The Oldest Known Photos of the Philippines Ever Taken

Located in the lower Washington Heights area in NYC, the Hispanic Society of America is a century-old institution often mistaken for sports or social club because of its name. No less than The New York Times described it as the “most misunderstood” place in the city.

Notwithstanding its weak efforts to attract more visitors, the HSA is a museum-cum-research library where one can find world-class paintings by Goya, Velázquez and El Greco, just to name a few.

Also Read: The Way We Were: Rare Color Photos of the Philippines in the 1950s

For Luisa Casella and Rosina Herrera, however, what they discovered here in April 2007 are more memorable than most things displayed in the museum.

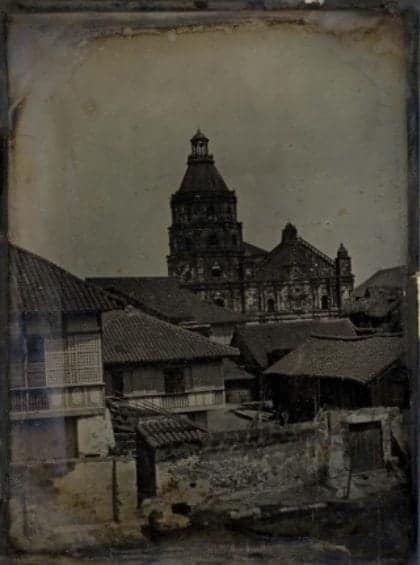

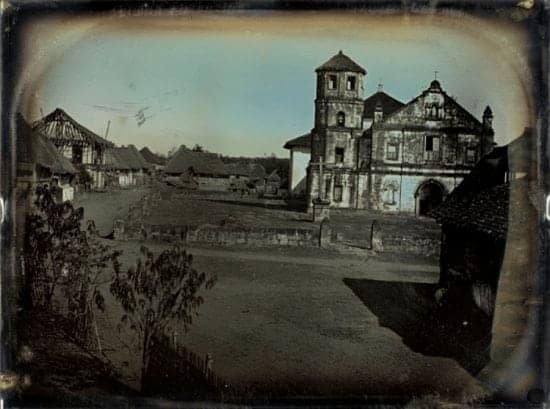

Tucked away in a cabinet at the 7th floor of the building were a group of 18 rare daguerreotypes of Manila from the 1840s, possibly the oldest photographic record of the Philippines ever discovered.

At that time, Casella and Herrera were both Andrew W. Mellon Fellows from the Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation (ARP). Their original plan was to rummage HSA’s photo collection and preserve what’s left.

Things turned into a different direction when they found the Manila daguerreotypes inside a cardboard box.

Composed of 13 whole plates and 5 half-plates, the photos show incredibly preserved views of Manila, Marikina and Laguna never seen before by the public. Aware of the very nature of these early photographs, they soon embarked on a painstaking project to prevent the artifacts from suffering permanent damage.

To accomplish the mission, they sought the help of the oldest museum dedicated to photography–the George Eastman House. The latter’s Photograph Conservation Department worked closely with different conservation scientists, putting all the work for 18 straight months just to ensure the housings and the photos themselves would be in tiptop shape.

The results, thankfully, are nothing short of remarkable.

Daguerreotypy 101

A daguerreotype is the great granddaddy of modern-day photographs. It was named after the Frenchman Louis Daguerre who, in 1838, took a photo of a Parisian having his shoe shined.

The said picture, possibly the first in history to ever feature a human being, was produced using an early process pioneered by Daguerre himself.

In this system, particulates of silver, mercury, and gold were formed on the surface of a silvered copper plate.

Daguerre’s camera required exposure times that could last as long as 15 minutes or so. Now you know why portraits from long ago have subjects who didn’t bother to smile.

It may have achieved a milestone but Daguerre’s photo doesn’t hold the distinction of being the first daguerreotype in history. That honor belongs to a picture taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, one of Daguerre’s partners.

This oldest surviving photograph, estimated to have been taken either in 1826 or 1827, shows a view from Niépce’s upstairs window at his estate in Le Gras, in the Burgundy region of France.

