8 Amazing Facts About Philippine History You Never Learned in School

There’s more to learn in Philippine history beyond Jose Rizal and Andres Bonifacio. Sadly, history is so vast a subject that it’s nearly impossible to know everything during our brief high school stay.

Here are eight astonishing trivia that your Philippine history teachers might have missed.

Table of Contents

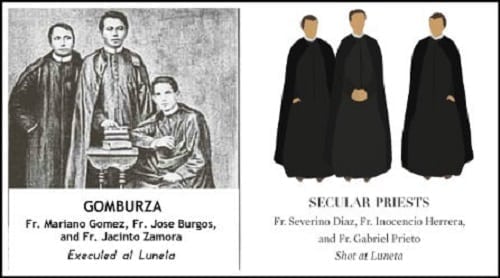

8. There Were Three Other Martyr Priests Aside From “Gomburza”

The words “martyr priest” usually conjure images of the “Gomburza,” an amalgam of the names of three Filipino priests who were executed for their alleged involvement in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny.

But several years after their deaths, another three martyr priests would again shed their blood in Bagumbayan. Their names are much more obscure, though, mainly because they were part of a group of Bicolano martyrs collectively known as Los Quince Martires.

After discovering Katipunan in September 1896, the Spanish government immediately ordered mass arrests of those connected to the secret organization. The wrath of the Spaniards eventually reached Bicol, and arrests were made between September and October 1896.

A total of 15 men were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to death. Of these 15, three were secular priests from Nueva Caceres (now Naga City): Fr. Severino Diaz, Fr. Inocencio Herrera, and Fr. Gabriel Prieto.

Fr. Severino Diaz y Lanuza was the first secular priest to head the Cathedral of Nueva Caceres. Fr. Innocencio Herrera, on the other hand, was a native of Pateros in Rizal. He moved to Bicol and became a secular priest and choirmaster at the Cathedral under Diaz. Both priests were arrested on September 19, 1896, and suffered grave torture thereafter.

The third priest, Fr. Gabriel Prieto y Antonio, was implicated when his brother, Tomas, was forced to give up names under severe torture. He was arrested at the parish house in Malinao, Albay, on September 22, 1896, under the orders of then Albay Civil Governor Angel Bascaran. Like the other two priests, he also suffered verbal and physical torture after his arrest.

Bound in ropes and chains, the three priests and other prisoners were transferred to Manila aboard the steamships Ysarog and Montañes. They were temporarily imprisoned in the convent of San Agustin in Intramuros before being transferred to the Bilibid Prison, where they would stay until their execution by firing squad on January 4, 1897.

7. The First American Hero of World War II Was Killed in Combat in the Philippines

A graduate of West Point, 25-year-old Capt. Colin P. Kelly Jr. became the first American hero of World War II when he bombed a Japanese cruiser three days after the attacks in Pearl Harbor.

On December 10, 1941, Kelly and his crew were ordered to fly out of Clark Air Field and attack targets on Formosa (now Taiwan). He was forced to take off the B-17 with only three 600-pound bombs, and the plane partly fueled.

On the way to Formosa, they saw a huge Japanese landing party with accompanying destroyers. Kelly ordered the attack on the Japanese fleet despite receiving no clear permission from the base to engage the enemy.

The crew dropped the bombs from 20,000 feet. One bomb directly hit the target while the other two impacted the flank. With no bombs left, Kelly maneuvered the plane to return to Clark Air Field.

Unfortunately, the plane was almost back to its home airfield when two enemy planes attacked it. Kelly ordered his crew of six to bail out while he remained in the plane until it exploded.

After his death, it was discovered that Kelly’s bomber had hit a light Japanese cruiser named Ashiraga, not the battleship Haruna as earlier reports had suggested. For this reason, Gen. Douglas MacArthur lowered the recommendation to the Distinguished Service Cross.

To honor his heroism, a post office and a highway in his hometown in Florida were named after him.

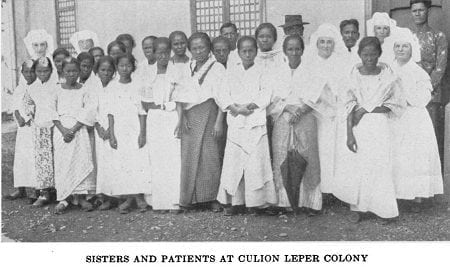

6. Philippines’ Leper Colony Had Its Own “Leper Money”

Leprosy is a communicable bacterial disease characterized by skin lesions and numbness. In 1633, it was said that a Japanese Emperor sent a ship loaded with lepers to the Spanish missionaries based in the Philippines. He also instructed the ship’s captain to drown the lepers in case no one would receive them.

Fortunately, the missionaries kindly welcomed the patients with open arms and even established the San Lazaro Hospital to care for them. At that time, people had very little knowledge about the disease, so it didn’t take long before leprosy started to afflict the Filipino populace.

In 1906, the Director of Health for the Philippines, Dr. Heiser, opened a leper colony in Culion, an island located north of Palawan. Lest they might continue spreading the disease, a unique monetary system separate from the rest of the country was established. These leper coins were only allowed within the colony, and those who would leave the place had to convert the leper money into “government money.”

Leper money was strictly regulated, and those who violated the law would pay a fine, stay in prison for up to 1 month, or both.

The first few issues of the leper coins were made from aluminum, but it was later replaced by copper nickel as those made from aluminum were easily damaged by chemicals used to disinfect the coins.

5. Before Martial Law, There Was the Colgante Bridge Tragedy

On September 16, 1972, a few days before the declaration of martial law, the Colgante bridge in Naga City collapsed, killing 114 Roman Catholic pilgrims celebrating the feast of their patroness, Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia.

