11 Things From Philippine History Everyone Pictures Incorrectly

The passage of time, wrong information, and inaccurate portrayals have left us picturing famous events just a way bit off-tangent.

For the benefit of enlightenment then, let us look at some of the famous events from Philippine history we’ve been picturing incorrectly and see them for what they really are—warts and all.

Also Read: 5 Historic Lies You Were Taught In School

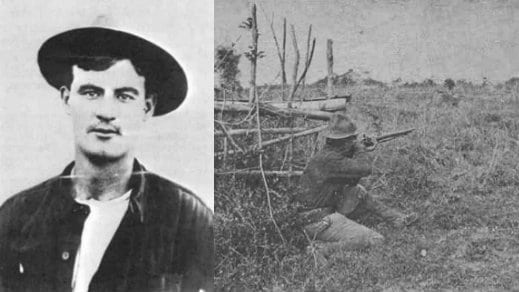

1. The first shot of the Philippine-American War didn’t happen on a bridge

What you’re picturing: The first shot of the Philippine-American War was fired on the San Juan Bridge.

The reality: As taught to us so many times during our history class, the first shot which started the Philippine-American War was supposed to have taken place on San Juan Bridge. However, it actually happened on Sociego Street in Sta. Mesa. In fact, the marker has since been moved by the National Historical Institute to a corner of Sociego and Silencio streets.

Related Article: 8 Dark Chapters of Filipino-American History We Rarely Talk About

Also, it is interesting to note that the entire war was started by an Englishman. Yes, Private William Grayson—the man who fired the first shot—was a full-blooded Anglo who later immigrated to Nebraska with his parents when he was still a child.

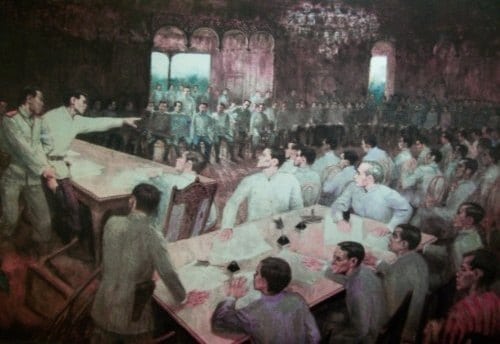

2. Those who attended the Tejeros Convention were Magdiwang, not Magdalo

What you’re picturing: The Tejeros Convention of 1897 was dominated by members of the Magdalo faction led by Emilio Aguinaldo, leading to the latter being elected as the President.

Also Read: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonifacio

The reality: While it was true that Andres Bonifacio had the odds stacked against him at the Tejeros Convention, we’d just like to point out that majority of those present belonged to the Magdiwang faction of which Bonifacio himself was associated with.

In fact, other than Aguinaldo, the rest who won positions in the new government (Mariano Trias, Artemio Ricarte, Emiliano Riege de Dios) were all Magdiwang. Also of note was that Magdiwang controlled a more powerful army and larger territory than Magdalo.

So, what gives? Why was Bonifacio still defeated? Did both factions band together for the common good, or did they fall prey to regionalism? Can we trust the accounts of those who attended the said convention?

Inevitably, the infamous Tejeros Convention will have to remain as one of the raging controversies of Philippine history.

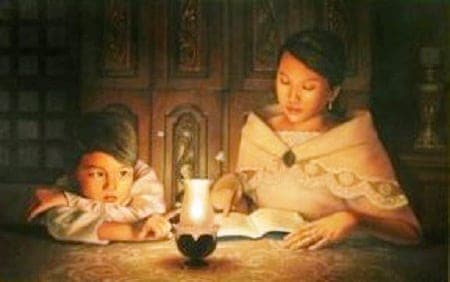

3. Jose Rizal was a naughty boy in the famous “Moth and Lamp” story

What you’re picturing: Little Jose Rizal was an obedient child who listened attentively as her mother told him the “moth and lamp” story.

The reality: Perhaps no other story sums up Rizal’s childhood so succinctly as his famous story about the lamp and the moth. And despite what you may think, little Rizal was actually being naughty.

Instead of reading a Spanish children’s book diligently given to him by his mother Teodora, he was instead doodling caricatures on its pages. Even after being scolded, he did not pay much attention to the book, instead focusing his gaze on some moths that were flying around a coconut oil lamp.

