10 Incredibly Ironic Flaws You Can Find In Our Constitution

According to law experts, a constitution is more than just a piece of paper. It is the supreme law of the land, the manifestation of the people’s sovereignty. In other words, it contains the rights, rules, and obligations which the people and their respective governments have to follow and obey.

It is also generally held that there is no such thing as a perfect constitution, it being the creation of men. The same goes for our 1987 Constitution; unintentional mistakes, ambiguous or verbose sentences, lack of foresight, etc., have in one way or another besmirched what was supposed to be something revolutionary, resulting in massive unintended consequences which we ordinary Filipinos can feel up to now.

Also Read: 15 Weird Laws Filipinos Still Have To Live With

While this list won’t be pushing for Cha-Cha, it will point out the numerous flaws—both obvious and vague—one can find in our Constitution.

1. There is no enabling law to end political dynasties

Section 26, Article II of the Constitution says that the State “shall guarantee equal access to opportunities for public service and prohibit political dynasties as may be defined by law,” yet the country has continued to be ruled by the elite few in modern times. Why is that?

The answer lies in “as may be defined by law.” Specifically, there is no “enabling law” that will allow this specific provision to be implemented. In fact, one such anti-dynasty bill stayed stuck at the Congress’ committee level for almost three decades before it ever reached sponsorship on May 2014. Even then, it has little chance of ever getting passed in Congress since its members are made up of political dynasties.

The Supreme Court has twice upheld the view that the anti-dynasty provision of the Constitution is essentially toothless without the enabling law. Without it, political dynasties will never go away.

2. There is also no enabling law for a People’s Initiative

Two specific provisions of the Constitution (Section 2, Article XVII and Section 32, Article VI) clearly speak of the right of the people through an initiative to propose amendments to the Constitution and of Congress to provide an enabling law so that they may practice such a right.

Although an enabling law—RA 6735—does exist, the Supreme Court struck it down in 1997 for being inadequate. According to the high tribunal’s ruling, the law only pertains to people’s initiative on the making of local and national laws and not on amendments to the Constitution itself.

However, that ruling was far from unanimous. No less than former Chief Justice Artemio Panganiban and Reynato Puno dissented and said the law was sufficient for a people’s initiative. While the former ruling was not re-visited in another landmark case in 2007, both ex-chief justices expressed hope that the Supreme Court would someday review and overturn their decision.

3. Congress’ power to amend or revise the Constitution is vaguely worded

Perhaps one of the most controversial provisions one can find in the 1987 Constitution concerns the mode by which Congress can amend or revise it. While Section 1, Article XVII—which states that Congress, upon a vote of three-fourths of all its members, can propose any amendment or revision—may sound simple enough, the provision has sparked a firestorm of debates over its very vague wordings.

For one, it does not say whether Congress—composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate—should vote either jointly or separately. According to retired Chief Justice Reynato Puno, the members of the Constitutional Commission could have experienced a “senior moment” when they formulated that provision under the belief that the post-Marcos legislature would be “unicameral” (composed of only one body, as was done during the late strongman’s Batasang Pambansa) instead of “bicameral.”

Also, the provision does not specify whether both bodies should first convene as a Constituent Assembly or simply remain as is when they propose amendments or revisions. It’s no wonder that any move for Charter Change has been unsuccessful up to now.

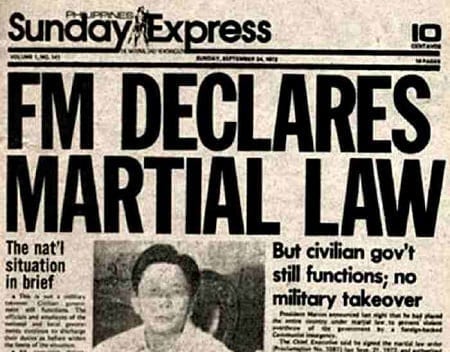

4. Repealing Martial Law is now a numbers game

It cannot be denied that the 1987 Constitution was constructed in reaction to the excesses of President Marcos’ regime. Under the new Constitution, the president’s powers to declare martial law and suspend the writ of habeas corpus have been severely clipped.

The new provisions—found in Section 18, Article VII—states that the president can impose martial law for only sixty days at the most. He then must report to the Congress within forty-eight hours after his proclamation the reason for such issuance. The House of Representatives and the Senate, voting jointly, can either revoke or extend the duration of martial law. Additionally, any citizen can question the proclamation before the Supreme Court.

Also Read: 9 Philippine Government Agencies That Need To Reform Right Now

While the safeguards look good on paper, remember that the House outnumbers the Senate by more than two hundred. In essence, the president can indefinitely extend martial law as long as he has the numbers on his side. No less than Rene Sarmiento, one of the members of the Constitutional Commission acknowledged that provisional oversight. He explained that at the time of its formulation, he and his fellow members did not see that someday the House of Representatives might be dominated by allies of the president.

5. A president can still run for “re-election.”

As we’ve said, the 1987 Constitution placed severe limits on the presidency to ensure no one ever abuses that position again. Still, there are always loopholes to find on such restrictions, as was the case when the COMELEC allowed former President Erap Estrada to run again in 2010.

Apparently, Estrada—the president from 1998 to 2001 before he resigned—convinced the election body that Section 4, Article VII prohibited only “sitting” presidents, those who finished their terms, and those who succeeded as such and served for more than four years from running again. As he did not fall under any of the categories, he was technically eligible to run again.

