Igorot Headhunters Inside America’s Human Zoos: The Untold Dark Story

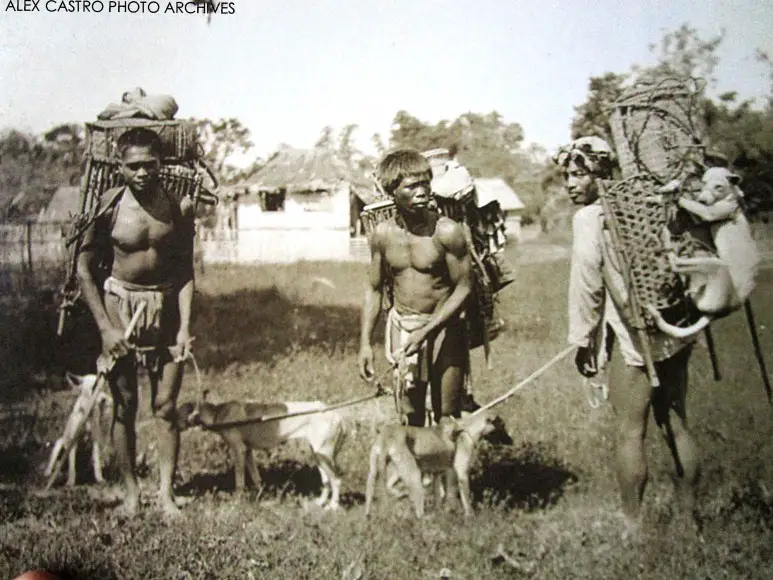

While we’ve known that our ancestors were often looked down upon by their colonizers as dark-skinned uneducated savages, the lowest point of this centuries-old discrimination came in the form of America’s human zoos in the early 1900s. This was when thousands of Filipino tribesmen were taken from their homeland and displayed in exhibits for the American people to gawk at. At these exhibits, the tribespeople—introduced to visitors as primitive dog-eating headhunters to emphasize the US government’s stance that Filipinos were not ready for self-government—was made to live their daily lives in full view of the public. This is their true story.

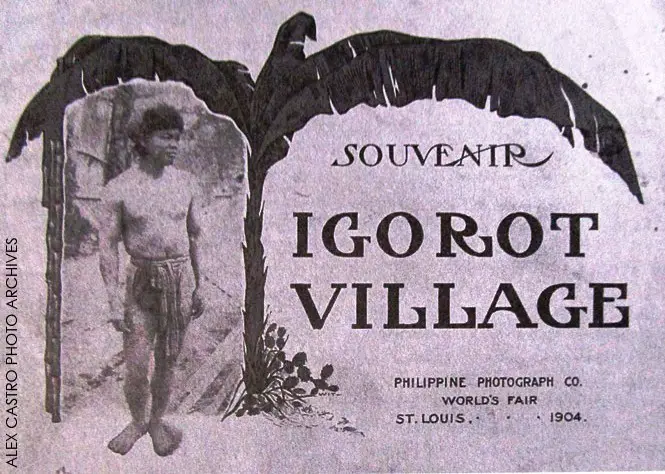

When the gates of the St. Louis World’s Fair closed on December 1, 1904, and the cash in the tills was all accounted for, the fair–which had been attended by close to 20 million people–was declared a historic success, eclipsing the achievements of the previous 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

The monumental event marking the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase drew 43 American states and 60 foreign countries, which put up pavilions and vied for visitors’ attention through shows and exhibits in its 7-month run.

It also became clear which foreign participation attracted the biggest crowd and earned the most revenue. Statistics show that for every 100 fair-goers, 99 people visited the Philippine Reservation, an attraction that overshadowed the other features of the exposition.

