How a Filipino Band Made History at a US President’s Inauguration

In mid-1904, the Philippine Constabulary Band arrived in St. Louis, Missouri to perform in the World’s Fair. It was their first performance in foreign soil–and in America no less.

But in an era when most Westerners perceive Filipinos as savages who couldn’t even play the flute, the pressure was on this band to impress everyone.

And so during one of their evening concerts at the fair, the band anxiously stepped into the stage to give the performance of a lifetime. Walter H. Loving, the handsome African-American who founded the band years earlier, served as their conductor. As they began playing one of the more famous symphonic pieces–Giachino Rossini’s “William Tell Overture”–the audience was immediately captivated.

Also Read: 0 Amazing Pinoy LGBTs Who Broke Barriers And Made History

Note after note, the Filipino band delighted its listeners with an unforgettable music. Soothing melody filled the concert hall, leaving the audience pleasantly surprised that the dog-eating, head-hunting Filipinos actually had the potential to become world-class musicians.

Then, the unexpected happened. In what others suspected as an act of sabotage, the power went out in the middle of the performance. The audience was on the edge of their seats. The band, meanwhile, continued playing their instruments, barely seeing the white handkerchief that Loving tied to his baton in a desperate attempt to save the performance.

What others thought would lead to their defeat propelled them instead towards victory. The band never missed a beat despite the darkness. Their persistence not only earned them two awards during the fair (second prize for the band and a bronze medal for Pedro Navarro, the piccolo player) but also put the legendary band in the annals of music history.

READ: The Mother Who Inspired “Sa Ugoy Ng Duyan”

A ‘Loving’ Touch

As Philippine insurrection reared its ugly head in the early days of Fil-Am War, the need for more US soldiers became inevitable. But the anti-imperialists wouldn’t back down; they did everything they could to prevent the continuous outflow of Americans to the bloodbath happening in the Philippines.

The U.S. Army came up with a better, more feasible idea. They started recruiting Filipinos who were willing to fight against their fellow Filipinos, whom American authorities branded as “bandits” or “insurgents.” Soon, the Philippine Scouts was established in 1899, followed by the Constabulary two years later.

Also Read: 8 Dark Chapters of Filipino-American History We Rarely Talk About

The Philippine Constabulary served as the civil government’s police force. Headed by an American officer named Capt. Henry T. Allen, the group’s role was to maintain “public order beyond the capabilities or jurisdiction of the often inefficient native municipal police.”

Its official band, on the other hand, was established on October 15, 1902, and soon started performing in ceremonies and other formal occasions.

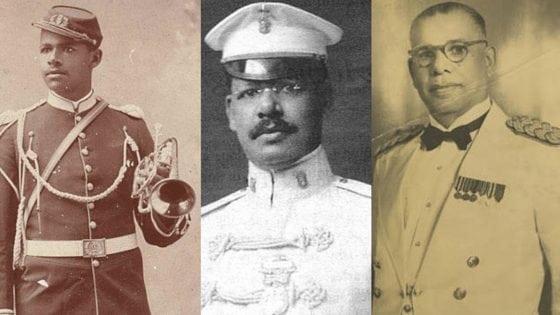

Building this competent group of musicians was a daunting task. It required the help of someone who had the eye for great talents. Someone like the gentleman named Walter Loving.

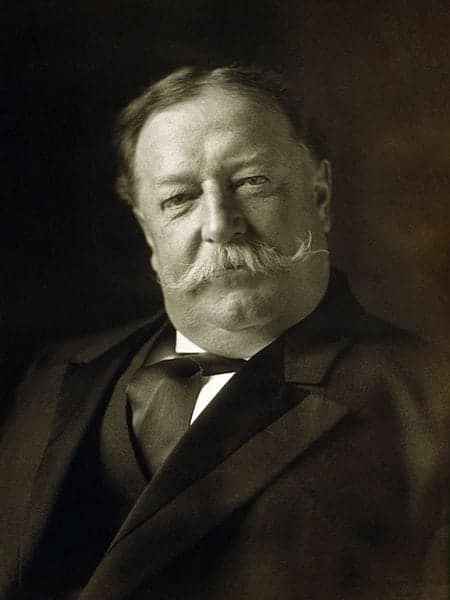

Sometime in 1901, then Secretary of the Philippine Commission William H. Taft was invited at San Fernando to watch the performance of the 48th U.S. Volunteer Infantry band. The black musicians headed by Walter H. Loving impressed the future US president, so much so that Taft approached Loving after the concert to make a promise–that he would make the latter the conductor of a military band once Taft becomes Philippines’ governor general.

