7 Fascinating Ways Filipinos Amused Themselves Before Television

Unless you’re one of the elite, living in the Philippines before the 20th century was not exactly a bed of roses.

The indio constantly dealt with hunger and discrimination. The wealthy class, on the other hand, enjoyed all the luxuries within their reach.

Speaking of luxury, their idea of ‘entertainment’ is very different from ours. So, if you can’t survive a week without Netflix binge-watching or Facebook stalking, this era would have definitely bored you to tears.

Let’s look back at some of the fascinating ways our forefathers entertained themselves long before TV and the Internet shortened our attention span.

1. Watching Animal Gladiators Destroy Each Other

In contrast to the more “cultured” elite who patronized the theater and opera house, leisure for the regular Filipinos usually revolved around cockfighting or the less popular bullfighting.

It’s hard to deny the impact that cockfighting has had on the Filipino society. The popularity of the game peaked during the Spanish colonial period, so much so that it became a regular source of income for the government.

Bullfights, meanwhile, had fewer fan base. Most considered it as a knockoff of its Spanish counterpart. Not surprisingly, both the animals and the bullfighters often gave subpar performances.

As noted by Margherita Arlina Hamm, author of “Manila and the Philippines” (1898), “[i]n place of the fierce Andalusian [sic] bulls which are bred for ring purposes, they have low spirited and decrepit animals of the Philippines.”

Short-lived as it was, bullfights, especially those held in the suburb of Ermita, attracted many curious eyes and greedy betters. One memorable fight–if you can even call it as such–happened one afternoon sometime in the 1890s.

Also Read: 29 Things You’ll Never See in Manila Again

By that time, the popularity of the gory game was already waning in the Philippines. In his 1899 book “Yesterdays in the Philippines,” Joseph Earle Stevens recounted how the organizers desperately tried to pit a Spanish bull and a Bengal tiger against each other.

The scene would have driven any animal rights advocate mad. Fortunately, even with the help of firecrackers and a heated pitchfork, the two animals refused to fatally attack each other.

As observed by Stevens, “there seemed to be no hard feeling at all between the two beasts, and the tiger only wanted to get at the gentleman outside of the cage, not at the bull.”

After a few mild attacks, the animals just couldn’t be bothered anymore, leaving the almost three thousand audiences that day quite disappointed. After the trainer called it a day, the animals were shipped to another country. And that’s how one of the last few performances at the Plaza de Toros de Manila concluded.

Despite making a brief comeback in the 1950s, bullfighting never returned nor cemented its place in the Filipino culture.

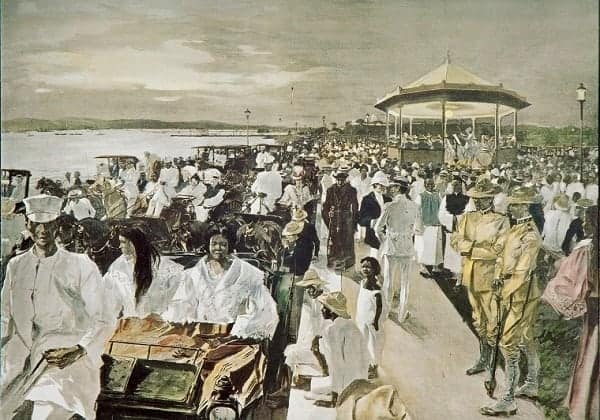

2. Listening to Luneta’s World-Class Band Concerts

The Spanish-era Luneta was not only known as a place of execution. It was (and still is) a leisure ground where people from all walks of life could unwind and witness the sunset after a hard day’s work.

What makes the 19th-century Luneta different from the Luneta of today is the presence of a bandstand. World-class musicians, such as the legendary Philippine Constabulary Band, once performed in this area to serenade the people strolling at the park.

Listening to relaxing band concerts was one of the reasons why people frequented this place. Luneta gave them an incredible opportunity to hear soothing music, long before portable music players were even considered possible.

American entrepreneur Joseph Earle Stevens, who stayed in the Philippines from 1894 to 1896, has perhaps the most vivid and nostalgic description of Luneta in its heyday:

“the far-famed seaside promenade called the Luneta, where society takes its airing after the heat of the day is over. Imagine an elliptical plaza, about a thousand feet long, situated just above the low beach which borders the bay. . . . In the centre of the raised ellipse is the band-stand, and on every afternoon, from six to eight, all Manila come here to feel the breeze, hear the music, and see their neighbors.“

Such was the impact of Luneta and its enchanting music on a foreign personality that a famous park in the U.S. took inspiration from it.