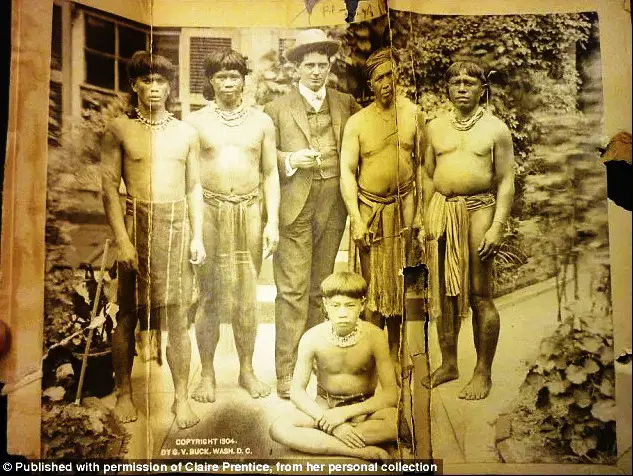

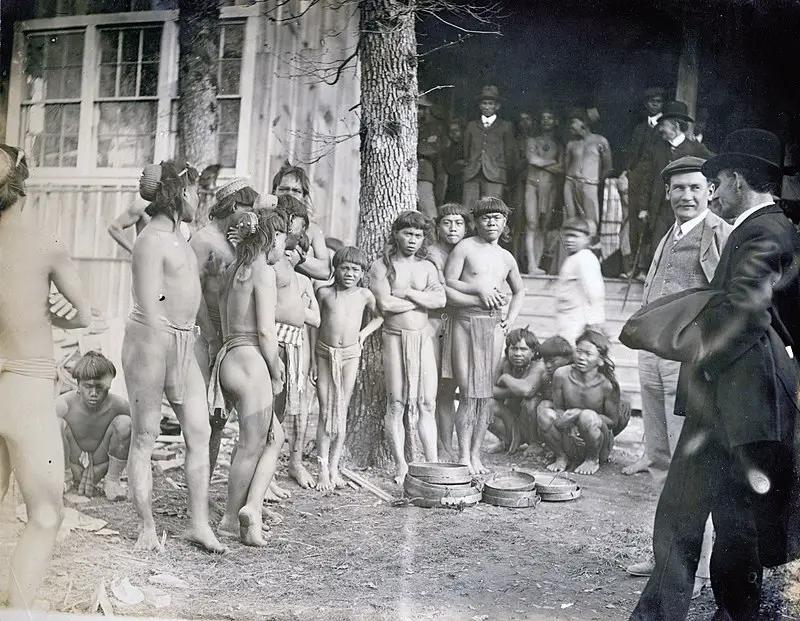

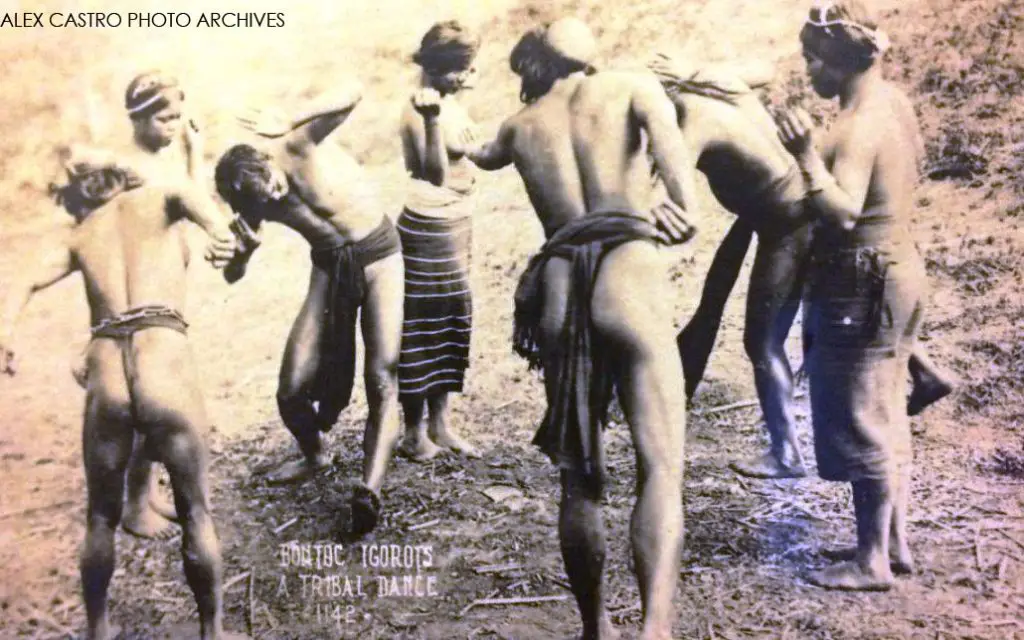

Of the “human zoo” exhibits in the expansive Philippine exhibit grounds, none proved more popular, more controversial, and more challenging to manage than the case of the 72 Igorots who were among the 1,100 Filipino men, women, and children sent to the 1904 fair. Their reputation as “head hunters, cannibals, dog-eaters and black hornets” preceded their arrival, an image masterminded by American imperialist masters, distorted by previous exhibitions and fanned by U.S. media.

Interest in the Igorots for exposition purposes began as early as 1887, when the Exposicion de las Islas Filipinas was staged in Madrid, Spain, with 36 of them, primarily young Igorot braves, were central drawers in the Rancheria de los Igorotes, a village display. A decade later, Igorots made their appearance at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Nebraska and at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, which gathered 100 of the highlanders.