Born in Lovingston, Virginia in 1872, Walter H. Loving was the son of former slaves. After his mother died, he stayed in Washington D.C. with his sister Julia, who worked in the household of Theodore Roosevelt, another future US president.

READ: The Adventures of Antero, An Igorot Boy Sensation Who Met President Roosevelt

Loving first enlisted in the Army in June 1893 as a member of the 24th Infantry. When his five-year enlistment expired, he then joined the 8th Voluntary Infantry (1898-1899) and later the 48th U.S. Volunteer Infantry (1899-1901), both of which were black troops assigned in Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War, respectively.

His excellence in music was exemplified when he attended the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music in Boston shortly before serving in the Philippines. However, he didn’t graduate from the institution as he chose to join the Philippine-American War in 1899. Nevertheless, the letter sent by his professor J. Wallace Goodrich says a lot about Loving’s musical prowess.

Intended to convince him to stay in the conservatory, the letter complimented Loving that “during your course of studies…your progress was very remarkable…(The) mark that you attained as a cornet soloist has never been surpassed since this institution organized its special course for the cornet.”

After a brief stint in the Philippines, Loving went back to his home country. In 1902, when William Taft was already a civil governor, Loving was asked to return to the Philippines. Taft stayed true to his promise and made Loving a sub-inspector of the Philippine Constabulary and later the leader of its band.

Forming the Philippine Constabulary Band didn’t come with no challenges. But unlike what most Westerners believed at that time, Filipinos were never the ignorant, head-hunting savages who couldn’t play a single instrument by the time the Americans took over the Philippines. Rather, centuries of Spanish colonization exposed the natives to various European music and instruments.

Therefore, by the time Loving started the auditions to find the best and the brightest talents among Filipinos, many were well-prepared. In fact, most came from a family of band musicians who used to perform in fiestas and important milestones such as marriage or death during the Spanish era, while few were former trumpeters in Aguinaldo’s army.

Among the stand-out talents were Pvt. Pedro B. Navarro, who would later win a bronze medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and become Loving’s first successor in 1916. Born in Ilocos Sur on September 17, 1879, the young Navarro entered the convent of San Agustin in Manila where he was put under the tutelage of master composer Marcelo Adonay.

Excelling both in harmony and violin, Navarro became part of the Philippine Band of Manila, the 29th U.S. Volunteer Band, the 6th U.S. Artillery Band, and the 30th U.S. Infantry Band. He was already a recognizable figure when Loving invited him to become part of the newly-established Philippine Constabulary Band.

Also Read: 8 Filipinos Who Make You Proud To Be Pinoy

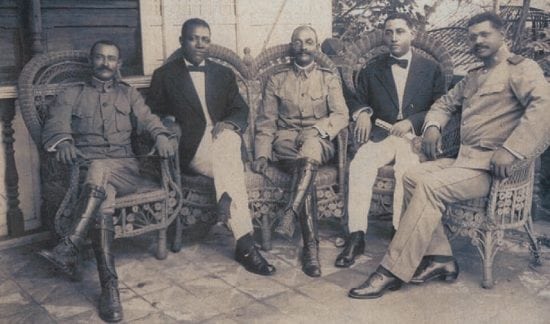

Loving succeeded to convince Navarro and other founding members to become part of his band. His fluency in Spanish certainly helped, so did his reputation as a military figure beloved by many Filipinos. Among other factors, it was probably the common experiences of discrimination and racial inferiority that forged the connection between Loving and the Filipino band.

Thanks to this unifying force, Philippine Constabulary Band was destined for greatness, and there’s nowhere to go but up.

