10 Weird Phenomena That Perfectly Sum Up Today’s Filipino Culture

Every country in the world has its own range of social phenomena which makes its culture unique; in the Philippines, it’s the same as well.

With such a diverse demographic, it’s no wonder so many social phenomena abound in the country and which give us our unique Pinoy identity. And as we are about to find out, these social phenomena make the Philippines the country it is today—without them, Pinoy culture just wouldn’t feel the same anymore.

Also Read: 12 Annoying Attitudes of Filipinos We Need To Get Rid Of

10. The “My Way Killings.”

While the Philippines is not the only karaoke-crazy nation on the planet, only it can lay claim to a crime so bizarre it’s known internationally as the “My Way Killings.” Specifically, singing Frank Sinatra’s timeless classic has a higher chance of igniting a barroom brawl (and an early death) than any other song.

Related Article: Who Invented The Karaoke Machine?

So what makes “My Way” such an accursed song? Explanations have ranged from the song’s arrogant lyrics to its own popularity. According to pop culture authority Roland B. Tolentino of the University of the Philippines, the song itself acts as a trigger for a culture predisposed to violence whenever social rules are broken.

Simply put, violence will happen whenever there’s a breach of karaoke etiquette (hogging the microphone, singing a song badly, laughing or jeering). Add the self-indulgent lyrics of “My Way” plus its higher probability of being sung in a bar, and you have a recipe for disaster.

9. The Aswang Phenomenon

If there has to be a national bogeyman, it would have to be the aswang. As we’ve discussed before, the Spanish successfully utilized the natives’ own folklore against them by equating the aswang with the once-revered caste of babaylans.

During the Spanish period, the image of an aswang became heavily “Westernized” with horns and wings attached to reflect the European version of the devil. In Capiz—the so-called home of the aswang—the lack of understanding by foreigners and locals over the endemic disease X-linked dystonia Parkinsonism (known as “lubag” in the vernacular) also contributed to the aswang myth. In time, virtually every area controlled by the Spanish had its own version of the aswang.

READ: 9 Pinoy Historical Villains Who Weren’t As Evil As You Think

As to why the myth of the aswang remains so prevalent even today, it now has something more to do with a concept rather than an actual monster. As stated in the documentary by Canadian filmmaker Jordan Clark, a town with lots of problems would attempt to turn them into a real, tangible object which it could defeat, thus providing townspeople with a sense of unity and healing. In this case, the perfect personification would be the aswang.

On the national level, Filipinos equate aswang with the country’s social evils—a practice that goes back to our ancestors’ original folklores which treated the aswang as more of a symbolic social evil which harms the people rather than a real monster.

8. The Querida Syndrome

While it is indeed a country-wide cultural practice which encompasses practically every demographic, it is interesting to know Filipino men’s penchant for keeping No. 2s did not originate with the Latin machismo culture brought by the Spanish.

Also Read: The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in Philippine History

Before their arrival, the natives heartily practiced the art of concubinage. In fact, each ethnic group even had their own terms for a mistress; for example, the Tagalogs called them “kalunya, kaagulo, or kaapid.” Although the Spanish attempted to dissuade the practice, they too soon indulged in it, creating the terms “despensera” and “kerida.”

With the arrival of the Americans, the practice of keeping a mistress became even less frowned upon. No wonder keeping a mistress is impliedly accepted among male Filipinos in spite of the country’s strong Catholic upbringing—it’s been practiced for centuries and is unlikely to go out soon.

7. The Pacquiao Phenomenon

A phenomenon with a no-brainer explanation, this happens every time “Pambansang Kamao” Manny Pacquiao fights.

Due to his overwhelming popularity, practically every Filipino in the country is glued to a screen every time Pacquiao fights. Streets are clear and traffic is non-existent. Even better, crime rates practically drop to near-zero percent, as even criminals stop whatever they’re doing to watch Pacquiao fight.