However, the peak of their fame came at the 1904 World’s Fair. Just two months before the fair’s close, receipts from the Igorot Village had amounted to $173,000, an astounding amount at that time. The tremendous financial success generated by the Igorots encouraged many Americans, including those in the government, to conceive ways for the Igorots to remain in America after the end of the fair for their continued exhibition in state fairs, sideshows, and amusement parks.

of the St. Louis World’s Fair.

Philippine Exposition board adviser Edmund Felder, for example, rationalized his proposed 2-year appearance tour of the Igorots in Coney Island and at the 1905 Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition by citing “the general desire on the part of the people of the U.S who did not get to visit the St. Louis World’s Fair to see the Igorots.” In truth, Felder was a master showman and entrepreneur.

Another former Spanish-American war private-turned-impresario was Richard Schneidewind. After being fired from his post office job in Manila in 1901 for being part of a smuggling ring, Schneidewind, who was briefly married to a Manila girl, shifted to the more lucrative career of recruiting tribal people for supposed anthropological and ethnological exhibits. Indeed, his sources in the Philippines were plentiful.

The ringleader of this cabal was the master of deceit, Dr. Truman K. Hunt (1866 – 1916). As a doctor, he joined the American medical corps and was sent to the Philippines in 1898 at the onset of the Spanish American War. He stayed on after the Philippine cession to America, and the audacious doctor spent much time in the northern highlands prospecting for gold in Abra in 1900.

Hunt found his way to Suyoc and Bontoc, where he led vaccination programs among Bontoc Igorots, who gave him their trust and friendship. As a reward, Hunt was named Lieutenant General of Lepanto-Bontoc province.

Philippine reservation, at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

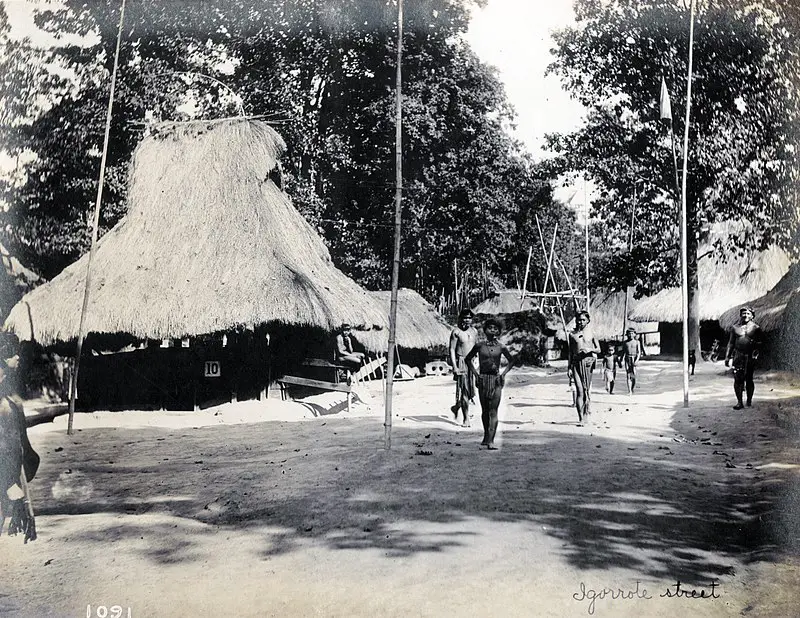

Because of his familiarity with the natives, Hunt was appointed a manager of the Igorot Village at the 1904 World’s Fair, populated by Igorots from three different areas—Bontoc Igorots, Suyoc Igorots, and the Tinguianes from Abra.

As the fair drew to a rousing close, Hunt saw the enormous potential of the Igorots as stars of his planned ethnological show business. He had sent feelers to Henry Dorsch, director of the Lewis & Clark Centennial and American Pacific Expo and Oriental Fair, to include Igorots in the fair, scheduled to open in 1905.

It was a vision shared by Felder, whom Hunt partnered with to form the International Anthropological Exhibit Co. But differences arose between the two, as Hunt wanted Igorot-only shows.

Overnight, Hunt went from being a protector of the Igorots to a greedy exploiter. Felder found a new partner in Schneidewind, and a contentious rivalry began.

Beforehand, however, the Philippine Exposition Board had received alarming reports that “certain person, anxious to gain fame and fortune as showmen, had induced some of the Igorots to remain in the U.S.” These unscrupulous persons had hoped to file a habeas corpus to legitimize their extended stay in the U.S.

However, the Igorots were technically wards of the state; they could not be made to decide for themselves. To safeguard the Igorots from these dubious people and to avoid court actions that might keep them in the U.S., they were quickly spirited away on the eve of the closing of the St. Louis World’s Fair.

