12 Astonishing Lesser-Known Attractions at the National Museum

For some of the younger Filipinos, the idea of spending time at the National Museum of the Philippines is so 10 years ago–something you only do because it’s part of a mandatory field trip.

Also Read: 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History

However, there’s more to our national museum than Juan Luna’s famous Spoliarium and The Parisian Life. Here are just some of the most fascinating yet often overlooked treasures from our country’s flagship museum:

1. Masuso pots.

The masuso pots (or breast pots) are ceramic objects the origin and cultural significance of which are still unknown. The complete lack of data was the result of looting and destruction of archaeological sites.

Two variations of the masuso pot can be viewed at the National Museum: one with four breasts and another one with breasts facing seven directions.

READ: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

Interestingly, historical evidence suggests that these breast-shaped artifacts from the Philippines are somehow related to the breast pots unearthed in Peru and in the Lausitz region of Germany.

Other variations of the ancient vessel were also discovered in Romania, Ukraine, and Nigeria—all of which show evidence that the pots were most likely used as sacred water vessels or ritual pots, with the breast symbolizing the life-giving power of water.

2. Ammonite.

Discovered in the Mansalay town in Southern Mindoro, this fossil shell of an ammonite dates back to 160-175 million years ago or during the age of the dinosaurs.

An ammonite is an extinct group of mollusks related to octopus, squid, and nautilus. Hence, the existence of their fossils suggests that the Philippines was partly submerged in the ocean at the time of its formation.

Recommended Article: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

In 1940, ammonites were discovered south of Mansalay Bay near Colasi Pt. by Hollister of the National Development Company Petroleum Survey.

The formation, aptly designated as the Mansalay Formation, was the first evidence of Mesozoic Era in the country. Eight years later, several fossil shells of ammonites were once again discovered by the National Museum staff at Tignoan Creek, Mansalay.

The rich collection of old fossil shells recovered from the Mansalay town led to the latter being dubbed as the “Jurassic Park of the Philippines” by the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB).

3. Giant Spider Crab.

Known as the largest species of crab, the giant spider crab (Paromola macrocheira) is truly a sight to behold. Thankfully, the National Museum now offers people an opportunity to see one up close. The specimen, a preserved animal, was caught in Mindanao using tangle nets at a depth of 800 meters.

Also Read: Top 10 Weirdest Philippine Animals

This rare creature–which may live up to 100 years–uses both camouflage and its tough exoskeleton to protect itself from bigger marine predators.

4. “Venus” by Guillermo Tolentino.

This stunning sculpture in Plaster of Paris was made by no less than National Artist for Sculpture Guillermo Tolentino in 1951. Entitled “Venus,” this work of art was inspired by The Birth of Venus by Italian painter, Sandro Botticelli, who made it in 1486 for the Medici Court.

Unlike Botticelli’s version which shows the goddess Venus emerging from the sea and covering her private parts with her hands, Guillermo’s sculpture is much more daring–it portrays Venus with her hands in her hair as if flaunting her nude body.

To complete the sculpture, Tolentino had to work with a live model dressed in a bathing suit.

Also Read: 10 Vintage Photos of Filipinos Being Awesome

One of the new acquisitions of the National Fine Arts Museum, Tolentino’s “Venus” is currently on loan from the Ernesto and Araceli Salas Collection.

5. “Ina ng Lahi” (Mother of Filipinos) by Jose P. Alcantara.

Located at Gallery XIV on the South Wing of the National Fine Arts Museum (formerly National Art Gallery), this carved wood is one of Jose P. Alcantara’s prize-winning artworks.

Entitled “Ina ng Lahi” (Mother of Filipinos), this sculpture made from Narra wood received a special prize from the Art Association of the Philippines in 1951.

READ: Who was the first Filipina sculptor in history?

A self-taught sculptor, painter, and muralist, Alcantara’s highest recognition was when he bagged the first-place win in the first Southeast Asian Art Conference and Competition for his entry of “Behold The Man.”

Also included in his list of accolades was his victory in 1953 when the Art Association of the Philippines awarded him the first prize for the entry “Mother and Child.”

6. The Palette of Masters.

Don’t dare overlook this seemingly ordinary piece of wood: dubbed as the “Palette of Masters,” this relic has a very interesting provenance.

First owned by Carlos “Botong” V. Francisco, it was handed down to another National Artist, the legendary Fernando C. Amorsolo. Later, its ownership was transferred to other prominent artists such as Sofronio Ylanan Mendoza (SYM) and Emilio Aguilar Cruz.

Cebuano-born painter Romulo Galicano served as its final owner, and to celebrate the fascinating history of the palette, he embellished it with an untitled painting in 1997. He also did it as a gift to his wife Christy.

