How An Elephant Became Pre-War Manila’s Walking Alarm Clock

It’s one of those unbelievable tales that would have been worthy of a space in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not.

In fact, when people first heard about it, most of them were skeptical. Some even dismissed it as a hoax. For the Roces household, however, the elephant living in their garden was anything but a lie.

The patriarch, Rafael Roces, bought the young Sumatran elephant from a visiting circus sometime in 1927. While looking for a wider space for the large mammal, he decided it would be best to let the elephant be a temporary part of their family. For a while, the elephant stayed in the garden of their home located in the corner of Oroquieta and Zurbaran streets.

Also Read: Rhinoceroses, tigers, and dwarf elephants once lived in the Philippines

As told by his son Alejandro R. Roces (who would later become a National Artist for Literature), the elephant created a buzz not just in their neighborhood but in the whole of Manila. Still, others refused to believe it. They thought it was just a “goyo,” a local term which means somebody was playing a prank on them.

Soon, the elephant was christened Goyo, after the cold reception it initially received from the public.

The atmosphere changed when people started flocking to the Roces residence to view the elephant for free. Upon seeing the young pachyderm at close range, their disbelief was quickly replaced by fascination.

News about Goyo spread like wildfire. The crowd became so overwhelming that the young Alejandro and his family totally lost their privacy. The time had finally come to convince the Manila mayor to move Goyo into his permanent home–the Mehan Gardens.

The Star of Manila’s Original Zoo

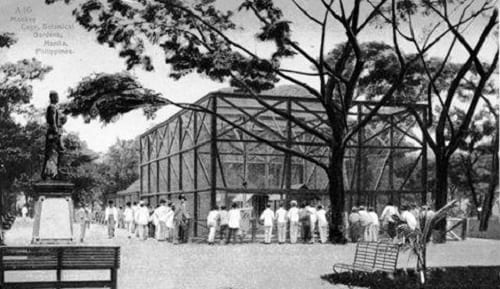

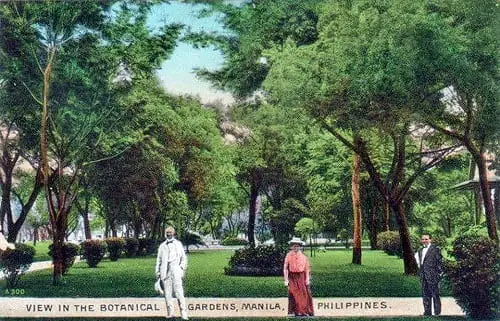

Mehan Gardens during Goyo’s time was a tourist draw. A stroll within its botanical garden could provide a brief education about the Philippines’ rich flora. The mini zoo was a relatively recent addition by the Americans, who are also credited for changing the name of the place in 1913 into Mehan Gardens after the American sanitation chief John C. Mehans.

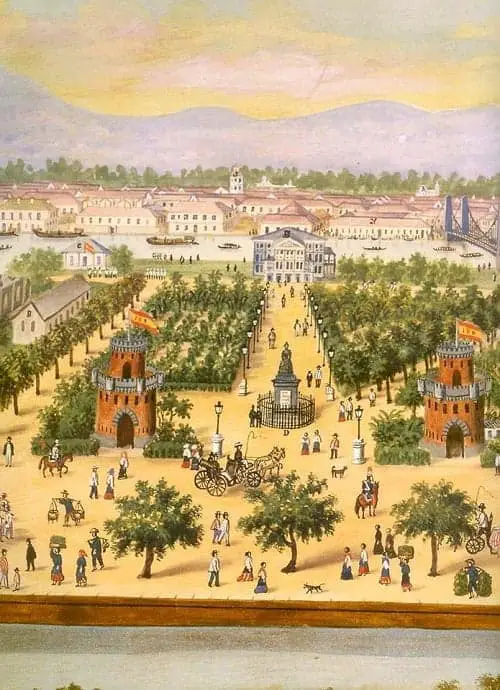

During the Spanish colonial period, the place where the garden now stands was known as Jardin Botanico. But contrary to popular belief, Mehan Gardens and the Spanish-era Jardin Botanico are not exactly the same thing.

With the help of a late 19th-century street plan of Manila, the National Historical Institute concluded that Mehan Gardens was actually just a part of the older, larger complex that was Jardin Botanico. The latter also included the present-day Liwasang Bonifacio, Manila Metropolitan Theater, and the Bonifacio artwork near the Manila City Hall.

Jardin Botanico, or the Royal Botanical Garden of Manila, was established in 1858 by a decree of the then Governor General Fernando de Norzagaray. Prior to this, the area was the site of a 16th-century Parián, the same place where the first three books in the country–including the “Doctrina Christiana en lengua Española y Tagala”–were published.

When Goyo became part of the Mehan Gardens mini zoo in the pre-war days, he officially joined a growing family of animals which included a crocodile, a bear, and a couple of monkeys led by an African chimpanzee named “Louise.”

By virtue of his size, Goyo became the zoo’s top attraction, providing larger-than-life entertainment and education to Manileños who grew up in an era of silent films.

It was also in this period when the young E. Aguilar Cruz, or “Abé” to his friends, decided to leave Escuela de Bellas Artes to become a self-made painter and writer. Originally from Pampanga, Abé efficiently adapted in his new home that by the time his sister Belen followed him in Manila in 1933, he already knew every nook and cranny of the Manila jungle.

READ: Whatever happened to Manila Zoo’s giraffes?