But Hunt was not to be deterred; he had an inside track of running circles around government processes and still wielded influence among the highlanders he once governed.

While onboard the Philippine-bound ship with Igorot returnees, he struck up a deal with his assistants to round up 50 Igorots in Bontoc, dangling a $ 15-a-month salary for the recruits. Under his new company, the Igorot Exhibit Co., Hunt had mapped out a plan to feature them in a series of “cultural shows” in amusement parks, beginning with the famed Coney Island in New York.

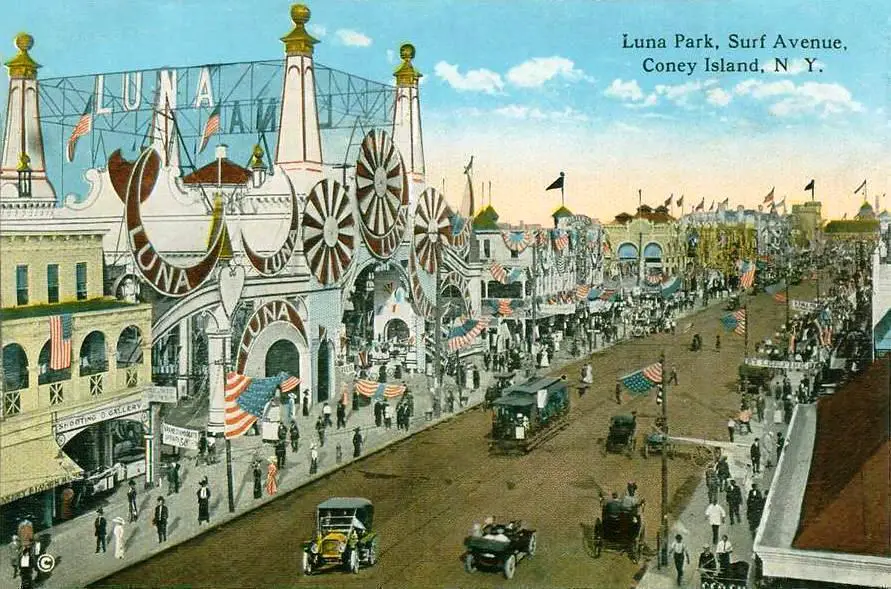

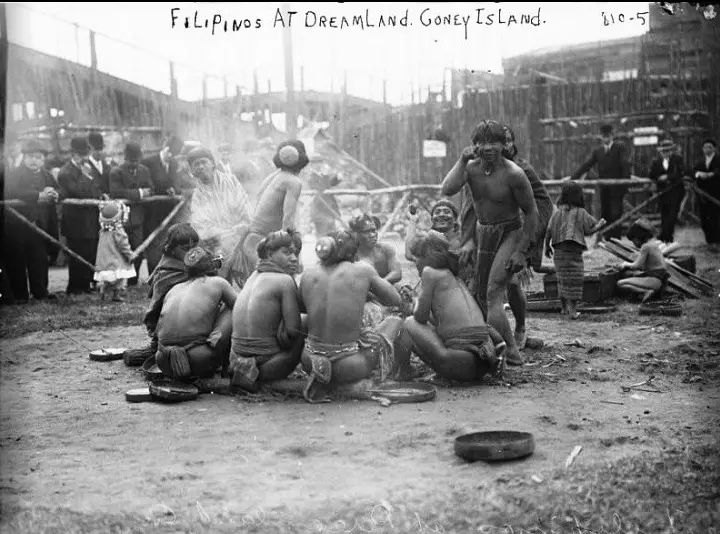

Coney Island was once a seedy amusement place in Brooklyn, with the opening of its first enclosed attraction, the Sea Lion Park, in 1895. From 1897 to 1904, Coney Island was transformed into a beautiful beachfront resort, a technologically sophisticated entertainment center that found wide patronage from people of all social levels.

Of its cluster of entertainment places, Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland were the most popular. Coney Island earned nationwide renown as well as many monickers, including “America’s Playground,” “Nickel Empire,” “Poor Man’s Paradise” (for its affordable attractions), and “Electric Eden.”

