8 Extremely Interesting Lesser-Known Battles in Philippine History

Throughout its history, countless battles have been fought on Philippine soil yet we probably know only a few of them. A shame actually, since many of them are actually interesting and educational from a historical point of view

While it’s good we know about the more-famous battles, it’s better we also learn about the lesser-known but just as remarkable conflicts that once took place in the Philippines.

Also Read: 8 Epic Battles in History Where Filipinos Kicked Ass

1. Cagayan Battles (1582).

Japanese samurai versus European soldiers? It may sound a little hard to believe, but such a cultural faceoff really happened when the Spanish encountered a pirate settlement near the river of Cagayan in Luzon.

Led by their chief Tay Fusa, the pirates—composed of Chinese mercenaries, Japanese “ronin” (masterless samurai) and other lawless elements—subjugated and oppressed the people of Cagayan, compelling the Spanish to send a relief force of forty men led by Capt. Juan Pable de Carrion onboard six ships.

Set against this small expedition was an enemy force composed of approximately 600 men and more than a dozen ships. In the ensuing battles (which included beach warfare and actual boarding of ships) the Spanish utilized their superior weaponry and military tactics to inflict hundreds of casualties on the pirates with only a few deaths on their side. In the end, Tay Fusa and his men were forced to abandon their settlement.

2. Tamblot Uprising (1621 – 1622).

If you’ve ever heard of the biblical story about Elijah challenging the priests of Baal to see whose god could rain fire from the heavens, then this uprising also had a similar showdown albeit with reversed results.

Tamblot, a babaylan from Bohol, was said to have started the revolt after he challenged the Spanish priest to see whose god could help them produce rice and wine from a bamboo stalk. While Tamblot won the challenge, the Spanish attributed his victory either to demonic forces or plain trickery. Nevertheless, Tamblot convinced 2,000 Boholanos to abandon the Spanish and instead join his cause.

Also Read: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

Due to the uprising, the Spanish had to call for reinforcements from Cebu to defeat the rebels. As for Tamblot’s fate, he was either killed in one of the battles or was assassinated by some Spanish friars who managed to infiltrate his camp.

3. Bancao Revolt (1621 – 1622).

Concurrent with the uprising by Tamblot in Bohol was the Bancao Revolt which happened in Leyte and was led by the aging Datu Bancao of Limasawa.

As a young man, he had been one of those who initially befriended Spanish conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi and converted to Catholicism. However, during his dotage, he went back to his old religion and teamed up with the local babaylan Pagali to build a temple dedicated to a diwata.

Also Read: 6 Badass Filipina Warriors You Never Heard Of

Bancao and Pagali also attracted lots of followers by saying they could turn the Spanish into stones or clay by simply uttering the word “bato” or hurling earth at them respectively. Unfortunately for the followers, their incantations proved useless to the might of superior Western technology as the Spanish suppressed their movement soon enough and burned their temple.

Afterward, the Spanish beheaded Bancao’s corpse and placed his head on a stake as a warning to the rest of the people.

4. Tapar Uprising (1663).

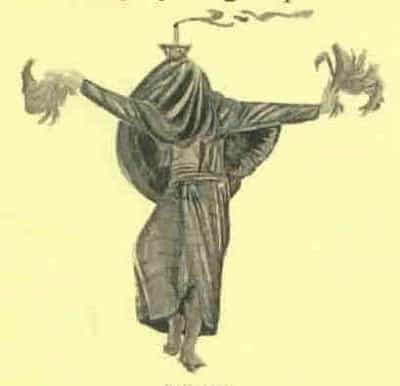

This revolt, which happened in the town of Oton, Panay, was named after its chief instigator, a babaylan named Tapar.

Renouncing his conversion to the Catholic faith, Tapar founded a religion which mixed Christianity and paganism. As its head priest, Tapar dressed in women’s clothes, claimed he could talk to a demon, and formulated native versions of the Spanish clergy, the Holy Trinity, and even the Virgin Mary.

When the local Spanish priest tried to intervene, Tapar had him killed. As revenge, Spanish forces hunted down Tapar and his followers and killed them. To dissuade further revolts, they fastened Tapar and his followers’ corpses to bamboo poles and fed them to the crocodiles in full view of the inhabitants. Not only that, they also impaled the movement’s Virgin Mary and fed her to the crocs as well.

Recommended Article: 6 Reasons Why Ramon Magsaysay Was The Best President Ever

5. Chinese Massacres (1603, 1639, 1663).

It sure was tough to be Chinese living in the Spanish-controlled Philippines, considering they had to endure discrimination, violence, and whole-scale massacres.

Thanks to the failed attempt by the Chinese pirate Limahong to annex the country in 574, anti-Chinese sentiment generally ran high among the Filipinos and the Spanish. Distrust was a two-way street, however, as most of the Chinese also viewed the other side with suspicion. It didn’t help that some of them actually plotted to revolt against Spain.

In this atmosphere of paranoia, several bloody revolts broke out in the 16th century and 17th century. Among the most notable include the Sangley (the archaic term for Chinese) Rebellion of 1603 in which a combined Spanish-Filipino-Japanese force massacred 23,000 Chinese after it was feared the arrival of three high-ranking mainland Chinese officers was a pretext for an invasion.

