10 Little-Known Facts About The Katipunan

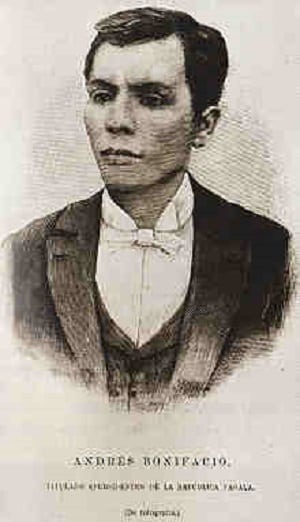

We know it as that shadowy group created by Andres Bonifacio to liberate the country from Spain. But aside from that, is there anything else we would want to know about the Katipunan?

Also Read: 7 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Andres Bonifacio

Yes, since the Katipunan is arguably one of the most influential groups to have ever shaped Philippine history. It rightfully deserves recognition and what better way to give that than to learn about some little-known facts and events connected to it.

1. It Had A “Secret Chamber” That Punished Its Members.

While well-known is the fact that the KKK operated like a shadow government with its legislative and executive functions, its judicial branch is a little more obscure.

According to historians, the Katipunan had a council called the Camara Secreta (Secret Chamber) composed of Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, and Dr. Pio Valenzuela. Also called the Camara Negra (Black Chamber) and Camara Reina (Supreme Chamber), this sinister-sounding body doled out punishment to members who betrayed or broke the by-laws of the Katipunan.

Related Article: How A Two-Peso Salary Increase Led To The Discovery of Philippines’ Secret Society

Death sentences were usually handed down in the form of a cup with a serpent curled around it. Supposedly, five Katipuneros met their ignominious end inside the dreaded chamber.

2. It Actually Organized The First Ever Republic.

Notwithstanding the heated debate of whether it became a de facto government after it operated in the open, the Katipunan actually succeeded in establishing a republic long before Emilio Aguinaldo’s Biak-na-Bato or the Malolos Republic.

Located in Bulacan, the Republic of Real de Kakarong de Sili was established on December 4, 1896, by some 6,000 Katipuneros led by Supreme Chief Canuto Villanueva and General Eusebio “Maestrong Sebio” Roque. Together they constructed a fort in the area and established a working mini-state.

The republic operated like a real government, complete with its own armed forces, police, and other civilian offices. Unfortunately, the republic lasted for only a month. On January 1, 1897, a large Spanish contingent overran the fort and massacred an estimated 1,000 – 3,000 Katipuneros. The most famous survivor of this setback would be none other than Gregorio del Pilar.

A lieutenant at the time, del Pilar sustained injuries during the battle—his baptism of fire—but managed to escape. Today a monument—the Inang Filipina Shrine—stands on the site as a testimony to the bravery of the revolutionaries.

3. The Real Meaning Of The Letter K.

Out of all the letters we have in the alphabet, none stand so popular—controversial—as the letter “K,” and for good reason. The letter has become a fixture among militant groups, mutineers, and other so-called modern revolutionaries—which lead us to wonder why it is so popular in the first place.

Out of all the letters we have in the alphabet, none stand so popular—controversial—as the letter “K,” and for good reason. The letter has become a fixture among militant groups, mutineers, and other so-called modern revolutionaries—which lead us to wonder why it is so popular in the first place.

The answer, of course, lies in the era before the formation of the Katipunan, when debates were still raging over the creation of a new orthography. Filipino nationalists—Jose Rizal included—at the time favored replacing the letter “C” found in the Spanish-influenced Tagalog alphabet with the letter “K” since it had already been in use since during the period of the pre-colonial Filipinos.

Also Read: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

In time, Andres Bonifacio—a member of Rizal’s La Liga Filipina—came to wholeheartedly adopt the letter and its revolutionary undertones. For him and many revolutionaries, the letter would come to symbolize independence and liberty. Long story short, the CCC became KKK instead.

4. The KKK Had Three Supremos.

One common misconception among many Filipinos is that Andres Bonifacio had always been the supreme leader of the Katipunan since its inception. However, Bonifacio was only the third Supremo, having been elected to the position three times, first on January 1895, the second on December 31 of that same year, and the third and last time on August 1896.