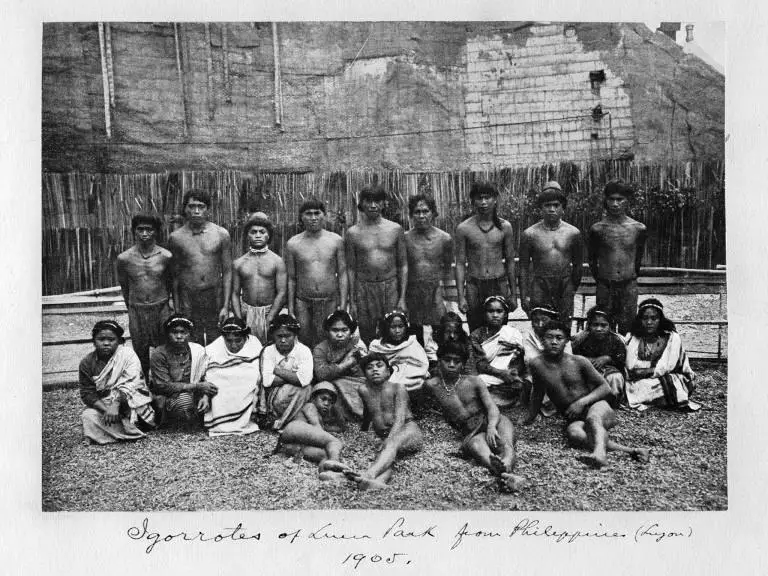

On May 15, 1905, Truman Hunt herded his scantily-clothed Bontoc Igorots and an interpreter to Coney Island, preceded by media hype like no other. Hunt had fed the press of the bizarre customs of these “wild, head-hunting, dog-eating savages” from the mountains of the Philippines, and these made sensational daily, keeping the public shocked, awed, and entertained.

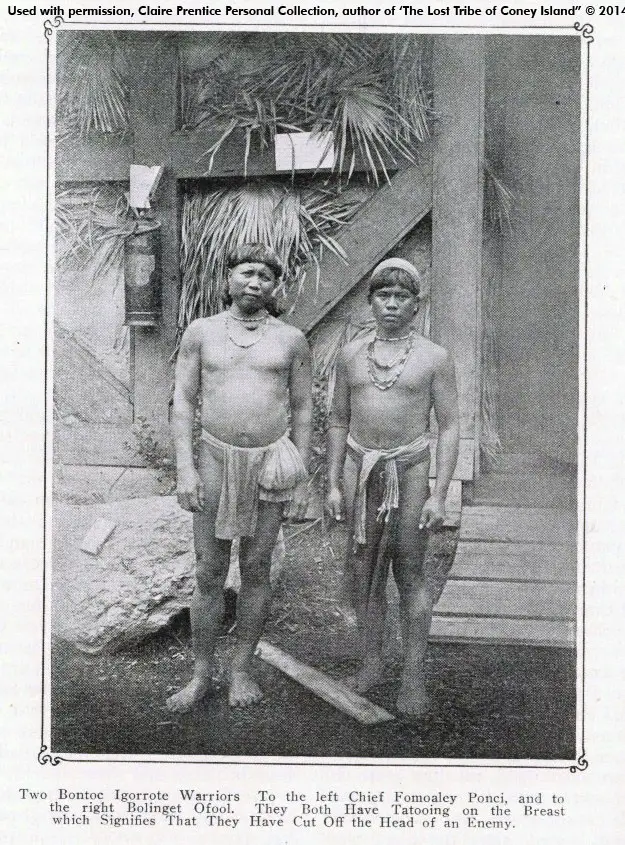

Newspapers had a heyday as they described the men “who looked the part of head-hunters with a vengeance.” They took note of the bodies of the men and women “tattooed from head to foot, the marks on the chest of some of the men indicating… that they were fully-fledged harvesters of heads”.

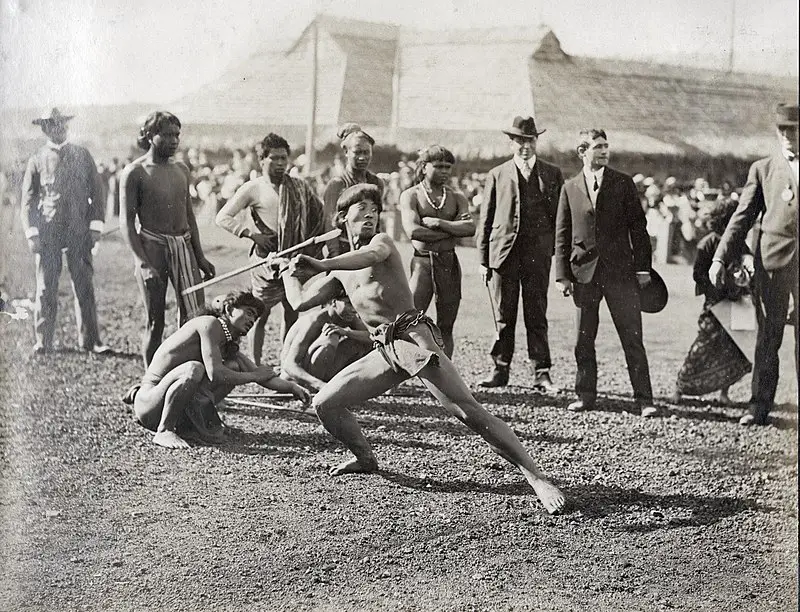

Americans came in droves to Luna Park every day and paid 25 cents to watch the Igorots as they staged shows in their makeshift village that often involved ritual dancing, chanting and singing, sham re-enactments of warrior fights, weddings, funerals, and of course, dog feastings (the canines were supplied by local pounds)–anything to highlight their primitive otherness.