However, expert constitutionalist Father Joaquin Bernas said the provision explicitly prohibited any kind of president from ever seeking re-election. According to him, members of the Constitutional Commission debated whether to allow one immediate re-election, re-election as long as it wasn’t immediate or no re-election absolutely.

In the end, the “no re-election” provision was chosen, hence the constitutional wording “the President shall not be eligible for any re-election.”

6. The Commission On Human Rights is a lame duck agency

A unique feature of the 1987 Constitution, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) was created in order to investigate abuses and ensure that human rights are upheld at all times. Its various powers and functions are enumerated under Section 18, Article XIII of the Constitution.

Noticeably absent, however, is the “prosecutory” power sorely needed by it. According to a landmark Supreme Court case, the CHR can only perform the powers explicitly given to it by the Constitution. It cannot, however, perform the functions of a court or even that of a quasi-judicial body. Consequently, the restrictions have essentially made the CHR a “lame duck” agency.

Although a bill has been filed by Senator Francis Escudero to expand its powers, it will take some time before the CHR can be given its teeth.

7. The impeachment process is open to abuse

While impeachment is the penultimate way we can remove erring government officials including the president, the vice president, Supreme Court justices, the Ombudsman, and members of the Constitutional Commissions from their posts, such a process is not immune to abuse.

A landmark Supreme Court decision in 2003 which ruled that impeachment is initiated the moment the verified complaint is filed and sent to the House of Representatives’ Committee on Justice regardless of its substance and whether the Committee accepts it by majority vote had huge implications.

For one, it meant that anybody could file a poorly-written complaint just to trigger the one-year prohibition on filing another impeachment complaint against the official in question. Allegedly, former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s allies exploited this little loophole when they continuously filed weak impeachment complaints against her to pre-empt the real ones, thus ensuring she would remain in office for another year.

8. Some of the impeachable offenses are not well-defined

Section 2, Article XI of the Constitution enumerates the various offenses for which the impeachable officials can be held liable: culpable violation of the Constitution, treason, bribery, graft and corruption, other high crimes, or betrayal of public trust.

While the nature of the first four is straightforward enough, the last two (high crimes and betrayal of public trust) are not as clearly defined. What constitutes high crimes and betrayal of public trust?

For years, the Supreme Court declined to define betrayal of public trust and high crimes, labeling such as political questions that must be left for the legislature to decide. Fortunately, a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 gave us an idea of what betrayal of public trust is.

Taking a cue from the members of the Constitutional Commission, the tribunal defined the offense as acts which “may be less than criminal but must be attended by bad faith and of such gravity and seriousness as the other grounds of impeachment.” Similarly, high crimes should also be interpreted as those acts which place them in the same league as the other impeachable offenses.

9. An “impeached” official can get a pardon

Did former President Arroyo inadvertently open a new loophole when she granted her predecessor Estrada a pardon?

Section 19, Article VII states that “except in cases of impeachment, or as otherwise provided in this Constitution, the President may grant reprieves, commutations and pardons, and remit fines and forfeitures, after conviction of final judgment,” a wording that has triggered debates.

Those who supported Estrada’s pardon—including Father Bernas—said he was eligible for a pardon since his impeachment never ended in a final conviction and because what was being pardoned was his conviction for plunder before the Sandiganbayan. On the other hand, those who opposed the pardon reasoned that the “conviction by final judgment” clause excludes cases of impeachment. Whatever the case, it looks like Estrada’s pardon has set the precedent.

10. The Judiciary is not as “independent” as we think

As the third co-equal branch of government, the judiciary is tasked with the important role of settling cases and interpreting the law. As such, it is supposed to be free and independent of the whims of the executive and the legislative branch.

However, the judiciary has an apparent Achilles heel in the form of judicial appointment, a power exercised by the president. Specifically, it is the latter’s prerogative to select and reject the appointments of the judges and justices of the country.

Using such a wide-ranging power, the president can return the shortlist of nominees to the judiciary handed to him by the Judicial and Bar Council. He can order the Secretary of Justice and the congressional member of the Council to nominate his preferred candidate. As to the Supreme Court, he can appoint as Chief Justice someone who has never even served in the high tribunal.

Lastly, the president can also make his own committees to investigate the nominees and candidates before and after they have been screened by the JBC, an action which has resulted in the propagation of the padrino (patronage) system.

References

Arcangel, X. (2014). Retired SC justices say amending Constitution should be done through ‘con-ass’.GMA News Online. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/dcVheo

Bernas, J. (2007). Analysis: Only Arroyo can forfeit pardon benefits. INQUIRER.net. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/9SNyy6

Calica, A. (2007). Chiz wants to give CHR power to prosecute. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/x5unBX

Casauay, A. (2014). Anti-political dynasty bill reaches House plenary. Rappler. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/tbWcRC

Chen, A. (2014). Constitutionalism in Asia in the Early Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press.

Fonbuena, C. (2007). Newsbreak: Prosecutors to challenge Erap pardon before Supreme Court. GMA News Online. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/UkKa7c

Merueñas, M. (2014). SC junks anti-political dynasty plea anew. GMA News Online. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/4H0xou

Pedrasa, I. (2012). SC defines for the first time ‘betrayal of public trust’. ABS-CBNnews.com. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/UtVL5K

Tan, K. (2010). Comelec allows Erap to run for President in May 10 polls. GMA News Online. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/lTW8Bg

VERA Files,. (2012). Few limits to president’s power of judicial appointment. Retrieved 1 December 2014, from http://goo.gl/grBfR4

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net