Also Read: Fantastic 116-Year-Old Color Pictures of the Philippines

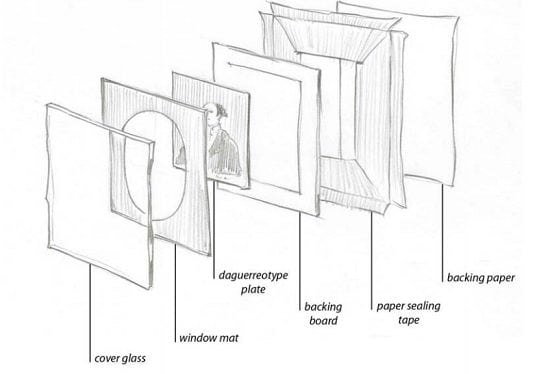

Daguerreotypes are extremely sensitive, so much so that surface contact or even air pollution could render these photos permanently damaged. This is why as soon as the pictures were formed, pioneer photographers put them inside tightly sealed housings.

The daguerreotype housings are of two kinds: the French style and the British/American style.

Upon their discovery, the Manila daguerreotypes were enclosed in French style housings, also known as passe-partouts. Now, in order for them to estimate how old these pictures are, the experts looked at various elements, which included the features of the said housings.

In a detailed report by fifth cycle fellow Caroline Barcella of the Conservation Department at George Eastman House, she discussed that a typical French housing from the early 19th century consists of “a cover glass, a window mat, and a backing board bound together with paper sealing tape.”

From the early to late 1840s, the trend was to use a reverse painted cover glass which also served as the window mat. After that, a thick slanted mat was added just beneath the reverse painted cover glass.

Also Read: 20 Remarkable Colorized Photos Will Let You Relive Philippine History

Among the Manila daguerreotypes discovered, most have “reverse painted glass with an octagonal window opening” while others either have missing cover glass or a painted glass with a beveled mat.

Judging by the style of the housings and the photographic process used to produce these pictures, it can be said that the Manila daguerreotypes were taken from the early 1840s to the early 1850s.

Another element that the scientists looked into was the logo of the plate maker. Fifteen of the daguerreotypes discovered share the same logo–a six-pointed star–which suggests that they came from the same plate maker.

As for his identity, the conservation scientists had only one person in mind: Jules Alphonse Eugène Itier (1802-1877), the plate maker of the pictures displayed at the exhibition “Paris et le daguerreotype.” The said daguerreotypes bear the same “six-pointed star” logo and dated from 1842.

During the course of my research, I’ve also discovered that Itier once served as French attache at Peking, China. Between 1843 and 1846, he visited several Asian countries and took daguerreotypes of people and places he encountered along the way.

Some of Itier’s surviving plates show the earliest portraits of Singapore, Borneo, and–surprise, surprise–Manila! He even described some of our ancestors as peaceful and meek, far from being the savages portrayed by the Westerners.

Is Jules Itier the same person who shot the Manila daguerreotypes discovered in New York City? Maybe. But one sure thing we know so far, and that is both the housings and plates are of French origin.

As for the real story behind these old pictures, we have to dig a little bit deeper to find the answers…

Faded photographs, eternal stories

The Manila daguerreotypes were donated by a civil engineer named Charles Massa to the Hispanic Society of America in 1929. His gift also included a historical handbook for those traveling to the Philippines, several photo albums, and nine ambrotypes, or the updated and cheaper version that slowly replaced daguerreotypes starting in the 1850s.

There’s no existing clue that could explain how the daguerreotypes ended up in Massa’s possession. The identity of Massa is a mystery in itself: Not much is known aside from the fact that he once owned a business related to design, was born in New York, and lived in New York City during the time of the donation.