The first Supremo was Deodato Arellano—a Katipunan co-founder—who was elected in 1892. However, his ineffectiveness caused Bonifacio to depose him and order another round of elections on February 1893 which resulted in Roman Basa becoming Supremo.

Related Article: 7 Reasons Why Filipinos Hate Emilio Aguinaldo

Bonifacio also deposed Basa in 1895 after the latter criticized him over the recruitment process and his handling of the organization’s funds. After Bonifacio, no other man (not even Aguinaldo) ever claimed the title.

5. It Already Had A National Anthem.

Trending Now: 12 Rare Pinoy Historical Videos You’ve Probably Never Seen

With Bonifacio’s death, however, Nakpil’s work was overlooked by Emilio Aguinaldo in favor of that of Felipe. Incidentally, both men were province mates. Nakpil later renamed his piece to Salve Patria as a tribute to Jose Rizal. Although the original scores were later lost during World War II, the current version—which Nakpil reconstructed from memory in his old age—is still alive and well today.

6. The Aims Of The Katipunan After The Revolution.

Thanks in part to the political rivalry between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo, we can only speculate what would have happened had the Katipunan remained a united front and succeeded in expelling the Spanish from the archipelago.

Although it is generally held that the Katipunan’s aim was to completely break away from Spain and create a new government, not much is really known what kind of government Bonifacio would’ve wanted to establish aside from it being obviously patriotic and anti-colonial by nature. The issue is a matter of debate for historians up to now, with some inferring from Bonifacio’s writings that he wanted a “communist republic.”

However, other historians have dismissed that view due to a lack of actual evidence. According to them, Bonifacio’s wish to create a government and society which viewed and treated men as equals did not mean he was an outright communist. Rather, Bonifacio’s views came as a natural reaction to centuries of Spanish oppression.

READ: The Lottery Winner Who Changed Philippine History

7. It Lost Much-Needed Support After The Rizal Meeting.

We all already know how the Katipunan respected Rizal’s advice so much they sent Pio Valenzuela to Dapitan in order to secure his blessing for an armed revolution. However, instead of saying yes, Rizal denounced their plan as premature and instead urged them to gather more material support from the wealthy Filipinos if they wanted to really win.

Bonifacio—disappointed by Rizal’s hesitation to support the Revolution—was said to have called him a coward and ordered Valenzuela to keep silent on the matter lest it affects the morale of their men. However, Valenzuela was reportedly compelled to reveal the details of his meeting with Rizal by the top leaders of the Katipunan.

READ: 10 Insane ‘What If’ Scenarios That Almost Changed Philippine History

Upon hearing the news of Rizal’s refusal to endorse an armed uprising, many of the wealthier supporters of the Katipunan withdrew their pledges of support to the movement. Not only that, a good number of rank-and-file members lost heart and turned in their membership. Valenzuela’s disclosure of Rizal’s refusal also caused a rift between him and Bonifacio.

8. It Tried To Get Japan’s Help.

The Katipunan, in its bid to secure support for the revolution, also looked to Japan as a source of potential aid.

At the time, Japan had been a shining example of defiance against Western influence and the Katipuneros hoped that the Japanese would also help them fight off the Spanish. In fact, the Katipunan’s Big Three along with Daniel Tirona and interpreter Tagawa “Jose” Moritaro secretly met with the captain of a Japanese warship and the Japanese consul at a bazaar in Manila on May 1896.

Did you know? The Japanese had been planning to take over the Philippines for centuries.

During their meeting, the Katipunan handed to the captain their letter to the Japanese emperor asking for the Japanese people’s help to liberate the Philippines. Although the end of the meeting saw the Japanese agreeing to sell the Filipinos much-needed arms and ammunition, the deal never transpired due to a lack of funds and because the revolution broke out prematurely. Also, Jose Dizon, the man tasked to secure the weapons from Japan, was one of those arrested early on.

