo, let me simplify opium by mentioning three of its most powerful effects: suppression of pain, a state of euphoria, and other physiological effects that almost always lead to addiction.

Related Article: The Filipino Doctor Who Helped Discover Erythromycin (But Never Got Paid For It)

How did opium reach the Philippines?

For the record, our pre-colonial ancestors are known to have no access to intoxicants other than native alcoholic beverages and masticatory preparations made of betel leaf (“buyo”), areca nut (“bunga”) or lime (“hapug”). At the dawn of the 17th century, both the British East India Company and the competing Dutch East India Company were established. The two introduced opium to the Asian market, including the Philippines.

In his paper for the Philippine Sociological Review, Professor Ricardo Zarco of University of the Philippines explains that the opium may have originated from two sources: “from the British into China and from there into Manila through Chinese merchants who frequented its ports; and from the Dutch through southern Philippine waters.”

READ: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

By the 18th century, Augustinian historian Antonio Mozo discovered that early Visayan and Mindanaoan warriors didn’t exclusively use opium to get high. For instance, a root crop, known in Kapampangan as “sugapa,” could provide even the meekest warrior with the reckless courage needed in war.

As reported by Mozo, “he who eats it is made beside himself, and rendered so furious that while its effect lasts he cares not for dangers, nor even hesitates to rush into the midst of pikes and swords.”

He added that “by eating it at the time of the attack, they enter the battle like furious wild beasts, without turning back even when their force is cut to pieces; on the other hand, even when one of them is pierced from side to side with a lance, he will raise himself by that very lance in order to strike at him who had pierced him.”

History of drugs in warfare, in a nutshell.

Using psychoactive substances, or being addicted to them, is nothing new in the history of war. According to Polish historian Lukasz Kamienski, in his book “Shooting Up: A History of Drugs in Warfare,” drugs have been used numerous times in history to transform humans who would have otherwise struggled to endure war into merciless killing machines.

From the Viking warriors who allegedly drank Amanita mushrooms to the German soldiers who used Pervitin to fight stress during the Poland invasion of 1939, history never runs out of stories that prove drugs have long been used–and most likely abused–in warfare.

The never-ending war.

Going back to the Philippines, opium addiction within the Filipino society culminated in the latter part of the 18th century and throughout the early years of the succeeding century. Com. Charles Wilkes, one of the first few Americans to ever set foot in Jolo, observed that opium was no longer being used to brave out wars, but as a recreational drug that most likely spiraled the Moro people into addiction.

In his five-volume work entitled “Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842,” Wilkes recalls one visit with Sulu Sultan Mohamed Damaliel Kisand: “…whose eyes were bloodshot and seemed to consume large quantities of opium…his son Datu Mohamed Polalu, constantly under the effect of opium.”

Also Read: 25 Things You Didn’t Know About President Rodrigo Duterte

As the years passed by, Filipinos’ preference for drugs has evolved as well. By the 1950s, some users started favoring morphine injections over opium as the former provides a different level of privacy one could not enjoy by smoking opium. Coca leaves and marijuana first became popular in the 1940s and the 1950s, respectively, and have since enslaved many Filipinos who can’t seem to escape the mighty grip of drug addiction.

With the present administration engaged in an unprecedented war against drug addiction, it’s high time to reflect on how far we’ve come since our opium-smoking ancestors first used drugs in warfare. Today’s battle has taken on a different context, and drugs are now being used by some as an excuse to take the law into their hands.

So, who’s more savage now?

References

Blair, E. & Robertson, J. (1909). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803; explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century (Volume XXIX) (pp. 90-92).

Opium. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 August 2016, from https://goo.gl/4XUsff

Rickett, O. (2016). Soldiers Have Used Drugs to Enhance Their Killing Capabilities in Basically Every War. Vice.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016, from http://goo.gl/XWGeAJ

Ugarte, E. (2000). “The Dissension of Other Things”: The Disparity Between The Spanish and American Perceptions of Amok. Asian Studies, 36(1), 64. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/BZt9uI

Zarco, R. (1995). A Short History of Narcotic Drug Addiction in the Philippines, 1521-1959. Philippine Sociological Review, 43(1-4), 1-15. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/sTUZDx

Written by FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net