Also Read: The Controversial “Luneta Tower” That Was Never Built

First Lady Helen Herron Taft stayed in the Philippines in the early 1900s, back when her husband was still serving as civil governor. In her memoirs entitled Recollections of Full Years, she recounted how Luneta inspired her to make a similar park in Washington called the Potomac. She envisioned the latter as:

“a glorified Luneta where all Washington could meet, either on foot or in vehicles, at five o’clock on certain evenings, listen to band concerts and enjoy such recreation as no other spot in Washington could afford.”

3. Attending Home Parties

Entertainment for the Manila’s elite was ‘social entertainment.’ This could mean attending family reunions during which each of them showcased refined tastes and skills in music, poetry, dance, and virtual arts.

Or, they could be invited by someone to attend events where they could hobnob with other members of the social circles. These included the tertulia, which is a simple get-together with a touch of poetry and music; bailes, or dances for formal balls; and bodas, a wedding celebration with artistic/literary overtones.

Also Read: 1 Old Colorized Photos Reveal The Fascinating Filipino Life Between 1900 – 1960

Events like these were usually held on the second floor of the host’s European-inspired house. These were also an opportune time for different families to prove they had a sense of urbanindad, defined as “a delicacy in taste, graceful and studied gestures, extreme politeness, a desire for knowledge, artistic accomplishment, stylish attire, knowledge of world history and geography, and a fancy home.”

4. Playing panguingue

Apart from cockfighting, Filipinos in the 19th century who had nothing productive to do often engaged themselves in “panguingue.” This is a card game similar to rummy, usually played with eight or ten decks.

Such was its popularity during the Spanish colonial period that it was regularly depicted in various illustrations and artworks from that era. One of them was drawn by Charles Wirgman, a British artist who visited Asia in the 1850s as a special correspondent for the Illustrated London News (ILN).

Wirgman gave the following description for the illustration displayed above:

“I send you a sketch of a card-party–or, as card-playing is here called, Panguingui; the parties being given in little bamboo huts, furnished with a table and benches. The apartment is dimly lighted by a cocoa-nut oil lamp suspended from the ceiling, which illuminates the faces of the picturesque gamblers, and gives a theatrical effect to the scene. The striped shirts, old straw hats, and handkerchiefs bound round their heads, are more picturesque than would be a better-regulated costume. The women are also players.“

What probably started as an innocuous activity gradually became a full-blown vice. In fact, one newspaper editorial perfectly demonstrated how gambling had corrupted the Filipina through a drawing that shows her head stuck in a trash bin labeled “panguingue” with all the evils leaking from it, namely: estafa (fraud), robo (thievery) and adulterio (adultery).

The dangers of panguingue also didn’t escape the consciousness of leading 19th-century Filipino intellectuals. Jose Rizal, in his 1889 letter addressed to the twenty young women of Malolos, underscored some of the bad qualities he despised in a woman:

“…..a woman whose kindness of character is expressed by mumbled prayers; who knows nothing by heart but awits, novenas, and the alleged miracles; whose amusement consists in playing panguingue or in the frequent confession of the same sins?”

Also Read: 36 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

Rizal’s fellow propagandist, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, likewise put panguingue in a very bad light in his letter to his niece dated March 13, 1889:

“Cherish knowledge not only for yourself but that posterity may have received it from you and bless you for this legacy. Surely, for this you may well sacrifice a few hours a day, the few hours you waste so carelessly in “panguingue” and idle gossip.”