Also Read: Amorsolo and the Marca Demonio

A native of Carcar town in Cebu province, Galicano learned how to paint from Martino Abellana (known as the “Amorsolo of Cebu”) and was heavily influenced by the works of Fabian de la Rosa, Juan Luna, and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo.

He was associated with the Dimasalang Group which was composed of Sofronio Ylanan Mendoza, E. Aguilar Cruz, among others. Galicano and the rest of the group were known for creating landscape paintings that were reminiscent of Amorsolo’s works.

7. “El Ermitaño” by Jose Rizal.

Sculpted by Jose Rizal during his exile in Dapitan, El Ermitaño is an 1893 terra cotta figurine given as a gift to Fr. Pablo Pastells. It shows Rizal’s own interpretation of St. Paul the Hermit or Paul of Thebes, known in Catholic history as the first Christian hermit.

El Ermitaño contains inscriptions in reference to the long and controversial correspondence between Rizal and his Jesuit mentor, Fr. Pastells. The exchange of letters, which took place between September 1892 and June 1893, reveals the Jesuit priest’s attempt to win Rizal back to the Catholic church.

Also Read: 25 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

Rizal, having been excommunicated by the Spanish friars for the alleged social unrest sparked by his two novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, refused to reconcile to the Catholic church despite Pastells’ sensible use of theology.

The epistolary exchanges between Rizal and Fr. Pastells were published by Retana and Teodoro M. Kalaw in the 1900s and the 1930s, respectively. The most comprehensive work, however, was by Raul J. Bonoan S.J. in “The Rizal-Pastells Correspondence” (1994), based on the complete texts found in the Arxiu Historic S.I. de Catalunya, the Jesuit archives in Sant Cugat del Valles, Barcelona.

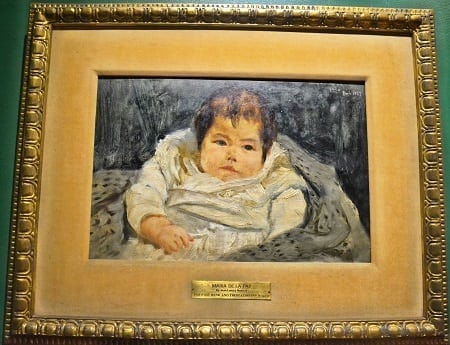

8. “Maria de la Paz” by Juan Luna.

Born on June 24, 1889, Maria de la Paz (nicknamed “Bibi”) was the second child of the Filipino painter Juan Luna and his wife, Paz Pardo de Tavera. Their firstborn was Andres Luna de San Pedro, also known as Luling and who would later make a name for himself as one of pre-war Manila’s prominent architects.

Unlike Luling, the younger Bibi was not as lucky. In March 1892, Maria de la Paz died at the age of 3. As it turned out, Bibi‘s death was only one of a series of sorrowful events that disturbed the serenity in Juan Luna’s residence.

Related Article: The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in Philippine History

Several weeks later, Luna received tragic news from the Philippines that his father had died. In September of the same year, everything culminated in one tragic incident: Luna’s murder of his wife and his mother-in-law.

9. Intramuros Pot Shard.

The Intramuros Pot Shard was only one of the 500 artifacts discovered by the National Museum team at the San Ignacio Church Ruins in Intramuros, Manila. However, this archaeological piece was the most significant for one reason: It was the only artifact with ancient inscription recovered systematically.

Found 140 centimeters below the brick floor of the San Ignacio Church in 2008, the Intramuros Pot Shard shows the native Filipinos’ earliest form of writing.

Its discovery was an important milestone in Philippine archaeology as there were only a few artifacts with ancient inscription recovered in the past: the Laguna copper plate (900 AD), Butuan ivory seal (9th to 12th centuries), Butuan silver strip (14th to 15th centuries) and the Calatagan pot (15th century).

The Intramuros Pot Shard was found associated with Ming Dynasty ceramics dating back to 15th – 16th centuries A.D. The excavation was a joint project by the Intramuros Administration and the Cultural Properties and Archaeology Divisions of the National Museum.

As for the inscription, it was later deciphered by Mrs. Esperanza B. Gatbonton, a Cultural Heritage Advocate. By comparing the scripts with tagalog and kapampangan, she came up with a tentative translation: “pa-la-ki” which can be interpreted as “a-la-ke” or “alay kay.”

10. Butuan Ivory Seal.

Another archaeological piece with the ancient inscription, the Butuan Ivory Seal was recovered in the 1970s by pot hunters in a prehistoric shell midden site in Ambangan, Libertad, Butuan City in Agusan del Norte.

Made of rhinoceros ivory tusk, the object must have been used to stamp documents or goods during trading.

Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma first saw the ivory seal in 1990 at a conference in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The ancient script was written in Javanese or stylized Kavi, said to be related to the Tagalog script. Postma deciphered the seal and read the script as “But-ban.” Other experts theorize that the script could also stand for “But-wan” since the letters “b” and “w” were commonly interchanged.

Butuan was the center of trade and commerce in the country as early as the 10th century.

11. Spot-billed Pelican.

The Spot-billed Pelican (Pelecanus philippensis) is the only species of pelican ever recorded in the Philippines.

These birds once thrived in Laguna de Bay, Candaba swamp, and in the coastal areas of Bulacan and some areas in Mindanao (Gulf of Davao, Lake Buluan, and Liguasan marsh). Hunting, growth of invasive plants, agricultural development, and a host of other threats led to its ultimate extinction in the Philippines in the 1940s.

Also Read: Top 10 Endangered Birds in the Philippines

Characterized by their white feathers, dark feet, and spotted bill and pouch, these pelicans have limited population today in India, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia while no occurrence or sighting has been reported in Myanmar, China, and the Philippines.

Although there was a recent sighting reported in Leyte by a team from Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), it is believed that the said bird could be a Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus).

12. Sword artifacts of Japanese mercenaries on San Diego.

San Diego was a Spanish battleship that clashed with a Dutch ship Mauritius on December 14, 1600, just off Manila Bay.

At the helm of San Diego was Antonio de Morga, the lieutenant governor of the Philippines who took the leadership of the vessel with hopes of gaining recognition from King Philip II of Spain.

However, De Morga was not the best man for the job, and the citizens from Manila knew it from the start. Hence, to avoid sailing with De Morga, these Spaniards allegedly recruited Japanese mercenaries to supplement the fighting contingent on board San Diego.

The Japanese samurai (or bushi) were actually Japanese Christians who fled to Manila in search of sanctuary. These brave soldiers who were recruited to join San Diego brought with them a dagger or tanto as well as two types of swords: the longer katana and the shorter wakizashi.

Also Read: San Diego’s Astrolabe

Prior to the battle, San Diego was seriously overloaded. In addition to the hundreds of passengers, there were also “14 cannons, 127 barrels of gunpowder, thousands of cannonballs and musket balls, hundreds of jars for provisions” on board.

This only attested Captain Juan de Alcega’s (Vice-Admiral of the fleet) claim that “(on board) there were too many people, too many weapons, and too much ammunition…”

In the end, San Diego was no match to the more powerful Dutch ship. It sank with hundreds of its passengers and countless potteries, pieces of jewelry, ceramics, and weapons.

In 1992, an expedition led by Frack Goddio recovered the remains of San Diego.

Although most of the swords have vanished, some of those that survived severe corrosion–including the tsubas or samurai sword guards (see photo above)–prove once and for all that Japanese mercenaries were among the passengers of the doomed ship.

References

Bacobo, D. (2001). Epistles at dawn, Rizal duels Pastells. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/kohJqA

Bird Life International,. Spot-billed Pelican (Pelecanus philippensis). Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/H606aY

Fish, S. (2011). The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific : with an Annotated List of the Transpacific Galleons, 1565-1815 (p. 243). AuthorHouse.

Goddio, F. Ancient Trade Routes – San Diego. FrankGoddio.org. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/QCbqxt

JoseRizal.ph,. Sculptures Made by Rizal. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/SxcK7X

Labro, V. (2009). ‘Extinct’ pelican rediscovered in Leyte. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/uMHV5q

McCoy, A. (2009). An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines (pp. 374-375). Univ of Wisconsin Press.

Museums of the Philippines – An Online Guide,. Butuan Ivory Seal. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from https://goo.gl/KNiiku

National Museum Collections,. (2014). Ammonites. Retrieved 23 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/nyRMMv

National Museum Collections,. Butuan Ivory Seal. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/6iM9XK

Ocampo, A. (2000). Guillermo Tolentino, national artist for sculpture. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. 9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/2uNi6M

Ocampo, A. (2008). Recommendations for a rainy day. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 25 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/QgiDKC

Pamaran, M. (2015). Mindoro students ‘discover’ Jurassic town. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 23 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/XlkjSF

Richer de Forges, B., & Ng, P. (2007). New records and new species of Homolidae de Haan, 1839, from the Philippines and French Polynesia. The Raffles Bulletin Of Zoology, 16, 36.

Suppressed History Archives,. Breastpots. Retrieved 23 May 2015, from http://goo.gl/E3Sbct

Thaindian News,. (2008). Shard find in Philippines shows an ancient form of writing. Retrieved 5 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/54cjWr

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net