Whatever Happened To Manila’s Merlion?

Products need branding so consumers can easily remember them.

The same goes for countries who want to give their tourism industry a boost. After all, a postcard-worthy landmark is what defines a must-visit city: Paris has Eiffel Tower, New York City has the Statue of Liberty, and Kuala Lumpur has the Petronas Twin Towers.

Singapore is another fine example. Although it is and always has been the “Lion City,” Singapore’s official mascot, the Merlion, didn’t exist until 1964 when the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (now the Singapore Tourism Board) adopted the half-fish, half-lion as its emblem.

Also Read: Whatever Happened To Manila’s Statue of Liberty?

For the record, Singapore’s Merlion was not an imitation. When the symbol was first conceived, its creators had in their mind the story that supposedly gave Singapore its present name. Legend has it that in the 11th century, a prince named Nila Utama (also known as Prince Nilatanam) reached an island of what was then known as Tumasek which means “sea” in Javanese.

According to Malay Annals, Nila Utama saw a strange animal as soon as he landed on the island. He was told that it was a lion, hence he changed the island’s name into “Singapura” (from the word singa which is the Sanskrit for lion).

Take note that it wasn’t clear whether the animal was indeed a lion or a tiger, which is indigenous to the island. What is known though is that early Indian settlers of Singapore worshiped the goddess Mariamman who has a lion as her sacred beast.

Now let’s go back to the Merlion. Its lion head obviously represents this ancient island of “Singapura” and the mysterious animal it was named after. Singapore first used the lion as its official symbol in the 1950s through its State Crest, also known as the National Coat of Arms. The merlion’s lower half, on the other hand, symbolizes Singapore’s rich history and current prosperity as a port city.

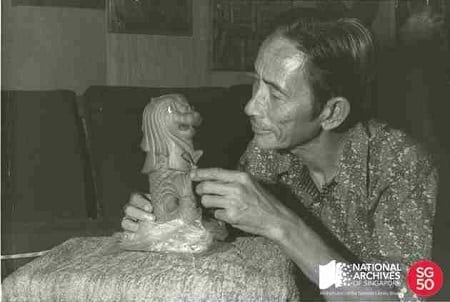

Mr. Lim Nang Seng sculpting a miniature Merlion Statue, 1972. Photo Credit: National Archives of Singapore

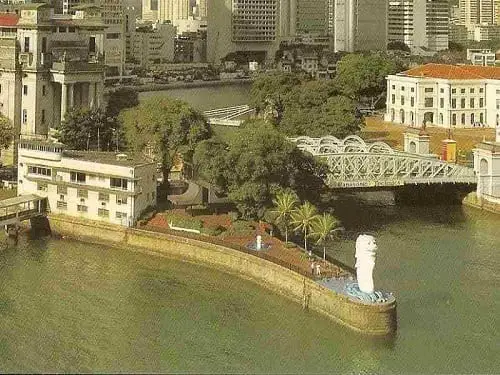

Several years later, in 1972, the 8.6 meters high merlion statue–made by a local sculptor named Lim Nang Seng–was officially installed at the mouth of Singapore River. Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew hoped that the Merlion (which cost $165,000 to complete) would be associated with Singapore.

And he was right: since its unveiling, the statue has become the icon of the now-progressive city-state.

Such has been the success of Singapore’s branding that most Filipinos often overlook the similar creature in Manila’s official seal. Seemingly obscured by the emblem’s overall lackluster design is the half lion, half fish symbolizing the “authority of the City Government – protective and defensive of Manila’s people & territory.”

But unlike Singapore’s merlion, Manila’s sea-lion traces its roots to an earlier period.

The legendary creature, also known as “morse,” had long been an element of Western heraldry.

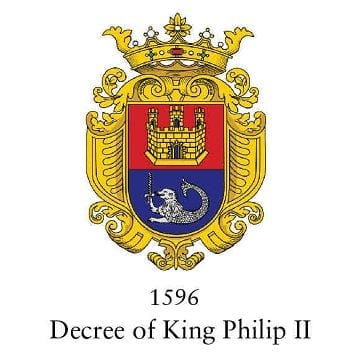

On March 20, 1596, the Distinguished and Ever Loyal City of Manila was granted its first coat of arms by King Philip II of Spain. One of its symbols was a sea-lion which he described as:

“…..a half lion and half dolphin of silver, armed and langued gules—that is to say, with red nails and tongue. The said lion shall hold in his paw a sword with guard and hilt.”

The coat of arms was first adopted on May 30, 1596, and had since been used in the city’s flags, pendants, and shields. The sea-lion was alternatively called Ultramar, from the Latin words ultra which means “from beyond” and mar which means “sea.”

This makes sense because in classical heraldry, the lion “represented the lands of the Kingdom of Spain, whose might extended across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in a vast Spanish Empire.”

Related Article: The Real-Life Fairy Tale That Changed Philippine History Forever

The same Spanish City Seal with the legendary half-lion, half-dolphin can still be found in every bottle of the century-old San Miguel Beer. A winged sea-lion with a crown and a sword also made its way to the Legazpi and Urdaneta Monument in Rizal Park.

As fate would have it, Manila’s first city seal underwent a series of changes that saw its tower of Castile being replaced by a pearl in a shell, reinforcing the city’s reputation as the Pearl of the Orient. The sea-lion, although evolved, still remains as the symbol of Manila. It has also been adopted by the Philippine Presidency, where it “connotes strength and determination,” as well as different government agencies.

Its counterpart in Singapore, meanwhile, is no longer the emblem of the Singapore Tourism Board (STB). However, the half-fish, half lion that has long been associated with their country continues to be protected under Section 24 of the Singapore Tourism Board Act (Chapter 305B). This speaks volumes about how Singaporeans respect and value their national symbol.

Now, if the sea-lion had been used as a symbol in the Philippines long before Singapore introduced the merlion to establish their identity, why then that the latter outdid the former?

Perhaps it all boils down to effective branding. Or maybe it mirrors our blatant disregard of our history and national heritage (looking at you, Torre de Manila!). Either way, the Merlion has a lot of lessons to teach.

References

Manila.gov.ph,. The City’s Official Seal. Retrieved 12 August 2015, from http://goo.gl/eko3vq

National Archives of Singapore,. (2015). Mr. Lim Nang Seng Sculpting A Miniature Merlion Statue, 1972. Retrieved 12 August 2015, from http://goo.gl/lBB7uK

Ocampo, A. (2012). Looking Back 6: Prehistoric Philippines (p. 21). Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Presidential Museum and Library,. (2015). The Ancient Archipelagic Ultramar: Symbol of Manila, The Presidency, And The Philippines. Retrieved 12 August 2015, from http://goo.gl/3ahTXd

Singapore Tourism Board,. STB-owned Assets – Merlion Symbol. Retrieved 12 August 2015, from https://goo.gl/HT57Tc

Singapore.sg,. National Coat of Arms. Retrieved 12 August 2015, from http://goo.gl/SdWVNH

Su San, L. (1972). S’pore symbol: 26ft-high Merlion. The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/NnPl4r

The Straits Times,. (1964). Lion with fish tail is Tourist Board’s new emblem, p. 6. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/jv7zz1

The Straits Times,. (1964). The story behind the ‘Merlion’ emblem, p. 13. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/1B98ev

The Straits Times,. (1967). Use of Merlion emblem: Warning by the Tourist Board, p. 4. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/vEqOm4

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net