READ: 25 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

To get his attention, Lolay (Rizal’s mom’s nickname) decided to finally tell a story about moths in Tagalog. Sure enough, little Jose attentively listened but never loosened his gaze on the flying moths. And contrary to popular belief, one of the moths met its doom by falling and drowning into the coconut oil after its wings got burned, but not by the fire itself.

Still, Rizal would never forget the moths, which he in his grown-up years described as “no longer insignificant to him” after that fateful episode.

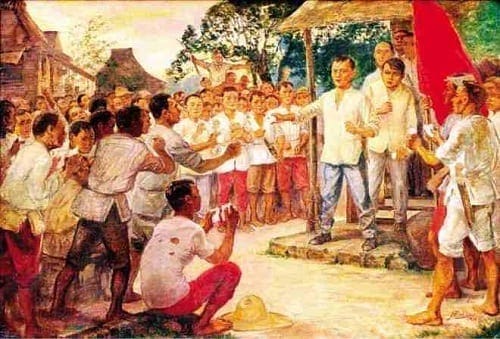

4. The Cry of Balintawak (or Cry of Pugadlawin, etc.) was a series of meetings

What you’re picturing: The Cry of Balintawak (or whatever other historians call it) is synonymous to the tearing of cedulas (community tax certificates) by members of the Katipunan led by Andres Bonifacio.

The reality: To simplify this monumental event as one where Bonifacio and his followers cried for a revolution outside someone’s yard and tore apart their cedulas would do it an injustice.

Also Read: The Myth of Bonifacio’s “SOKA” (State of the Katipunan Address)

In fact, Bonifacio and other top-ranking members of the Katipunan would repeatedly meet and discuss behind closed doors during those fateful days when the Spanish authorities discovered their existence.

Also, not all leaders of the Katipunan were in favor of the uprising (three of them being Teodoro Plata, Briccio Pantas and Pio Valenzuela). It was only after Bonifacio managed to implead the majority that the revolution finally got underway; the tearing of the cedulas was a mere afterthought (which could be the reason why there are so many differing accounts of the “Cry”).

Also Read: 10 Little-Known Facts About The Katipunan

Again, to sum it up, there was a series of hotly-debated meetings, a plea for patriotism, and finally an overwhelming decision to finally rise up against the Spanish. Real history is sometimes much more badass than the legend itself.

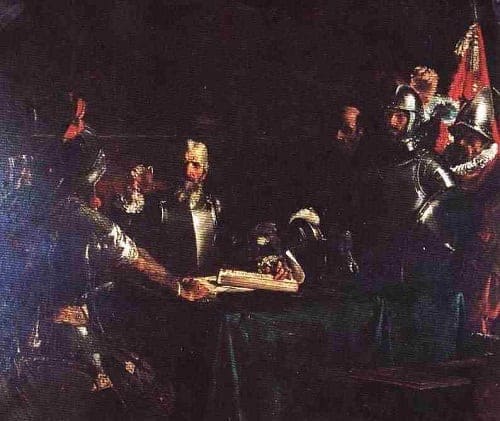

5. Blood compacts were made by drawing blood on the chest, not arms

What you’re picturing: In 1565, Spanish explorer Miguel Lopez de Legazpi entered into a blood compact (sandugo) with Bohol’s Datu Sikatuna. The ritual was done by drawing blood from their arms, mixing it with wine, and drinking the said mixture from a cup.

The reality: Contrary to popular belief, those famous blood compacts which signified a peace treaty between the Spaniards and the natives were not done by drawing blood on the arms, but on the chest.

The incision was usually made below the breast which was to signify how far the participants would be willing to defend each other’s lives. It also manifested the great trust both parties placed on each other (imagine having a blade so near the heart).

Did you know? The blood compact between Miguel López de Legazpi and Rajah Sikatuna was not the first in the country.

As for the misconception that drawing blood was done on the arms, the mix-up could be attributed to the Katipunan members’ practice of drawing blood on the arms and using it to sign their oath of membership. In time, the blood compacts also came to be wrongly associated with the Katipunan method.

6. Gregorio del Pilar died early due to his own carelessness

What you’re picturing: Gregorio del Pilar was the last man to die at the Battle of Tirad Pass, desperately charging into battle with his white horse whilst clutching a saber before falling to the superior firearms of the Americans.

READ: 11 Things You Never Knew About Gregorio Del Pilar

The reality: As fate would have it, del Pilar actually died early in the battle—and it was due to his own carelessness.