The same goes for insurgent activities as well, as communist and Moro guerrillas would temporarily lay down their arms to watch a Pacman bout. In short, virtually every activity in the Philippines comes to a grinding halt whenever Pacquiao fights—a testament to his popularity.

6. The Filipino Ability To Smile During Disasters

If the Japanese are disciplined during disasters, then the Filipinos are happy go-lucky. We have proven it so many times in the face of disasters, especially with floods as the Philippines happens to be a typhoon magnet. Even though our homes are flooded and our properties are destroyed, we will just smile away and laugh (and make countless memes). By extension, we smile and laugh at our personal, social, and economic troubles.

Just how do Filipinos in general cope up with life’s problems? The answer lies of course in the national psyche, known as the “Bahala na” or fatalistic attitude. As we’ve discussed before, Filipino fatalism can be double-edged; while it resigns a Filipino to his fate, it also gives him the strength to endure.

In cases of troubles and disasters, “optimistic fatalism” gives Filipinos the resiliency they need to survive in the belief that such problems will eventually go away. And as we have seen, this good kind of “Bahala Na” has served Filipinos well countless times already.

5. The Tingi-Tingi Phenomenon

It is said no bonafide Filipino community would be complete without a sari-sari store. Said to have started as early as 1127 AD when Chinese from the Sung dynasty would frequently barter with the natives, the sari-sari store has been a timeless fixture of Filipino culture.

However, the “tingi-tingi” or sachet phenomenon really went off during the 1990s when manufacturers began the trend of “downsizing” in response to the troubled economic times of that period. For low-income Filipinos, the practice of buying by sachet meant they could still satisfy themselves with a product even though they had less money.

READ: 9 Philippine Icons and Traditions That May Disappear Soon

The practice also serves practical purpose as far as choice as concerned as it gave the customer a wider latitude with which to choose his products at low cost. Lastly, the practice of buying tingi-tingi has also been spurred with the Filipino belief that products in smaller amounts are more concentrated and hence pack more value than one bought at wholesale.

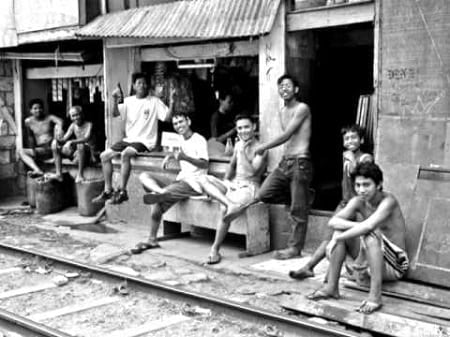

4. The Istambay Phenomenon

Believe it or not, there really is such a thing as an “istambay phenomenon” and is unfortunately prevalent among Filipino youth (especially males). And contrary to popular belief, istambays are not neighborhood toughies too lazy to get a job as we often like to stereotype them.

As concluded by sociologist Clarence Batan in his exhaustive research into the phenomenon, the lack of socio-economic opportunities, the inability of government to fully address social problems, and the close familial ties prevalent in Filipino culture all contribute to the proliferation of istambays in the country.

Recommended Article: 9 Extremely Notorious Pinoy Gangsters

While the first two are self-explanatory, the third one is a bit surprising. However, as Batan discovered, the closeness of a typical Filipino family provides sustenance and shelter for the istambays, allowing him to survive his joblessness. As a result, his transition to independent adult living is severely delayed or even brought to a permanent standstill.

3. The Filipino Text Messaging Phenomenon

As the perennial “Texting Capital Of The World,” Filipinos have sent out more than a billion text messages daily since 2008. Being more affordable and faster than the traditional modes of communication, text messaging quickly caught on with the Filipino public. The phenomenon even gave rise to the sub-culture known as “Generation Txt” whose adherents have developed their own unique language.

Aside from being a product of the Filipino practice of “tingi-tingi,” texting’s popularity is also reflective of the typical Filipino’s preference for non-confrontational communication. According to sociology professor Josephine Aguilar, the art of texting provides Filipinos a convenient vehicle with which to express themselves things that could not normally be said easily face-to-face.

