13 Filipino Expressions With Crazy Origins You Would Never Have Guessed

We’ve heard them uttered by our old folks when they chatted with friends and swapped chismis.

These are the Filipino expressions and lines that they laced their conversations with–familiar to the ears, but alien to some of us in meanings.

Most of them make hazy references to historical figures, plants, sports, and places—but why? This article explores the fascinating backgrounds behind such colorful expressions.

Also Read: 11 Filipino Slang Words With Surprising Origins

1. “Tapos na ang boksing!”

“Di man nakapasok si Miss Philippines sa Top 10. Tapos na ang boksing!”

Meaning: It is finished. It is doomed and it’s done.

Origin: During the Japanese Occupation, “tapos na ang boksing” was a favorite expression of teenagers. Boxing was a sport promoted and encouraged by Americans in the 1920s. So, for pro-Japanese elements, the expression meant that America was finished and that MacArthur would never return to the Philippines. But for those who continued to believe in America’s promise, they used the phrase to denote that Japan would ultimately fall.

Related Article: Thrilling Facts You Didn’t Know About ‘Thrilla in Manila’

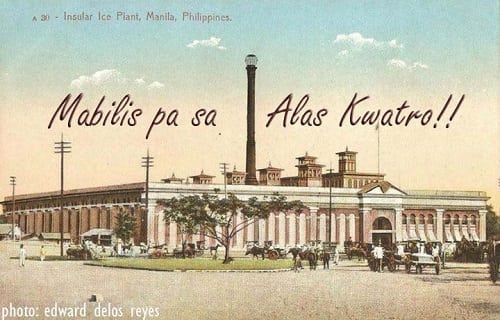

2. “Mabilis pa sa alas kwatro.”

“Nang dumating yung kulektor ng utang, naglaho si Andong—mabilis pa sa alas kwatro!”

Meaning: To leave in a mad rush.

Origin: In Lawton, at the foot of the Quezon Bridge, once stood the imposing Insular Ice Plant with its 10-floor chimney. It was equipped with a loud siren that was sounded off three times in a day to indicate the start of work at 7 a.m, lunch break at 12 noon, and dismissal of workers at 4 p.m.

READ: 20 Beautiful Old Manila Buildings That No Longer Exist

At the last siren signal, Insular workers would prepare for home by heading towards the exit gates, where they fell in line to log out. There was so much anticipation for the dismissal time that workers dashed out in a rush to be at the head of the line first—faster than the 4 pm. siren.

3. “Agua de Pataranta.”

“Happy hour na…ilabas na ang Agua de Pataranta!”

Meaning: Euphemism for hard liquor.

Origin: Medicinal waters sold by boticas and pharmacists in the ‘20’s and ‘30’s still carried Spanish brand names. For example, Botica Boie listed in its stock water-based remedies like Agua Fenicada (phenol water) Agua de Botot ( a mouth rinse), Agua Boricada (boric acid solution for the eyes) and Agua de Carabaña (mineral water).

A drinking man’s bottle was disguised as medicine too—Agua de Pataranta—liquor strong enough to addle his brains and put him in a confused stupor—or “taranta.”

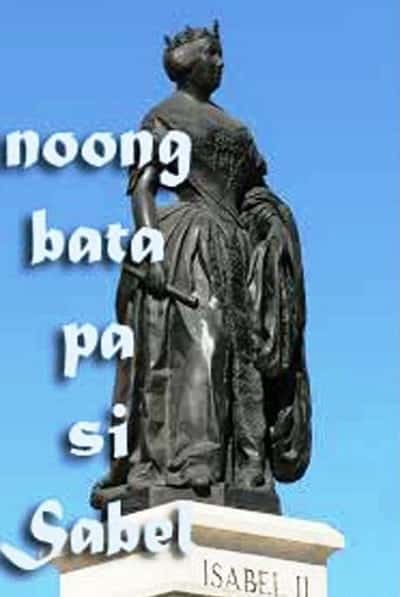

4. “Noong bata pa si Sabel.”