READ: Rare Photos of Manila City Hall from 100+ Years Ago

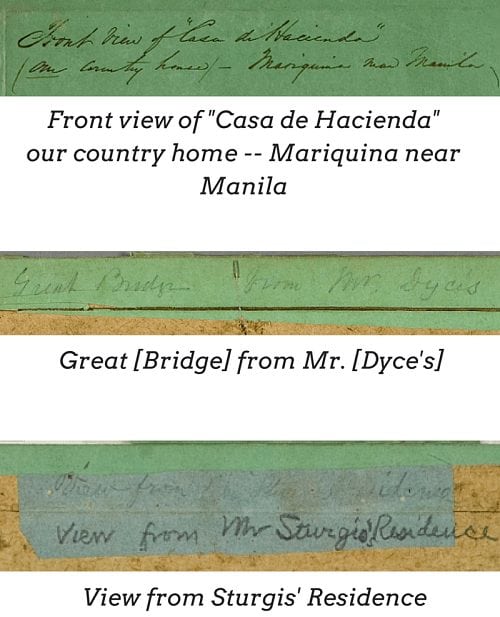

On the back of the daguerreotype housings were inscriptions made by at least five different people. They indicate the exact location where the photos were taken. Three of these inscriptions, as shown below, also give us valuable clues about the people and stories related to these faded photographs.

From these clues, we can extract three information. First, whoever took these photos were obviously fluent in English. Second, the first inscription suggests that the owner once lived in a “country home” (meaning a secondary residence) in Mariquina. Lastly, the mention of the names “Mr. Sturgis” and “Mr. Dyce’s” hints that the photographer was closely related to these people.

Noemi Espinosa, the assistant curator at the Hispanic Society of America, went on a search to find out more about these names. She discovered that H.P. Sturgis, whose name also appears on the box containing the ambrotypes, was, in fact, Henry Parkman Sturgis who co-founded Russell & Sturgis Company of Manila in 1828.

Also Read: 0 Rare Yearbook Photos of Influential Filipino Personalities

The Sturgises were among the first American families who settled in the Philippines long before the Philippine-American War. Their company, considered as the “greatest hemp and sugar-cane company” in the Philippines, remained active until 1875. “Mr. Dyce’s,” meanwhile, could be the Englishman who led a trader insurance company established in Manila in 1850.

Let’s now have a closer look at the 18 stunning Manila daguerreotypes organized into four groups: Manila district, Manila proper, Marikina, and provinces along the Laguna Lake. If you prefer a real-life encounter, you might want to visit the Hispanic Society of America in New York City.

Take note that this is for educational purposes only. Use of these photos for other reasons requires permission from Ms. Caroline Barcella, Hispanic Society of America, and the George Eastman House.

I. Manila district (circa 1840s-1850s)

II. Manila proper (circa 1840s-1850s)

III. Mariquina (circa 1840s-1850s)

IV. The Laguna (circa 1840s-1850s)

© George Eastman House/Hispanic Society of America

Philippine photography: A brief history

Daguerreotypes were first introduced to the world in 1839. Surprisingly, it only took a few years before it reached the Philippines, making it one of only two countries in Asia (the other one is India) who first used this early photographic process in the region.

The book Informe sobre el estado de las islas Filipinas en 1842 is the first to ever mention photography in the Philippines. It was written in 1843 by the Spanish diplomat, poet, and adventurer Sinibaldo de Mas who, according to a book by Antoni Homs i Guzmán, also introduced the use of daguerreotypes in the country in 1841.

Working as a diplomat of the Spanish government, Sinibaldo didn’t get enough financial support from his bosses. In order to survive, he traveled around the Philippines armed with his camera. He reportedly took photos of the natives or places he visited and later sold the pictures.

How and where he got his daguerreotype camera remain a mystery, but there are two possible answers: First, he probably bought it in India in 1840, the same year the camera was first sold commercially in that country. Historical records show that Sinibaldo was in Bengala, India in 1839 and stayed there before going to the Philippines a year later. It’s also possible that a Spaniard who was connected to Sinibaldo first bought the camera in Spain and had it shipped to Manila.

Also Read: 7 Rare Photos From Philippine History You’ve Never Seen Before

Whatever the reason, we’ll probably never confirm it as no daguerreotypes by Sinibaldo have survived, perhaps because of the country’s tropical climate.

Before the discovery in New York, we’d been told that the oldest existing photos from the Philippines were taken in the 1860s. The daguerreotypes show several Tinguian natives from the Abra province and were part of a collection by an unnamed French engineer.

The Tinguian photos were later ‘dethroned’ by two older photos from the 1840s. One of them is a view of Intramuros, Manila while the other is a portrait of the photographer W. W. Wood. However, no one can pinpoint exactly how old these photos are, with some believing that Wood’s portrait was probably shot in another country and brought here when he decided to open a studio in Manila.

