“Flag Of Our Mothers”: Little-Known Facts About The Trio Who Made The Philippine Flag

Editor’s note: This work was republished with permission by the Manila Bulletin. This is the original article.

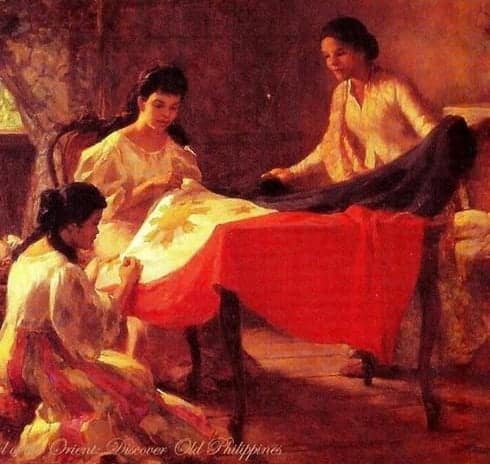

Fernando Amorsolo’s “The Making of the Philippine Flag” and Napoleon Abueva’s sculpture with the same subjects have something in common.

Both works of art, although revered for their outstanding craftsmanship, have perpetuated the misleading idea that our first flag was made by three grown-up women.

It doesn’t help that our history books are rife with information that put more emphasis on the flag itself than on the three women who turned Aguinaldo’s sketch into a tangible reality.

No mention of their struggles to polish the flag’s minute details, nor of the fact that one of them was a child who could have spent her time playing patintero, and that their roles as flagmakers were more important than we give them credit for.

History In a Thimble

Sitting inside a glass case somewhere at Malacañang Museum is an antique thimble supposedly used by Marcela Agoncillo to sew the original Philippine flag. It is said that it only took her five days with the help of her daughter and a family friend to complete the flag.

But the story of how she became the principal seamstress of our first flag started all the way back in her childhood.

Born in the embroidery capital of Taal, Batangas, Doña Marcela learned the basics of needlework from the Beaterio de Santa Catalina, a convent school for girls in Intramuros. She married another Batangueño, Felipe Agoncillo, who would later become the first Filipino diplomat.

The Agoncillos was an illustrious but patriotic family. They involved themselves in several causes concerning their countrymen. Don Felipe even once put a sign on his door that says “To the poor: Open at all hours, free services.”

Soon, the Spanish colonial officials accused him of being a filibustero or enemy of the State and Church, prompting him to escape to Yokohama via a Japanese vessel, later transferring to Hong Kong, then a British colony.

Doña Marcela, along with their three daughters, followed Don Felipe after 22 months. To support her family, she had to sell the jewelry that was once part of their family heirlooms. She also sewed and sold children’s pinafores in Hong Kong to bolster her income.

Their residence at 535 Morrison Hill Road in Wan Chai eventually welcomed other Filipino revolutionary exiles like General Antonio Luna who, as Doña Marcela recalled, was fond of cooking European dishes.

Another notable figure who took refuge in the Agoncillo residence was Emilio Aguinaldo, who was exiled to Hong Kong following the signing of Pact of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.

While in the British colony, the general founded the Hong Kong Junta with Felipe Agoncillo. The movement served as their eyes and ears that followed the political developments in their home country.

Having been told of Doña Marcela’s knack for embroidery, Aguinaldo asked the Agoncillo matriarch to do a pivotal project—the making of the first Philippine flag.

Flag of Our Mothers

During the Philippine Revolution, what was once considered a useless art spawned creations that boosted the morale of men in the battlefields. The fine skill of embroidery was used by women to create revolutionary flags and banners, which in turn inspired the men, so much so that they became a source of protection or anting-anting.

Women took pride in lending their skills for the Revolution, so did Doña Marcela when she accepted the responsibility given by Aguinaldo. With the help of her seven-year-old daughter Lorenza Agoncillo and Rizal’s niece, Josefina (or Delfina in other sources) Herbosa Natividad, Doña Marcela meticulously cut, sewed and embroidered the silk cloth she bought from a nearby store.

The painstaking process took a little bit of trial and error. Doña Marcela recounted that she and Natividad “unstitched what was already sewn simply because a ray was crooked, or because the stars were not… equidistant.” After five laborious days, the flag was finally complete.

The 1898 flag is slightly different from the Philippine flag we know today. It features an anthropomorphic sun as well as open and closed laurel wreaths surrounding an inscription in the center.

The text in the obverse reads Fuerzas Expeditionarias del Norte de Luzon (Expeditionary Forces of Northern Luzon) while the reverse shows the words Libertad Justicia e Ygualdad (Liberty, Justice, and Equality).

Doña Marcela personally delivered the flag to Aguinaldo on May 17, 1898 shortly before he set sail for Manila on board the ship McCulloch. Several days later, the same flag was unfurled from the window of Aguinaldo’s house in Kawit, Cavite, during which Philippine independence as we know it today was officially proclaimed.

Three Women, One Flag

Although most of us are familiar with what became of the first Philippine flag, the same cannot be said for the trio who breathed life into Aguinaldo’s design.

Doña Marcela, or Lola Celay as she was fondly called later in life, gave birth to two more daughters. They all grew up to become accomplished women in the society, with Gregoria (or Goring) becoming the first Filipina to graduate from the prestigious Oxford University.

Lola Celay continued to support her husband Felipe when he became the country’s first diplomat who fought hard to make other countries recognize our independence. After returning to the Philippines, Don Felipe became engaged in public service while Doña Marcela spent most of her time in charitable activities.

Lorenza or Enchang, the child who assisted her mother in sewing the Filipino flag, dedicated her life to teaching. She taught at the Malate Catholic School for 50 years, a feat duly recognized by the institution through a plaque of merit. Lorenza died at the ripe old age of 81 in 1972.

Delfina Herbosa-Natividad’s life, although short, was equally meaningful. Before she cemented her place in Philippine history as a flagmaker, she was a Katipunera. She joined the revolutionary group at the tender age of 13, fueled by the injustices of the Spaniards against her uncle, the martyr Jose Rizal, and her own father who was denied of a Christian burial simply because he had not gone to confession.

As a young Katipunera, she fought several battles along with her husband Jose Salvador Natividad, one of the revolutionary leaders at Biak-na-Bato who were exiled in Hong Kong. Little is known about her final years but the tragic death of her daughter reportedly sent her into a downward spiral leading to her untimely death in 1900 at the age of 21.

A housewife, a seven-year-old child, and a young Katipunera. One fateful day in 1898, these three women had their paths converge in Hong Kong to create a flag that symbolized the rebirth of a nation.

A flag that brings with it stories of patriotism, heartbreaks, and struggles of the trio who represented all the unsung heroines of the Revolution, young and old. Stories that will continue to inspire the heroes in us—if only we open our ears.

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net