“Uso na yang sayaw na ‘yan–noong bata pa si Sabel!”

Meaning: A descriptor for something that has been in existence or in practice a long time ago.

Origin: This expression pays tribute to Queen Isabella II of Spain, who reigned from 1843 to 1868. “Noong bata pa si Sabel” literally means “when Isabel was but a child,” hence when the world was younger.

Queen Isabel’s term was rocked with internal palace intrigues, influence-peddling, and conspiracies, which ended with her exile and abdication. Queen Isabel’s profile appeared in local 1860’s coins; her bronze statue stands on Liwasang Bonifacio.

Interestingly, the late National Artist, Alejandro Roces contends that Isabel’s enemies referred to her as “la perra” (the bitch), hence the coins that carried her profile became known as “perra” or “pera,” a term used today for all forms of money.

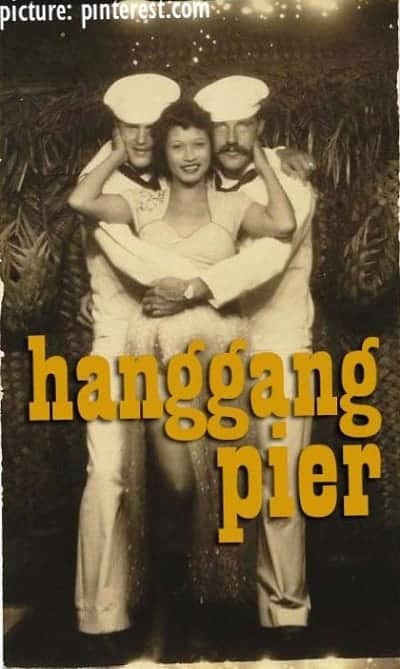

5. “Hanggang Pier.”

“Hanggang pier na lang ang love story ni Inday at James!”

Meaning: To be left behind with an unkept promise.

Origin: The assignment of American military servicemen in Clark, Subic and Sangley Point beginning in the 1900s spawned the beginnings of our entertainment industry that included food, drinks, dancing and later, of course—damsels!

Thru the ’30’s-’60’s, relationships were formed by Americans on furlough with local girls—many from the bars and dancing halls. Some affairs were for real, but still, hundreds of others ended at the departure area—hanggang pier.

Also Read: The 8 Most Haunting ‘Abandoned’ Places in the Philippines

Thus, the expression has come to mean that a person would not keep his promise, or that a Pinay had been left behind by a Kano, often with a Fil-Am baby souvenir—at the pier.

6. “Natutulog sa pansitan.”

“Iiwanan ka ng panahon kung lagi kang natutulog sa pansitan!”

Meaning: Failure to grab an opportunity because of laziness.

Origin: Pansit-pansitan (Shiny bush, Peperomia pellucida Linn) is a very common herb that grows quickly in cool, damp places—carpeting nooks and yards with their soft, fleshy leaves.

Also Read: Rafflesia – Giant flower that smells like corpse

Workers on the field often took a respite from their job and the harsh sun by napping on a patch of pansit-pansitan—hence, “natutulog sa pansitan.” Of course, it may have happened that a few took their naps longer, and this sleeping on the job can result in unfinished work—and lost opportunities.

7. “Nineteen kopong-kopong.”

“Yung damit na suot mo…parang sa panahon pa ng kopong-kopong!”

Meaning: Refers to a time so long ago, that nobody remembers anymore.

Origin: By the 1950s, the decade of the 1900s was considered a long time ago. When people wanted to refer to an event in the forgotten past, they reckoned that it happened sometime in the 1900s, hence “nineteen kopong-kopong.”

Related Article: 10 Shocking Old-Timey Practices Filipinos Still Do Today

“Kopong” is an Indonesian word that was also used in the Philippines, meaning “no content, empty”—thus, zilch or zero, as in 19 zero-zero!

8. “Lutong Makaw.”

“Lahat naman ng Olympic boxing finalists, puro Russians! Lutung-makaw!”

Meaning: A decision that has been rigged; a pre-arranged victory or success.