9. The Bonifacio Plan.

Another misconception that needs to be dispelled is the notion that Bonifacio was a terrible strategist. On the contrary, he actually planned to take Intramuros—then the seat of the Spanish government—in order to take out their leadership in a decapitation strike and while most of their forces were still stationed in Mindanao.

As fate would have it, the plan failed as the rebels from Cavite did not join the battle. According to them, Bonifacio failed to raise the signal for them to march to Intramuros. Many variations of the signal in question have been put forth including fireworks, cannon fire, balloons, and even a blackout in Bagumbayan.

However, many historians have also questioned that theory on the basis of its impracticality. Since Cavite is relatively far off from Manila, the rebels waiting for the signal would have inevitably arrived late for the battle. Also, the Cavite leaders had already earlier expressed their reservations about joining the offensive due to a lack of weapons.

As a result, it’s anybody’s guess as to whether the revolution would have ended early in the Filipinos’ favor had the Caviteños bothered to show up.

10. The Little-Known Revolts In Mindanao.

So much attention has been focused on the revolution in Luzon and in the Visayas that we have forgotten Mindanao had also been turned into a battlefield during that period. Specifically, the “Calaganan Mutiny” and the establishment of the Republic of Zamboanga prove the fight for freedom was a national endeavor.

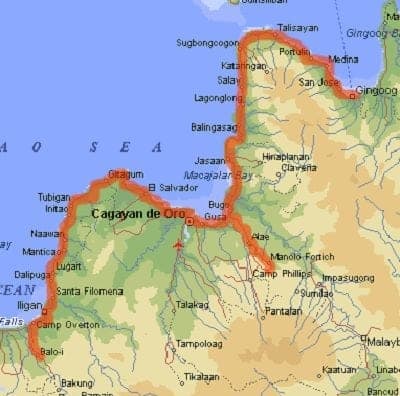

Regarding the mutiny, it was said to have started a month after full-blown hostilities broke out in Luzon. The mutineers—reported to be conscripted, KKK deportees from Luzon, lumads and Moros—initiated a revolt in Lanao del Norte which then spread to the neighboring areas including Bukidnon and Cagayan.

Also Read: 10 Most Infamous Traitors in Philippine History

Spanish forces had to be reinforced with a gunboat before they could finally quell the revolt. Today, many from that region are petitioning to include Mindanao as the ninth ray in the Philippine flag as recognition of the patriotism of the local revolutionaries.

The Republic of Zamboanga, on the other hand, was formally established on May 18, 1899, after the Spaniards surrendered and evacuated the city. It even continued to exist for another four years before the Americans finally dissolved it.

References

Agoncillo, T. (1990). History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc., p.158.

Baños, R. (2005). What NHI should have done instead for Iligan. [online] Heritage Conservation Advocates. Available at: http://goo.gl/uXwTG8 [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Chua, M. (2012). UNDRESS BONIFACIO, Ang Pagsalakay ni Bonifacio sa Maynila. [online] It’s XiaoTime!. Available at: http://goo.gl/I9YVcQ [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Cruz-Araneta, G. (2013). Katipunan decoded. [online] Manila Bulletin. Available at: http://goo.gl/hrml6T [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Palatino, R. (n.d.). KKK for Revolution. [online] MongPalatino.com. Available at: http://goo.gl/FpJYm8 [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Presidential Museum and Library, (2013). The Founding of Katipunan. [online] Available at: http://goo.gl/BMNW1p [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

The Kahimyang Project, (2011). Dr. Jose Rizal in Dapitan and the Katipunan. [online] Available at: http://goo.gl/4jOUGz [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Watawat.net, (n.d.). The Republic of Real de Kakarong de Sili. [online] Available at: http://goo.gl/fil3Xo [Accessed 26 Nov. 2014].

Philippine History by M.C. Halili

Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation by Christi-Anne Castro

Manila during the revolutionary period by Gregorio F. Zaide

The Katipunan; or, The Rise and Fall of the Filipino Commune by Francis St. Clair

The First Filipino by Leon Ma. Guerrero

Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-colonial Imagination by Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson

Struggle for Freedom 2008 Edition by C. Duka

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net