Simply put, texting allows Filipinos to overcome their shyness or “hiya” which is deeply embedded in the Pinoy psyche—and which might also explain why courtship is done through text these days.

2. The Filipino Social Media Phenomenon

Aside from being big fans of texting, Filipinos also love being online, so much so that we have also earned the title of “Social Networking Capital of the World.”

Just like with texting, social media affords Filipinos a measure of privacy they need to express themselves without being confrontational and allows family members and friends to keep in touch despite the distance. Additionally, social media resonates well with the Filipino concept of “kapwa and pakikisama” since we are generally a very social people. It is also in line with the Filipino’s inclination towards close family ties.

In short, social media provides Filipinos the opportunity to break physical barriers and form a giant family and community composed of Filipinos—an online barangay, so to speak.

1. The Filipino Teleserye Phenomenon

Why do Filipinos love teleseryes, so much so Ateneo is even offering a course dedicated exclusively to the study of Pinoy soap operas. The answer is simple: teleseryes are a microcosm of Filipino society at large.

According to Ateneo pop culture professor Louie Sanchez, Filipinos are drawn to teleseryes mainly because they can relate to the personal, social, and political issues repeated so often in the genre. In spite of having far-fetched, tacky or clichéd plots from time to time, teleseryes really reflect life in the Philippines which Filipinos can empathize with. And the good thing about teleseryes is that they are constantly expanding their repertoire to include a wider audience demographic—even the upper classes are now into teleseryes.

Also Read: 9 Signs You’re Watching A Pinoy Soap Opera

Another sociologist, Ricky Abad, had this to say why Filipinos love teleseryes: “it’s a country that simply loves a good story-telling.” Indeed, Filipino fascination for teleseryes has spread to other countries, from its nearby Southeast Asian neighbors to countries in the African continent.

References

Aquino, T. (2014). On first day of Teleserye class, Ateneo prof says everyone watches soaps.InterAksyon.com. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/44MHqX

Business Wire,. (2010). Research and Markets: Philippines – Telecoms, Mobile and Broadband. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/9sLdth

Olarte, A., & Chua, Y. (2005). Mini-size me. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/8dDoDA

Onishi, N. (2010). Sinatra Song Often Strikes Deadly Chord. The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/d8DtSW

Rappler,. (2013). Filipino humor persists in times of disaster. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/PtkWtp

Tariman, P. (2014). The perks and lures of teleserye. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/ZyQjnE

Turcotte, L. Clarence Batan: Giving a voice to Filipino Youth. International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/mImdKv

Villegas, R. (2012). From ‘despensera’ to ‘No. 2’: A history of mistresses in the Philippines.Inquirer.net. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/pXhPsX

Yahoo!,. (2014). Research Confirms: The Philippines is Still the Social Media Capital of the World. Retrieved 17 July 2015, from https://goo.gl/nvzXSu

Additional Sources

Mobile Phone Cultures by Gerard Goggin

Deep Control: Essays on Free Will and Value by John Martin Fischer

Psychologic, Anthropological, and Sociological Foundations of Education (Foundations of Education 1) by Alicia S. Bustos, Ed. D., Socorro C. Espiritu, Ph.D.

Understanding Filipino Values on Sex, Love and Marriages by Tomas Quintin D. Andres

The Inside Text: Social, Cultural and Design Perspectives on SMS by R. Harper, L. Palen, A. Taylo

Cell Phone Culture: Mobile Technology in Everyday Life by Gerard Goggin

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context by Uichol Kim

Dubbing and Subtitling in a World Context by Gilbert Chee Fun Fong

The Pilot Food Price Subsidy Scheme in the Philippines: Its Impact on Income, Food Consumption, and Nutritional Status by Marito Garcia, Per Pinstrup-Andersen

Secondary Sports Assemblies: 40 Sport-themed Assemblies to Inspire and Engage by Brian Radcliffe

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net