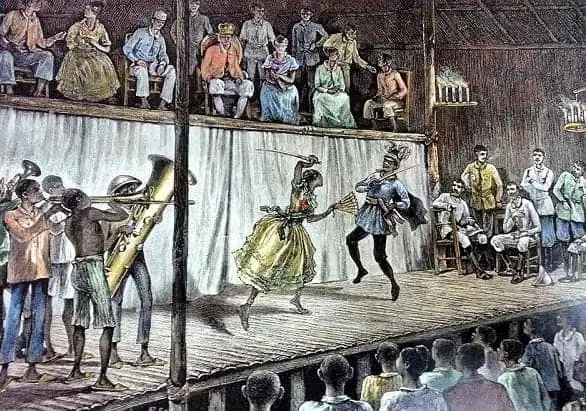

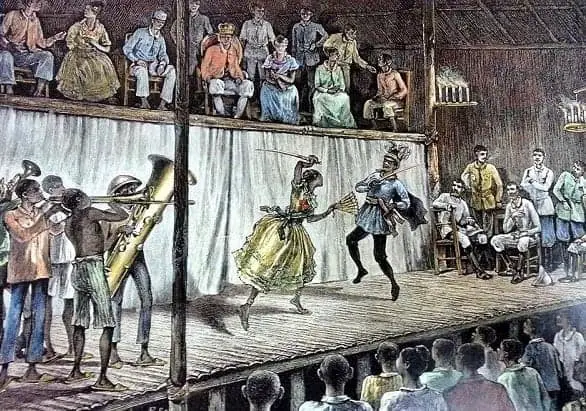

5. Watching Anti-Muslim comedy a.k.a “moro-moro.”

The Spaniards hated the Moros (a term referring to the Philippine Muslims) so much that they wrote and popularized a play just to demonize them.

Known as the “moro-moro” (or linambay in Cebu), this 19th-century comedy was usually performed during a week-long celebration leading up to the town fiesta. It reached the height of popularity before it was replaced by bodabil, cines and zarzuela.

Also Read: 9 Pinoy Historical “Bad Guys” Who Weren’t As Bad As You Think

Its origin remains debatable. Some sources agree that it took inspiration from the 17th-century victory of Governor-General Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera over the Maguindanao warriors led by Sultan Kudarat. Others believe it took shape from the reenactment done by the people in Manila shortly after they learned of the Moros’ defeat in the said battle.

“Moro-moro” performances were among the most anticipated events in the Spanish colonial Philippines–and everyone involved took it seriously. In fact, each town assigned a Comite de Festejos to collect the funds needed to build the stage where the comedy would be performed.

Some of the wealthier members of the townsfolk sponsored the costumes and jewelries while others gladly volunteered to supply the band music to accompany the marches and battles in the play.

Laced with anti-Muslim propaganda, “moro-moro” often has a Christian prince who is “handsome, manly and corteous” as a protagonist. The Moros, meanwhile, are depicted as the “bad guys” who abducted the princesses, attacked Christian kingdoms and killed innocent people they met along the way. The latter usually wore elaborate, shiny costumes and a headdress called purong.

READ: Meet the Terrifying Moro Warriors and Heroes of WWII

The play, usually held for three to nine days and attended by Filipinos from different social classes, was not just a simple theatrical performance. It became a tool for the Spaniards to reinforce the superiority of Roman Catholicism over Islam, and the idea that the only way to salvation is through conversion to the colonizers’ religion.

When the Spanish colonial rule was over, the popularity of “moro-moro” declined, too. Although the tradition continues to this day in some parts of the country, this comedy is now generally perceived as a dying art, a memento from an era that once created division between Filipino Christians and Muslims.

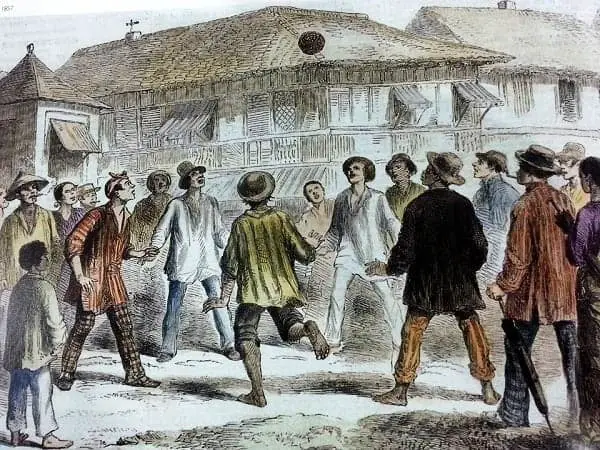

6. Playing “football” in The Streets

Long before we started our love affair with basketball, Filipinos were actually football aficionados. In fact, football was our primary sport during the Spanish colonial period, and one of the greatest football players in history–none other than Paulino Alcantara–was born in Iloilo City.