In a biography written by Nick Joaquin for her brother, Belen recalls the time she spent in the 1930s Manila, specifically the Mehan Gardens where she met the most famous celebrity animal at that time–Goyo:

“When we went to market in Quiapo, Abe and I walked from Calle Muralla to Plaza Lawton, passing the Metropolitan Theater on our way to the Colgante Bridge, across which was the Quiapo market. Sometimes Abe took me to the Mehan Gardens behind the Met, to look at the wild elephants in the zoo where the main attraction was Goyo, the kind old elephant. Abe was my tourist guide then; he’d take me to the top of the walls, where there were cozy parks from which you could see the Luneta and the Legislative Building and the Escolta skyline.”

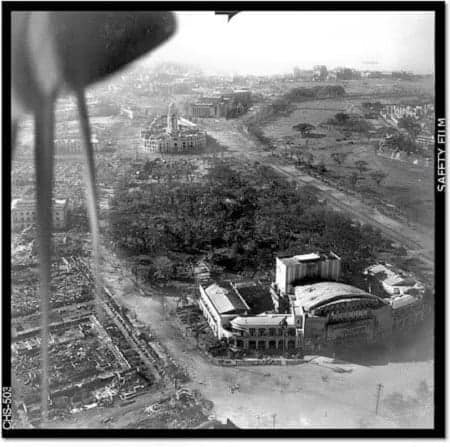

The Met, short for Manila Metropolitan Theater, was built in front of the Mehan Gardens a few years after Goyo‘s arrival. Until it was destroyed by heavy bombings during WWII, this Art Deco style theater served as pre-war Manila’s premier cultural center. A street called Calle R. Basa separates the theater from the Mehan Gardens behind it.

Also Read: 20 Beautiful Old Manila Buildings That No Longer Exist

In the 1930s when the zoo and Goyo were still existing, Calle R. Basa was Manila’s main flower market–a reputation now owned by Dangwa in the Sampaloc area. The street is a fitting tribute to Filipino illustrator Regino Garcia y Basa, who drew the plants featured in the landmark 19th-century botanical book Floro de Filipinas by Fr. Manuel Blanco.

Also Read: 17 Most Unusual Street Names in Manila (And Their Origins)

More Than Just an Elephant

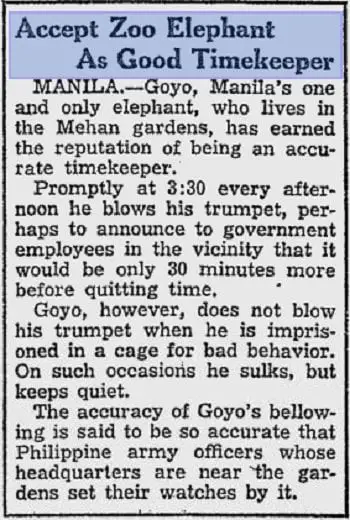

Goyo‘s fame reached its peak when American newspapers featured his story in 1939. The said article, published in dailies like Reading Eagle and Mt. Adams Sun, focused primarily on Goyo’s “hidden talent”–i.e., his habit of blowing his trumpet at exactly the same time every day.

Every afternoon, at 3:30 PM, Goyo would always make a sound which, as time went by, became a signal for employees nearby that there were only 30 minutes left before the working day is over.

It was said that Goyo became a very reliable “timekeeper,” so much so that Philippine army officers whose headquarters were near the Mehan Gardens set their watches based on the time of his bellow.

But just like present-day Manila Zoo’s Mali, who has spent her entire lonely life inside a small concrete pen, Goyo also failed to experience the life he deserved. By 1938, the iron cage that welcomed him when he first entered the zoo was becoming too small for the jumbo-sized Goyo.

Also Read: 11 Things You Never Knew About General Gregorio “Goyo” Del Pilar

In fact, a writer for The American Chamber of Commerce Journal observed that the poor animal’s back was probably 4 or 5 inches away from his prison’s iron roofing.

The suffering of Goyo and the rest of Mehan Gardens’ zoo animals culminated in the early days of Japanese Occupation. Without anyone to attend to their needs, the poor creatures suffered neglect and starvation.

In 1941, Goyo and the rest of the zoo animals who once sacrificed their freedom to entertain and educate many Filipinos died of malnutrition.

The zoo of Mehan Gardens is long gone, but the memories of Goyo still remains. May this story constantly remind us that animals like Goyo also deserve a place in our history, if that will be the only way to save others like him who have been languishing in solitary confinement–all for the sake of ‘educating’ the masses.

References

Harper, B. (2001). Mehan Garden. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/ESYt4C

Ira, L. (1977). Streets of Manila (pp. 167-168). Quezon City, Philippines: GCF Books.

Joaquin, N. (2006). Abe: A Frank Sketch of E. Aguilar Cruz (pp. 15-19). Angeles City, Philippines: The Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies, Holy Angel University.

Just Little Things. (1938). The American Chamber Of Commerce Journal, 18(11).

Mt. Adams Sun,. (1939). Accept Zoo Elephant As Good Timekeeper. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/diJSJm

Ocampo, A. (2001). Mehan Gardens controversy. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/d5JbYm

Roces, A. (2000). Looking for Liling: A Family History of World War II Martyr Rafael R. Roces, Jr (p. 120). Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Roces, A. (2004). It’s Environment Month. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 18 June 2016, from http://goo.gl/nYV6zA

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net