Origin: In the peacetime ’30’s, “makaw” (derived from Macau island, off the coast of Hong Kong), was an unofficial generic term used by Manilans for a Chinese immigrant, especially, cooks. Their culinary creations were called “lutong makaw”—cooked in Macau fashion.

Macau Chinese were known for their practice of pre-arranging their ingredients well in advance, even before a dish was ordered. A trademark dish was “pansit makaw,” always a bestseller along with pancit canton—which assured lasting ‘lutong makaw’ success every time it is served.

Another possible explanation could be traced back to Macau’s long gaming history that dates back for more than three centuries, earning the title “Monte Carlo of the Orient.”

In 1930, “Hou Heng Company” won the monopoly concession for operating casino games. Game-fixing was one of the hazards of the industry, including “cooking” (i.e. tampering) the outcome of the game even before it is played—hence “lutong-makaw.”

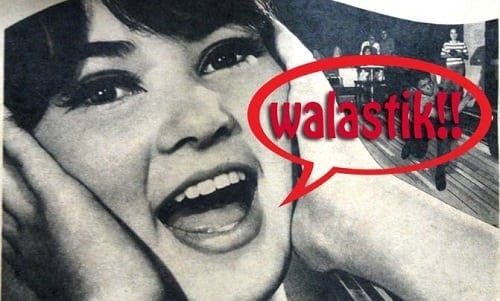

9. “Walastik!”

“Walastik! Ganda ng rubber shoes mo..Spartan ba iyan?”

Meaning: An effusive expression of praise when one notices something new and improved.

Origin: This very popular expression from the 1960s comes from the phrase “walang katigil-tigil” (unstoppable). This was contracted to “walastig,” and finally morphed to “Walastik!”

Thus, if somebody is seen wearing a new pair of shoes or pants, he will be greeted with “Walastik! Ang gara ng bihis natin…”—a compliment of his unstoppable improvement of style. “Walastik” was often paired with another expression, “Walandyo!” (“Walang Joe!”).

10. “Pupulutin sa kangkungan.”

“Huwag mong takbuhan ang responsibilidad mo,…kung hindi, pupulutin ka sa kangkungan!”

Meaning: Summary execution of a person who has committed an offense or crime without the benefit of a trial. Slang: to ‘salvage.’

Origin: A way of disposing of the bodies of people killed by summary execution is to hide it under a dense growth of kangkong (swamp cabbage). The semi-aquatic plant grows in profusion on swampy fields and on bodies of water like the Pasig River, where such victims’ cadavers are regularly fished out. Philippine media has popularized this expression in their reportage of “salvaging” cases.

READ: 30 Filipino Words With No English Equivalent

11. “Naghalo and balat sa tinalupan.”

“Huwag mong agawin ang girlfriend ko, kung ayaw mong maghalo ang balat sa tinalupan!”

Meaning: A free-for-all, a melee.

Origin: The literal translation—to mix up the peelings and the parings with whatever has been peeled or pared– does not make any sense to a Filipino who was brought up not to mix anything—even in the handling and preparation of fruits—or else, trouble will follow.

Also Read: 70 Things You Didn’t Know Had Filipino Names

Experience has taught him to always separate the skin from the fruit; for example, the thin skin of a siniguelas has to be meticulously peeled from the fruit if given to a child, as the skin can give indigestion if eaten. Pineapples have to be peeled a certain way, with all the “eyes” on the skin removed, which cause itchy throats. Even pomelos can taste too tarty if the sponge-like rind remains with the pulp.

So, it is wise advice never to mix the “balat sa tinalupan.”

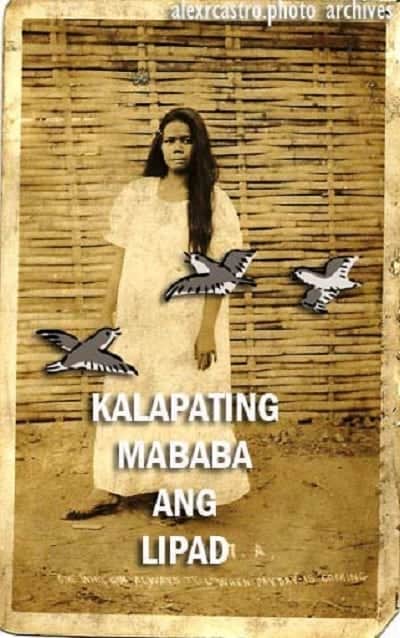

12. “Kalapating mababa ang lipad.”