Over the next few years, the band under Loving metamorphosed from a simple band playing ragtime to a more sophisticated group of musicians known for playing symphonic pieces. Their early years saw them performing in outdoor concerts (serenata) first at Binondo Square and later at the more prominent Luneta.

Their first big break, however, came when two American botanists, Dr. William P. Wilson and Dr. Gustave Niederlen, watched them in their first public performance in May 1903. As it turned out, the two were members of the Exposition Board who visited the country to find Filipino representatives for the 1904 World’s Fair at St. Louis, Missouri.

Pleased by the band’s performance, Wilson approached Loving after the concert to give more than just a simple congratulations. The Philippine Constabulary Band was officially part of the world’s fair.

From World’s Fair to a Presidential Inauguration

There’s more to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition than meets the eye. When the Philippine Constabulary Band arrived in St. Louis, Missouri that year to perform in front of thousands of visitors, they were not the only Filipinos at the exhibit.

Joining Loving and his 80 bandsmen were other members of the Philippine Constabulary troops and about 500 Philippine Scouts.

Also Read: The Haunting Story of Filipinos Locked in a ‘Human Zoo’

Clad with decent uniforms and characterized by disciplined behavior, these military men and musicians were placed near other ‘less civilized’ members of the Philippine contingents–the Moros and Igorots. The U.S. Department of War built a 47-acre exhibit to accommodate more than 1, 200 men, women, and children from different Philippine indigenous groups.

In retrospect, these Filipinos unknowingly allowed themselves to be placed inside ‘human zoos’ to accomplish a self-serving goal of the American colonizers. The purpose of the exhibit was clear: to show that America’s “civilizing” power and Pres. McKinley’s “benevolent assimilation” was working.

This became more evident when they intentionally placed the Philippine Constabulary Band near the Igorots whose ‘performance’ at the exhibit ranged from fascinating (reenactment of marriage rites) to downright despicable (dog slaughtering).

READ: From Mountain Boy to Governor: The Incredible Story of Pitapit

But these things probably didn’t bother Loving and the band. Remember, they were the underdogs who generated a lot of buzz after winning awards despite a power interruption that almost derailed their chance to impress the audience.

After their legendary performance of “William Tell Overture” at the exhibit, Loving and the “little brown men” traveled to Louisville, Kentucky for the biennial conclave of Knights of Pythias. In September of the same year (1904), the band also performed at the opening day of Wisconsin State Fair where 20,000 visitors greeted them–the largest crowd to ever show up since the fair was first held.

The band returned to the United States numerous times after 1904, representing the Philippines in 1915 Panama Canal Exposition, where no less than “king of marches” John Philip Sousa dubbed them as one of the world’s greatest; in the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific International Exhibition; and later at the 1939 San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition.