Charles Wirgman, a British artist who once visited Manila in the 1850s, was amazed by how Filipinos played the sport in the Manila streets. Even though football is one of England’s oldest games, Wirgman noted that he had “never seen it played with such dexterity as in Manila.”

Along with the illustration above, Wirgman also left behind an eyewitness account of how 19th-century Filipinos played the game using a ball “made of wickerwork” (think sepak takraw ball):

“They stand in a circle, and with their feet keep up the ball for any length of time……the game is never to let it touch the ground after it is once up, and always to manage to strike it with the feet. Some players are very expert at the “back-footed” trick; with the sole of their foot they will send the ball right over their heads to the players in front of them, who, in turn, send it back again. The game is a most extraordinary sight and the players are wonderfully clever at it.”

The popularity of football started to decline as soon as the Americans took over the Philippines. Even the establishment of the Philippine Football Federation in 1907 and our victory in the Far Eastern Games didn’t deter it from fading into obscurity.

Eventually, football was replaced by basketball, and Filipinos have never looked back since.

Also Read: Meet The Legendary Filipino Basketball Team Who Defeated China in Asian Olympics

7. Watching Public Executions

For the ordinary Filipinos of the yesteryear, there was no event quite as intriguing as a public execution.

It all started during the Spanish colonial period when various forms of capital punishment were introduced to the country. It ranged from burning and garrote to hanging and decapitation.

When the Spanish Codigo Penal was enacted in 1848, it became clearer that the colonizers were serious in intimidating those who were trying to challenge their authority.

It was revised during the American Occupation, with death penalty also imposed on those who committed murder, kidnapping, homicide, robbery, rape and treason, just to name a few. Some of those who violated the Sedition Law (1901); Flag Law (1907); and Brigandage Act (1902) also received capital punishment.

Also Read: 10 Surprising Facts About Death Penalty In The Philippines

Death penalty during these two era was administered both to punish the Filipino insurgents and warn the public about the consequences of breaking the rules. And what better way to achieve the latter than making execution a public spectacle?

Joseph Earle Stevens was in Manila in 1895 when the execution by garrote of two Filipinos, both in their early twenties, drew an overwhelming number of curious onlookers. In his book, “Yesterdays in the Philippines,” he recalled how the execution of the two convicts attracted the attention of people from all walks of life, driven by either morbid or scientific curiosity:

“On the fatal day, my colleague and I drove to the scene shortly after sunrise, and crowds of people had already begun to come together from the adjoining districts. Carriages of all classes rolled in from all directions. Chinamen with cues, natives with their wives, women with their infants, young girls and children, old men and maidens, were all dressed in their best clothes.“

Also Read: Interesting Jobs From Old Philippines That No Longer Exist

Some of the famous personalities who met their ends through execution were the GOMBURZA (garrote), propagandist and novelist Jose Rizal (firing squad) and revolutionary leader Macario Sakay.

References

A timeline of death penalty in the Philippines. (2006). The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) Blog. Retrieved 9 January 2017, from https://goo.gl/IHtU8K

Arroyo, N. (2017). First Lady Helen Taft’s Luneta: Remembered in Washington’s Potomac Park. The White House Historical Association. Retrieved 4 January 2017, from https://goo.gl/0N2l6p

de las Alas, J. (2011). Medieval Manila: Life at the Dawn of the 20th Century. Perspectives In The Arts And Humanities Asia, 1(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.13185/g65

Lietz, R. (1998). The Philippines in the 19th Century: A Collection of Prints (1st ed.). Makati City: RLI Gallery Systems.

Pacana, N. (2007). The Moro in “Moro Moro”: Hegemonic Representation in the Linambay Plays in Cebu. Philippine Quarterly Of Culture And Society, 35(1), 87-99. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/JNsrHH

Rizal, J. (1889). Ang Liham ni Dr. Jose Rizal sa mga Kadalagahan sa Malolos, Bulakan (1st ed.).

Siasat, J. (2014). Remembering the Philippines as a football nation. Rappler. Retrieved 9 January 2017, from https://goo.gl/opNXLg

Southeast Asian Arts: The Philippines. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 January 2017, from https://goo.gl/uXkwmq

Stevens, J. (1899). Yesterdays in the Philippines (1st ed., pp. 38-42). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net