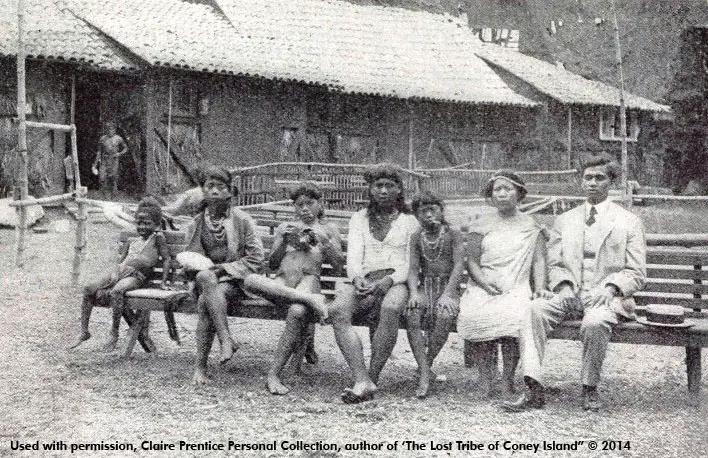

Some of the names of these Igorots have come down to us, as researched by Claire Prentice, author of the “Lost Tribe of Coney Island,” the book that followed the journey of these mountain people in America’s sideshow circuit.

There was Fomoaley Ponci, the portly tribal chief of the group who likes to give interviews and can be chatty with the press. Bontoc-born, he had four brothers and a sister and grew to become a headhunter before he got married.

Fomoaley’s life story was included in a book, “The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans, As Told by Themselves,” published in 1906. He remembered enduring his travel to Brooklyn:

“We were carried for many days in houses that went on wheels and flew like birds. And now it seemed the land would never end. We must have come nearly a hundred days’ journey in a week. But at last, we reached another big water again, and then we stopped on the shore of this great city of Coney Island”.

In one staged presentation, the Igorot chief shocked the audience by killing a chicken with a stick, burning its feathers, and sprinkling its blood on their huts. The American Humane Association raised a furor over the killing of the bird, only to be appeased by Truman, who explained its religious significance, a sacred way to remember the death of a senior tribe member in Seattle.

Then there was Bolinget Ofool, a headhunter admired by visitors for his intricately-tattooed body. Feloa was another popular Igorot who had left Bontoc to earn money for his family. Dengay, Feloa’s friend, also went for the same purpose—to provide for her three children. The two would later offer damaging information about Hunt’s shenanigans.

There were children in the group, and the most articulate was Tainan, a 9-year-old English-speaking Bontoc boy who could sing patriotic songs in English. Like his more famous counterpart and star of the St. Louis show, Antero, Tainan regaled the audience with his big voice and facility with the foreign language. When he returned home, he would assist the Rev. Hillary Clapp in compiling words in the Bontoc language for the missionary’s dictionary project published in 1908.

Tainan was a friend of a Negrito boy with the fanciful name Friday Strong. He was adopted and cared for by Maria Balinag, the 18-year-old Igorot wife of the translator, Julio Balinag.

Julio Balinag had also been an interpreter for the Igorots at the World’s Fair the year before, where he received a bronze medal for his services. He was the son of an Ilocano soldier and a Bontoc woman, and a brother of Nicasio Balinag, who became Bontoc’s deputy governor.

A former constabulary office, interpreter Balinag could speak Ilocano, Tagalog, Spanish, and English, aside from the Bontoc language. He would prove to be a crucial figure in unmasking Hunt as a corrupt and duplicitous manager.

Without the Bureau of Insular Affairs’ knowledge, Hunt had been “importing” more Igorots for shows he had contracted to stage in fairs and amusement parks across the U.S. The government was slowly losing management control to private individuals, and Hunt’s roadshows—totaling over 50 between December 1905 to February 1906- quickly confirmed officials’ worst nightmare.

With Igorots so coveted, piracy of tribesmen became rampant. There have also been reports of serious grumbling among Igorots about shoddy living conditions, low pay, and deception.