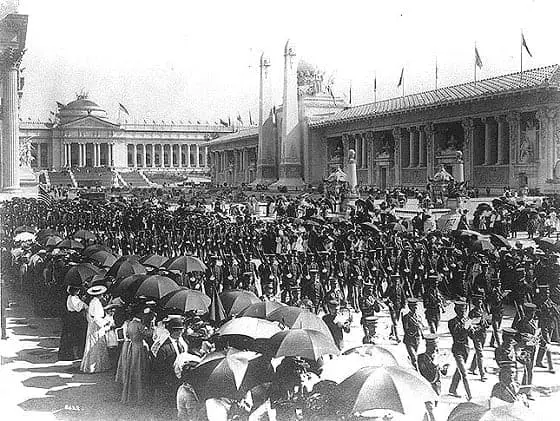

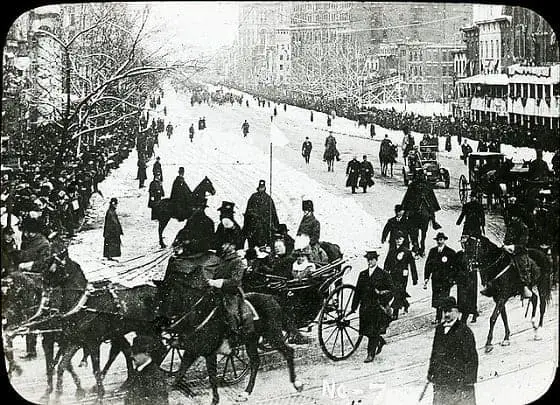

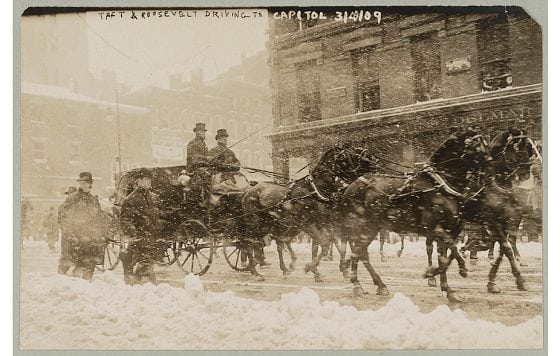

Probably the most memorable, however, was when newly-elected US President William H. Taft invited the band to escort him during his 1909 inauguration.

Also Read: 8 Incredible Rare Recordings From Philippine History

Taft, who had long been a “big brother” to the Filipinos prior to his rise to the presidency, chose the Philippine Constabulary Band to accompany him from the White House to the Capitol, where he took his oath of office on March 4, 1909.

It was the first time in history that a foreign band, instead of the homegrown US Marine Band, served as musical escort to a US president during an inauguration (Philippine Scouts band didn’t lead the procession when it performed in Roosevelt’s inauguration shortly after the world’s fair).

The inauguration took place during the winter season, and it was the first time for the 86-member Filipino band to encounter snow. The medical officer was worried their bodies wouldn’t tolerate the cold climate, but as what Major Gurney (chief surgeon of the Philippine Constabulary) soon found out, no one among the members of the band got sick after performing in the historic event.

A two-day concert was held at the Hippodrome after Taft took his oath of office. The New York Times was all praises to the Filipino band in an article which, just like other news reports from that era, propagated a misconception with its headline:

“Men Who Seven Years Ago Had Never Seen An Instrument Now Play Wagner and Beethoven”

According to the report, the audience who watched the band play “was large at both performances, and showed great enthusiasm.” They performed popular marches and classic opera pieces such as “Stars and Stripes Forever,” “The American Patrol,” “Dixier,” capping it off with the finale performance of “Tannhäuser.”

It went on to praise individual members of the Philippine Constabulary Band, including Pedro Navarro:

“The smallest man in the band beats the snare drum and the way he handles the ebony sticks would make even Miss Fritzi Scheff take notice. His name is San Miguel and his record as a soldier is second only to his ability as a musician. Other players that the band officers always call attention to are Pedro B. Navarro, the piccolo player, who is the chief musician of the band; Hipolito de la Cruz, the star tuba player, who brought out a storm of applause last night when he played Catozzi’s “Beelzebub”; Jose Valaneuva, the finest saxophone player in the Far East, and Jose Potentiano, who was a favorite soloist at the Governor General’s palace in Manila when Taft was the civil head of the islands.”

The Final Bow

As he approached middle age, Loving decided to call it quits. He retired in 1916 due to “total disability” and moved back to Oakland, California. But before he left the country, Loving led a farewell concert at Luneta, after which he received a cup and a watch as gifts from the Filipino bandsmen and the community he served well.

Navarro, the prize-winning piccolo player, took over as the band’s new commanding officer.

Shortly after his return to his home country, Loving tied the knot with Edith McCary, the 20-year-old daughter of an army clerk whom he first met in the Philippines. Their son, Walter Jr., was born in 1917.

Loving again found himself responding to the call of duty when the United States became involved in the First World War. Despite being in his mid-forties, Loving volunteered to become part of the military intelligence section, requiring him to perform surveillance of the African American communities.

Also Read: Meet the only Filipino casualty of the First World War

When his mission was over, Loving and his family sailed back to the Philippines in 1919. Apart from serving the Constabulary Band, he also found a side job as the instructor of the City Boys’ Reformatory band, which he trained in exchange for a salary of 10 pesos a day. He returned to California and secured a job as a realtor and major in the Officers’ Reserve Corps.