The use of photography in the Philippines became widespread starting in the 1860s. The growth of the industry was more evident by the time the Suez Canal officially opened in 1869, enabling cameras and other photographic products to be easily transported from Europe to the Philippines.

Among the first establishments to sell these products were Zobel’s pharmaceutical on Calle Real 13 and the pharmacy owned by Pablo Sartorius, Rafael Fernández, and Jorge de Ludewig.

Also Read: 10 Lesser-Known Photos from Martial Law Years That Will Blow You Away

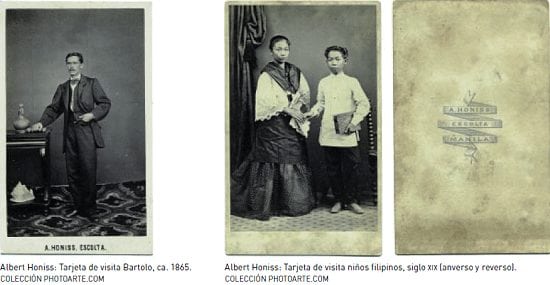

The 1860s also saw the establishment of the first photo studios in the Philippines, the oldest of which was owned by the British photographer Albert Honiss. This Escolta-based studio, founded in 1865 and remained active until 1874, was commissioned to take pictures of the Russell & Sturgis Company as well as produce the beautifully-made photo album Vistas de Manila (Views of Manila).

Honiss was also credited for making excellent visiting cards from the 1860s, two of which show a Spaniard identified as “Bartolo” and two young Filipino schoolchildren.

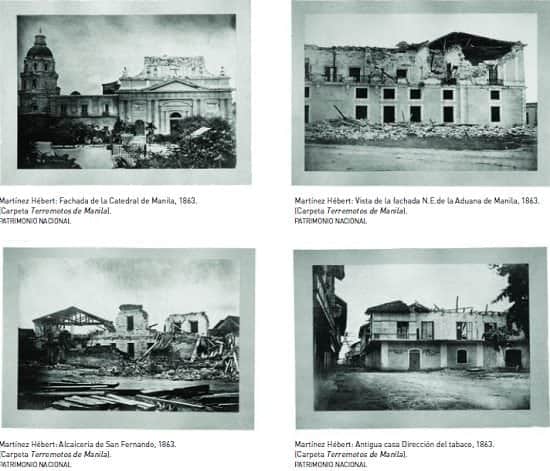

Scenes from the tragic aftermath of the 1863 earthquake have also been preserved through photographs. The pictures, taken by the photographer of the Spanish Royal Household named Martínez Hébert, show the serious impact that the disaster had towards various religious and government buildings

The casualties included the Manila Cathedral, the San Fernando Market, and the residence of the Danish Consul, among others. These rare images are now kept in the Archive of the Royal Palace in Madrid.

A lot of things have changed in terms of how Filipinos use and perceive photography. But one thing remains constant, and that is our curiosity. The fact that you’re reading this article only shows how powerful photographs are in grabbing someone’s attention.

We use pictures to learn, to evoke emotions, to deliver a message, and to bring out change. Photos can also be the window to our past, a way for us to look back on where we came from without relying on texts and boring historical facts alone.

History comes alive when we have pictures to pique our curiosity. So the next time you see a very old photograph, look deeper and you might see an amazing story unfold.

References

(1991). DLSU Dialogue, 24(2), 23.

Barcella, C. (2009). Conservation Project of the Manila Daguerreotypes. George Eastman House-Notes on Photographs. Retrieved 25 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/MDjiFZ

Griggs, B. (2014). This may be the oldest surviving photo of a human. CNN. Retrieved 25 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/gBCqoo

Guardiola, J. (2006). El Imaginario Colonial: Fotografia en Filipinas durante el Periodo Espanol 1860-1898. Spanish Society for Cultural Action Abroad.

Hannavy, J. (2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography (p. 1314). Routledge.

Lee, F. (2011). An Outpost for Old Spain in the Heights. The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/YpYejJ

The First Photograph. Harry Ransom Center – The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 25 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/EhuVV7

Written by FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net