The unmasking began when Hunt took his Igorot troop to Sans Souci amusement park in Chicago. Whether intentional or coincidental, Schneidewind and Felder also staged their show in nearby Riverview Park.

The partners would not allow a head-to-head competition, especially with their leading rival, so they reported Hunt and asked for federal inspection of the competing operations, asserting that Hunt’s inferior exhibit might mislead people into thinking it was their Filipino Exhibit Co, show.

In the past, Hunt had evaded inspection by shuffling the Igorots from place to place, but there was no escape this time.

Library of U.S. Congress.

The following inspection shocked the federal authorities: while Schneidewind and Felder’s were legal and humane, Hunt’s operation was declared “illicit and atrocious.”

The report described the eighteen Igorots in the show as living in three small tents beneath a noisy roller coaster, without privacy, and in filthy surroundings.

But the worst accusations were hurled at Hunt when the Igorots began complaining about his financial chicanery. Reports indicated that they were abused and embezzled US$15,000 by the end of their exhibitions. Hunt countered that he was safeguarding their earnings by keeping their money.

Suspicions had been rife after the 1904 World’s Fair when Hunt was confronted by Carson Taylor, a banker named to handle the accounts of the Igorots. When asked to turn over their funds, Hunt replied there were none. Like Felder, Hunt believed “that the Igorot, as an individual, has no need of money.”

Still, the sly Hunt eluded the authorities from taking his prized Igorots away. Since processing their papers and arranging their trips back to Bontoc takes time, Truman jumped at the opportunity to start hiding the Igorots and spiriting them away.

In the end, Hunt succeeded in sending the Igorots to nearby Canada and scattering them around the U.S. at state fairs, thus eluding authorities who had wanted to send them back to the Philippines.

The results of the U.S. War Department’s investigation, plus the corroborative complaints of Igorots, resulted in the filing of suits against Hunt in 1906 in Chicago, New Orleans, and Memphis. Julio Balinag and several Igorots provided testimonies proving the accused’s guilt.

In Memphis, where 2 cases were filed, Dengay and Feloa recounted how Hunt systematically stole their money. The jury ruled in favor of the Igorots, and Hunt was convicted and sentenced to eleven months and twenty days in the first Memphis case and six months of hard labor in the second. Some money was recovered and returned to the Igorots.

In February 1907, however, Hunt was freed after a mysterious judicial reversal, in which the case was declared a mistrial. While he had served eight months in prison, the New Orleans case was still to settle, but he had disappeared.

The fugitive’s escape was said to have been planned in connivance with the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks, a fraternal club that Hunt had helped by showing his Igorot exhibits in their fund-raising programs.

After 1907, private businessmen and the Bureau of Insular Affairs became more versed in the shows’ operations involving Igorots, which persisted from 1908 through 1911. Exhibitions were held indoors in the U.S. and Europe, and a tracking system was put in place by the U.S. government to monitor the location of their wards. Contracts also were drawn that stipulated wage increases over time.

For a few more years, the Igorots continued to make appearances in Coney Island, who, along with Native Americans, “giants,” “Lilliputian men and women,” “3-legged people,” and Siamese twins, filled a niche in the entertainment industry for the strange, the unusual, and the bizarre in the form of “living wonders.”

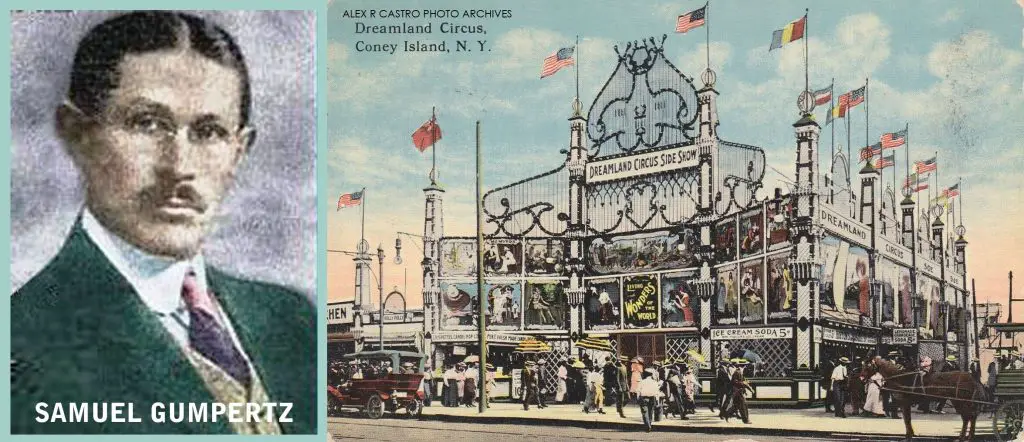

American showman Samuel W. Gumpertz, manager of Dreamland and founder of “The Congress of the World’s Greatest Curiosities,” traveled all over the world looking for Igorots to exhibit, together with his “Wild Man of Borneo” and the platter-lipped women of Ubangi. Former Philippine Constabulary captain and teacher John R. McRae took a band of Igorots to the East Coast in 1908, ending in a summer show at Coney Island in 1909.