The tireless Loving was invited again to go back to the Philippines in the late 1930s, this time to respond to the call of then Philippine President Manuel Quezon to apply his ‘Loving touch’ to the newly-formed Philippine Army band (with which the old Constabulary band was merged).

His last trip back to his home country happened when he and the Constabulary band (now separated from the Army band) participated at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition.

The music of Loving and the Filipino bandsmen came to a bitter halt as the Japanese forces wreaked havoc on the country during WWII. By 1942, thousands of foreigners–including Loving and his wife–were imprisoned at the University of Santo Tomas internment camp.

Also Read: This Unsung WWII Hero Will Inspire You To Be A Better Filipino

Terrible conditions inside the camp took its toll on the aging Walter Loving. His wife Edith had to sell her diamond earrings just to buy Epsom salts–a remedy for Loving’s high blood pressure.

With difficulties also came inspiration: Loving, sick and almost dying, composed a patriotic song while inside the camp. Entitled “Beloved Philippines,” the song leaves an immortal message with the refrain: “We’ll fight for you; we’ll die for you, Beloved Philippines.”

Responding to the plea of some Filipinos, the Japanese allowed the sentence for Loving and his wife to be reduced to house arrest in Ermita. Others then convinced the couple to escape, but Loving didn’t bother to try.

In a 1980 interview, José Baldevarona, a member of the Constabulary band, said that the principled Loving refused to escape because he didn’t want to break the promise he earlier made to report to the Japanese twice a week.

Details of what happened after that are sketchy. It was said that upon the return of the American forces in February 1945, the Japanese prepared to defend Manila until their last breath. In the middle of the bloody conflict, Loving and his wife somehow found a way to reach the shore of Manila Bay. Unfortunately, an enemy soldier separated the two, and Edith ended up in Bay View Hotel along with other women.

Walter Loving was executed, his lifeless body reportedly seen lying at the Luneta–at exactly the same place where he and the Philippine Constabulary Band used to showcase their caliber as world-class musicians.

Edith and her son luckily survived the onslaught of WWII. Edith spent the final decades of her life in California, briefly returning to the Philippines for the Constabulary band’s 50th anniversary in 1952. She died in 1996 at the ripe old age of 101.

Also Read: The Tragic Tale of These Japanese Brothers Will Change How You Picture WWII

Walter Jr., meanwhile, was commissioned as an infantry officer in June 1945, served as an artillery captain during the Korean War, and joined the National Guard until his retirement in 1969. He died in California in 1998, only two years after his mother passed away.

The members of the pre-war Philippine Constabulary Band, mostly forgotten, were among the WWII casualties. Their deaths led to the inevitable disbandment of the group, which later resurfaced after the war as part of the Philippine Army.

Antonino Buenaventura, who would later become a National Artist for Music in 1988, served as the Philippine Army band’s leader for 16 years.

The legacy of the original Constabulary band lives on, and their sudden rise to international prominence remains a timeless source of inspiration.

It’s a story of men who, despite the shackles of colonialism, were able to impress the world and prove that neither color nor race could prevent God-given talents from shining through.

References

Cunningham, R. (2007). The Loving Touch: Walter H. Loving’s Five Decades of Military Music. Army History, (64), 5-20. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/FdNWUe

Hila, A. (2013). Believe it or not, a Philippine band had taken part in a US presidential inaugural.Inquirer.net. Retrieved 24 June 2016, from http://goo.gl/FROQjg

Talusan, M. (2004). Music, Race, and Imperialism: The Philippine Constabulary Band at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Philippine Studies: Historical And Ethnographic Viewpoints, 52(4), 499-526.

Talusan, M. Capt. Pedro B. Navarro, First Filipino Conductor of the Philippine Constabulary Band (1916-1918). MaryTalusan.com. Retrieved 30 June 2016, from https://goo.gl/rhdajW

The New York Times,. (1909). Hearty Cheers for Philippine Band. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/M4AWwm

The Philippine Constabulary Band. HIMIG: The Filipino Music Collection of Filipinas Heritage Library. Retrieved 24 June 2016, from http://goo.gl/fbLMdA

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net