According to his lieutenant Telesforo Carrasco, del Pilar himself decided to participate in combat after finding out the Americans were being pushed back early on. A few minutes into the battle, he raised his head because of the tall cogon grass and ordered his men to stop firing because he wanted to see the American position.

Carrasco warned the boy general that he should crouch down because he was being targeted. Unfortunately, no sooner than he said that, an American bullet found its mark and shot through del Pilar’s neck, killing him instantly.

READ: 10 Most Infamous Traitors in Philippine History

Ironically, American general Henry Ware Lawton also met his end earlier in the same way—shot in the chest after standing carelessly exposed in a heated battle.

7. Ferdinand Marcos wasn’t the first to proclaim the Martial Law

What you’re picturing: President Ferdinand Marcos was the first and only person who proclaimed martial law in 1972.

Also Read: Martial Law was communism’s biggest recruiter

The reality: We may have the image of a strong-faced Marcos pointedly telling us why he declared martial law on television. However, credit for the first declaration belongs to his Minister of Public Information Francisco “Kit” Tatad who delivered the proclamation on air at 3 PM of September 23, 1972.

Marcos himself would go on air much later, at 7:15 PM of the same evening.

8. Jose Rizal was finished off with a bullet to the head

What you’re picturing: Jose Rizal’s ultimate sacrifice ended with the exclamation point of him turning his back and facing the sun in one last act of defiance against Spanish tyranny.

READ: 9 Reasons Why Rizal Was Just As Human As The Rest Of Us

The reality: While we won’t debate whether his “twist” was deliberate or accidental, we’d point out Rizal’s execution was completed with the “tiro de gracia” or the mercy blow to really make sure he was dead.

After Rizal fell, a medical officer went up to his body to feel his pulse (he didn’t declare whether he was still alive or not), and beckoned for a soldier to shoot Rizal in the head.

The soldier who gave the final blow was, in fact, the Spanish commander of the firing squad who, after doing the deed, took out Rizal’s bloodied handkerchief and covered his face with it.

Also of note was the surreal atmosphere surrounding the execution. While a somber mood dominated the Filipino crowd, the Spanish present (including the friars) treated the whole event as a virtual fiesta, with makeshift viewing stages set up around the execution grounds.

9. Andres Bonifacio fought with a revolver, not a bolo

What you’re picturing: Andres Bonifacio is usually portrayed in movies and statues as a rugged camisa de chino-wearing man wielding a revolver and bolo.

The reality: While undoubtedly badass, Bonifacio in his lifetime preferred to fight with a revolver and was not known to use a bolo at all.

It showed in many instances, such as during the Battle of San Juan, or during the time when he tried to kill Daniel Tirona at the Tejeros Convention. In fact, Bonifacio—in his correspondence with other high-ranking Katipunan members—repeatedly mentioned and emphasized the use of firearms.

Also Read: 7 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Andres Bonifacio

The perennial image of a bolo-wielding Bonifacio can be attributed to Isabelo de los Reyes, the founder of the Aglipayan Church and whose accounts characterized the revolution as a plebeian struggle.

His writings inspired sculptor Ramon Martinez to immortalize Bonifacio in his 1911 Balintawak monument as the bolo-wielding and flag-holding barefooted peasant who fought for the masses.

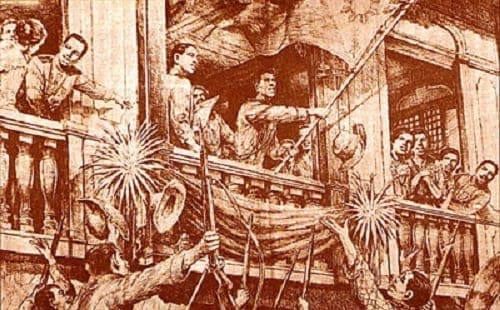

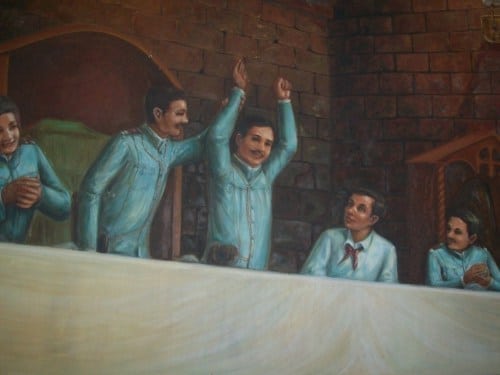

10. Emilio Aguinaldo never waved the Philippine flag, nor was it done on a balcony

What you’re picturing: Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed independence on a balcony of his mansion while waving the Philippine flag in the early morning of June 12, 1898.