After that, the showmen felt the effects of tighter government controls as emigration became stricter; even the well-connected Schneidewind had difficulty getting permission to bring Igorots for a European exhibition in 1911. The opposition from the Philippines, which, from the start, had vehemently objected to the display of minorities representing the nation at foreign expositions, was reaching a fever pitch.

Former governor William Cameron Forbes had called 1904 fair “a great social and political injustice” that created an “objectionable impression.” In Manila, the influential paper, La Igualdad, condemned the exhibit of any Filipinos, Igorot or not.

Eventually, too, living in America and the rigors of traveling roadshows took their toll on Bontoc Igorots. Plagued by sub-zero temperatures, diseases, and starvation, some Igorots died, like the nine abandoned by Schneidewind in Ghent, Belgium, in 1913.

As to the natives brought by Truman Hunt to Coney Island, the novelty and thrill of going to America wore off as the harsh realities of their participation in shameful shows run by abusive masters became more apparent.

Sporadic demands for Igorot shows persisted as late as 1931 when the U.S. government wanted them for display at the Paris Exposition. Only at the 1958 Brussels Universal Exposition in Belgium did the practice of exhibiting human beings end.

In retrospect, Chief Fomoaley mused, “I have seen many wonders here, but we will not bring any of them home to Bontoc; we do not want them there. We have the great sun and moon to light us; what do we want your little suns? The houses that fly like birds will be of no good to us…This is a fine country, and I like all the people, but I am going back to Bontoc to stay there till I die.”

And returned he and his companion Igorots did, back to the highlands of Bontoc, where village mates admiringly called them “Nikimalika” (naka-Amerika, those who have experienced America), bringing with them stories and souvenirs of their sojourns and where they slowly settled back into their lives of quiet and obscurity.

References

Afable, Patricia O. Journeys from Bontoc to the Western Fairs, 1904-1915: The “Nikimalika” and their Interpreters, Philippine Studies, Vol. 52, No. 4, World’s Fair 1904 (2004), pp. 445-473. Ateneo de Manila University.

Fermin, Jose D. 1904 World’s Fair: The Filipino Experience, (2004), The University of the Philippines Press, Q.C.

Hamilton, Holt. Ed. The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans As Told By

Themselves, (1906), “Story of an Igorrote Chief,” p. 225-233. James Pott & Co., New

York. https://archive.org/details/lifestoriesundis00holtrich/page/236/mode/2up

McCullough, Edo. Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey into the Past © 1957/2003. Fordham University Press, NY.

Pilapil M.D, Virgilio R. Touring the Legacy of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, research collaboration by Alfred J. Katzenberger, Jr. (2004). The House of Isidoro Press.

Prentice, Claire. “The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man

Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century,” (2004). Amazon Publishing/New Harvest.

Prentice, Claire. The Igorrote Tribe Traveled the World for Show And Made These Two

Men Rich. smithsonian.com. 14 Oct. 2014. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/igorrote-tribe-traveled-world-these-men-took-all-money-180953012/

Qiu, Linda, Tribal Headhunters on Coney Island? Author Revisits Disturbing American

Tale, published 28 October 2014, National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/10/141027-human-zoo-book-philippines-headhunters-coney-island/

Sanjek, Roger ed., Mutuality: Anthropology’s Changing Terms of Engagement, p. 102,

University of Pennsylvania Press, (2004)

Thomson, Rosemarie Garland, ed. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary

Body, “Ogling Igorots: The Politics and Commerce of Exhibiting Cultural Otherness

1898-1913)” by Christopher Vaughan, Chapter 4, section 15, (1996) New York University

Press, N.Y.

Alex R. Castro

Alex R. Castro is a retired advertising executive and is now a consultant and museum curator of the Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, Angeles City. He is the author of 2 local history books “Scenes from a Bordertown & Other Views” and “Aro, Katimyas Da! A Memory Album of Titled Kapampangan Beauties 1908-2012”, a National Book Award finalist. He keeps 2 pop culture blogs: “Views from the Pampang” (2009 Philippine Blog Awards finalist) and Manila Carnivals 1908-1939. He is a 2014 Most Outstanding Kapampangan Awardee in the field of Arts. For comments on this article, contact him at [email protected]

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net