“Tuwing gabi sa Makati, nagiging isa syang kalapating mababa ang lipad”

Meaning: A prostitute.

Origin: This popular euphemism for a “prostitute” has its beginnings in the backroom alley of Tondo, where existed a red-light district called “Palomar”— Spanish for a dovecot or a pigeon shed—existed with “palomas” proffering various leisure services.

READ: 100 English Words Commonly Mispronounced by Filipinos

During the American period, these women from Palomar would expand their trade to Sampaloc, along Gardenia St. (now Licerio Geronimo St.), where they were derisively labeled as low-flying, low-class birds—palomas de bajo vuelo.

13. “Matandang hukluban.”

“Pakialamera talaga ang biyenan ko. Palibhasa,matandang hukluban ‘yan!”

Meaning: A pejorative term for an old woman.

Origin: In Philippine mythology, Hukluban is a deity associated with death; her name is derived from the old Tagalog word “huklob” meaning enchantment.

READ: The Surprising Origin of “Cubao”

She was a shape-shifter, had the power to kill and heal, and was an attendant to the god of death, Sitan. She was depicted as an ugly, ancient, wrinkled crone. Thus, to be called a “matandang hukluban” means more than just old—you are an ill-mannered, scheming hag with evil intentions.

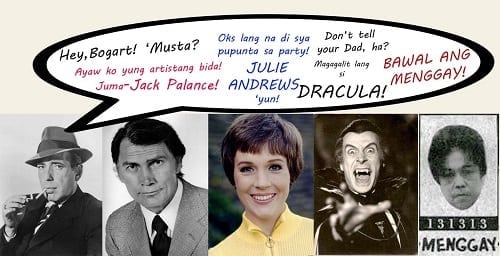

BONUS Trivia: Character Words

In the ’50’s and ’60’s, Pinoys used characters drawn from movies and the showbiz world as euphemistic terms to describe and define people. It is a practice that continues to this day.

Bogart or Bogat, a man or a dude, (after actor Humphrey Bogart, considered as the quintessential man’s man). Example: “Hey, Bogart! Kumusta na?”

Jack Palance, a person who over-acts, (after the kind of acting that actor Jack Palance is known for). Example: “Di bagay yung artista sa role nya, juma- Jack Palance!”

Julie Andrews, a demure woman, (as projected by the image of Julie Andrews in her films, “Sound of Music” and “Mary Poppins”). Example: “Hindi pupunta sa jam session si Clara…palibhasa, Julie Andrews!”

Dracula, an antagonist (e.g. a parent, a person of authority), after the horror madness of the 1950’s. Example: “Don’t tell you Dad about our party, Dracula ‘yun!”

Menggay, ugly, (after ’50’s comedienne Menggay). Example: “Nagkita kami ng dati kong classmate sa reunion..Menggay na sya!”

About the Author: Alex R. Castro is a retired advertising executive and is now a consultant and museum curator of the Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, Angeles City. He is the author of 2 local history books: “Scenes from a Bordertown & Other Views” and “Aro, Katimyas Da! A Memory Album of Titled Kapampangan Beauties 1908-2012”, a National Book Award finalist. He is a 2014 Most Outstanding Kapampangan Awardee in the field of Arts. For comments on this article, contact him at [email protected]

References

Alvina, C., & Sta. Maria, F. (1989). Halupi: Essays on Philippine Culture (pp. 48, 291). Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House.

Quirino, J. (1966). Jerky Jargon. Sunday Times Magazine.

Slang of the Times. (1963). Sunday Times Magazine, 30.

Other Readings: 11 Serious Answers To Mind-Blowing Pinoy Questions

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net