The reality: Actually, it was Jose Rizal’s distant relative, a lawyer named Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, who read the Act of the Declaration of Independence in the late afternoon in front of an open window. In fact, Aguinaldo added the balcony only sometime in 1919 to 1921.

READ: 7 Curious Facts About Emilio Aguinaldo

Also, while it was Aguinaldo who unfurled the flag, it was Bautista who ended up waving it in front of a jubilant crowd.

Lastly, contrary to popular belief, the flag had already flown twice before its official unfurling—at Cavite Nuevo’s Teatro Caviteño after the Filipino victory at the Battle of Alapan, and again at the Spanish barracks after another Filipino win in Binakayan.

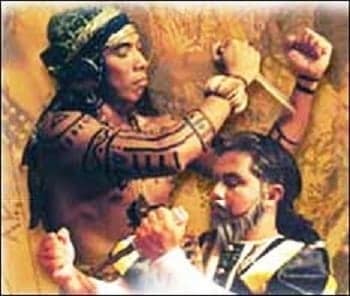

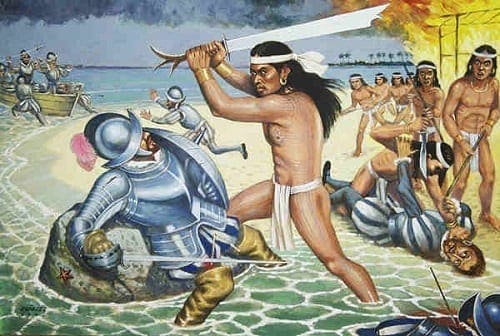

11. Lapu-Lapu and Magellan never actually dueled

What you’re picturing: Lapu-Lapu killed Ferdinand Magellan in an epic one-on-one fight.

Also Read: Meet Bambalito, The First Warrior-Hero Who Died Fighting For Our Freedom

The reality: While there was much glory to be had for Lapu-Lapu and his men for fending off the invaders from Spain, (begrudging) respect should also be given to Magellan for going down as a true warrior should.

While things initially went well for the Spaniards (yes, they were winning the battle early on with their armor and guns), Magellan and his few dozen men eventually buckled under the endless assault of more than a thousand natives they were fighting in the densely-forested islands of Mactan.

It didn’t help that the Mactanis started targeting their legs and arms after noticing they were left un-armored. In the end, it was the heavily injured Magellan (he took a poisoned arrow to the leg, in addition to several slashes and stab wounds in his extremities and face) who alone faced off against the natives after he stayed behind to let his men get away, managing to injure and kill a few of them until he was finally overwhelmed and killed on the beach.

Also Read: 0 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Cebu

So, for all the bravery Lapu-Lapu displayed in defying the Spanish, we also have to give credit to Magellan for making a last stand worthy of a Hollywood movie.

References

Diario de Filipinas,. (2011). Exclusive Interview – An Eyewitness Account of Rizal’s Execution. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/EHJDKQ

Dumindin, A. (2006). First Shot of the War, Feb. 4, 1899. Philippine-American War, 1899-1902. Retrieved 23 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/0ZfYsV

History House,. Magellan’s Demise. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/j6DBQd

Nery, J. (2012). Who put the bolo in Bonifacio’s hand?. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/fiOgm5

Ocampo, A. (2002). The moth and the lamp. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. 7. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/ru775c

Ocampo, A. (2009). Legaspi’s wish list. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/oiMIeP

Ocampo, A. (2012). Was Bonifacio ambidextrous?. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/bgKNZR

Ocampo, A. (2013). Bohol and the blood compact. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/QG0i10

Ocampo, A. (2013). The three ‘balimbing’. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 23 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/sUsKmU

The Kahimyang Project,. (2011). Today in Philippine History, December 2, 1899, the Battle of Tirad Pass took place. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/kqI8Fy

The Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines,. Declaration of Martial Law. Retrieved 24 March 2015, from http://goo.gl/XLB7i7

Additional References:

Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration by Fergus Fleming

The Borough of Licab by George F. Esguerra

Waiting for General MacArthur by Virgilio I. Gonzales

Basques in the Philippines by Marciano R. De Borja

The I Stories: The Events in the Philippine Revolution and the Filipino-American War as Told by its Eyewitnesses and Participants by Augusto De Viana

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net