Recommended Article: A Brief History Of Filipinos’ Obsession With White Skin

Another, the 1639 Rebellion, involved an uprising by Chinese workers in Laguna which later ended with the deaths of an estimated 20,000 Chinese. The third major rebellion happened in 1662 when the powerful Chinese pirate Koxinga demanded the annexation of the Philippines but abruptly died afterward. His death, however, sparked another battle between the Spanish and the Chinese which ultimately resulted in the latter suffering 22,000 deaths.

Unfortunately, no amount of bloodshed could induce the two sides to seek a lasting peace, as there would be more uprisings and rebellions as Spanish rule dragged on.

6. Sultan Shaif ud-Din versus Sultan Kutai (1701).

While single combat to the death between two monarchs might seem like something out of a Hollywood movie, an event like this really took place in 1701 between two Muslim sultans due to a simple misunderstanding.

Wanting to pay a courtesy call to Kutai who was Sultan of Maguindanao and the successor of Kudarat, Sulu Sultan Shaif ud-Din sailed forth from Jolo to Maguindanao with a huge fleet of native sailboats. However, Kutai wrongly assumed the vast armada to be an invasion force and denied it permission to sail upriver.

Trivia: The first Muslim to be a senator hailed from Jolo. Find out who

Insulted by the gesture, ud-Din challenged Kutai to single combat in front of their men. After both killed each other during the duel, their men also fought a bloody battle which was won in the end by ud-Din’s forces.

7. Agrarian Revolts (1745 – 1746).

Set in the areas of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Rizal, and Bulacan, the roots of the Agrarian Revolts stemmed from the usurpation of lands by several religious orders, leaving the inhabitants poor and desolate.

While Spanish forces eventually quelled the uprisings, Pedro Calderon, an investigator for the Royal Audiencia, found that the religious orders—with the collaboration of a corrupt surveyor named Juan Monroy—usurped the lands rightfully belonging to the natives and ordered the lands to be returned to their rightful owners.

Recommended Article: 7 Myths About Spanish Colonial Period Filipinos Should All Stop Believing

The case eventually reached the court of Spanish King Ferdinand VI who admonished the friars and commanded them to return the ill-gotten lands back to the inhabitants. Not only that, but he also instructed the religious orders to treat the Filipinos well.

Unfortunately, the king’s decrees fell on deaf ears as the friars managed to keep their vast haciendas and estates until the Revolution broke out.

8. Revolt in Defence of the 1812 Constitution (1815).

One of the least-known revolts in the country happened after the rescission of the 1812 Cadiz Constitution. As can be recalled, that particular constitution—promulgated during a time when Spain was embroiled in a bloody guerrilla war known as the Peninsular War with the French—granted a wide range of rights which was afforded to the different Spanish colonies including the Philippines.

Among such rights included representation in the Spanish assembly and Spanish citizenship to the natives. Unfortunately, with the withdrawal of the French and the reinstatement of the Spanish King Ferdinand VII, the constitution was later abolished in 1814. Naturally, this resulted in widespread unrest in the Philippines.

Also Read: 12 Random Facts About Manila That Will Blow Your Mind

Many of the lower classes blamed the upper-class “principales” for the loss of their newly-minted freedoms and suspected them of conspiring with the Spanish to maintain the latter’s hegemony. Ilocandia became the hotbed of the insurgency, with local leader Simon Tomas leading his townmates to ransack and pillage the homes and churches of the Spanish and pro-Spanish Filipinos.

However, their revolt was short-lived as the Spanish quickly suppressed Tomas and his followers.

References

Ang, J. Historical Timeline of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu Including Related Events of Neighboring Peoples. SEAsite Project. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/LlHJxQ

Borao, J. (1998). The massacre of 1603: Chinese perception of the Spaniards in the Philippines.Itinerario, 23(1), 22-39.

Dayon Cortesanon,. (2010). How Tamblot could have tricked the friar. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/2Hxl7U

Funtecha, H. (2007). The Tapar uprising in Oton, Iloilo. The News Today. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/oO0ByL

Official Website of the Province of Laguna,. Remembering the Chinese Massacres in Laguna (1603 and 1639). Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/iwqSSj

Official Website of the Provincial Government of Cagayan,. History of Cagayan. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/IhYAEm

The Kahimyang Project,. (2012). The Bancao rebellion of 1622 in Carigara, Leyte. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://goo.gl/3v5OsJ

Philippine History Module-based Learning I’ 2002 Edition by Rebecca Ramilo Ongsotto, Reena R. Ongsotto

The Spanish Experience in Taiwan 1626-1642: The Baroque Ending of a Renaissance Endeavor by Jose Eugenio Borao

Philippine History by Maria Christine N. Halili

The Inhabitants of the Philippines by Frederic H. Sawyer

The Philippines: A Global Studies Handbook by Damon L. Woods

Struggle for Freedom: A Textbook on Philippine History 2008 Edition by Attyu. Cecilio D. Duka

Historical Dictionary of the Philippines by Artemio R. Guillermo

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net