Most of the victims were either drowned or crushed to death on boats beneath. The tragic incident happened when 1,000 faithful rushed to the 15-year-old Bailey bridge to watch with excitement the fluvial procession that would bring the image of their patroness from Naga Metropolitan Cathedral to her shrine.

Several broadcast journalists covering the event also perished in the tragedy. One of them is Miss Mila Obia, who was announcing the approach of the religious image using her local dialect when the bridge suddenly collapsed.

Incidentally, this was the second time the bridge claimed many lives during a fluvial procession. In 1948, the old Colgante bridge–which was only a suspension type back then–fell into the river and left 30 people dead.

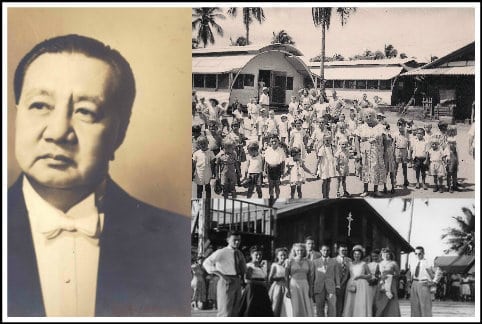

4. President Elpidio Quirino Helped Save the Lives of Almost 6,000 “White Russians”

If President Quezon was the savior of the Holocaust Jews, President Quirino should be the unsung hero of “White Russians.”

In 1948, China was on the brink of a total invasion by the Communists led by Mao-Tse-Tung. For this reason, Russian emigrants living in Peking, Hankow, Tiensin, and other nearby cities in northern China were forced to evacuate to Shanghai. However, they were aware that the Communist army would eventually take over the rest of China, so they had to move somewhere else or end up dying in Russian labor camps.

This is when the International Refugee Organization (IRO) came to the rescue. They knew the danger that might ensue, so they asked for help from other countries to provide temporary shelter for the “White Russians.”

These “White Russians” were named after the color of the tsarist court and the Russian soldiers’ uniforms. If you can recall your world history, the “White Russians” were opposed to the Communist regime (i.e., the “Red Russians”) who went against the Tsar during the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. The conflict resulted in a civil war, forcing the White Russians to transfer to other countries, including China.

Also Read: The Forgotten Story of Japanese Christians – Philippines’ First Refugees

Going back to IRO, no country had responded to their plea for fear of China. They were about to lose hope when the Philippines under President Elpidio Quirino agreed to convert the tiny island of Tubahao in Eastern Samar into a Russian refugee camp. In 1949, about 5,000 to 6,000 White Russians finally arrived and settled in Tubahao for about 27 months.

The Russian Refugee Camp was divided into 14 districts, and the White Russians who stayed there had their hospital, electricity, churches, and a cemetery. After more than two years on the island, most of the refugees were eventually admitted to other countries like France, Australia, and the United States.

To honor Quirino’s act, a Russian sculptor made a bronze artwork featuring the late Philippine president being blessed by St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco. It was unveiled in 2011 in the Philippine Trade Training Center lobby in Pasay City.

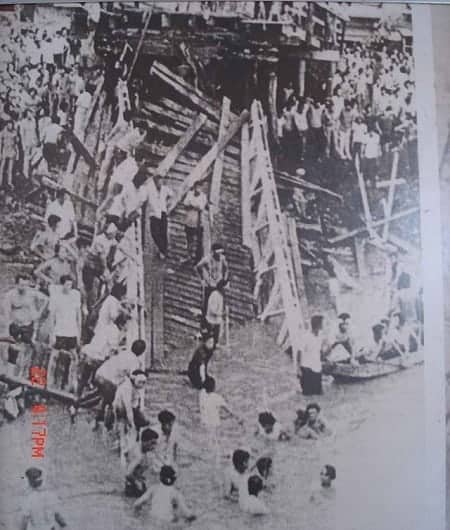

3. In 1942, Almost 16 Million Silver Coins Were Dumped Near Corregidor. Some of It Remains Unretrieved

After the Fall of Manila in 1942, Filipino and American officials were thinking of ways to keep the Philippine National Treasury out of the enemy’s hands. At that time, the treasury was brimming with 70 million pesos in paper bills, 269 pieces of gold bars, and 16,422,000 pesos in silver coins.

They were running out of time, so they had to move fast. After recording the serial numbers, 20 million in 500-peso bills were burned from January 19 to 20, 1942. When the submarine U.S.S. Trout arrived in Corregidor on February 3, workers loaded it with 2 million dollars in gold bars and $360,000 in silver, eventually shipped to San Francisco.

With no more time left, high court government officials dumped the remaining 15,792,000 pesos in silver coins to Caballo Bay, a deep and rough location just off Corregidor.

For some reason, the Japanese learned about the sunken treasure right after the fall of Corregidor. Soon, they sought the help of Filipino divers–some of whom died due to drowning–to salvage the boxes of silver coins. Ultimately, they only recovered $54,000 or 100,000 pesos.

But the Japanese wouldn’t settle for less, so they handpicked more experienced divers from a group of American prisoners. From June 20 to September 28, 1942, the American divers retrieved 150,000 pesos. Of course, it was hazardous work, and they thought of only one way to retaliate: outsmarting the Japanese.

Indeed, they could steal 30,000 to 60,000 pesos without the Japanese knowing. Their Filipino friends found Chinese money changers in Manila to exchange Japanese paper currency for Philippine silver coins. Some coins were also passed off to other prisoners of war who would later use the money to bribe Japanese soldiers.

Eventually, the recovery program was canceled, much to the joy of American prisoners. In 1945, the U.S. Navy salvaged 5,380,000 pesos which they turned over to the Philippine government.

Although 75% of the sunken treasure was already recovered, no one knows precisely how much of it remains at the bottom or if it can still be retrieved in the first place.

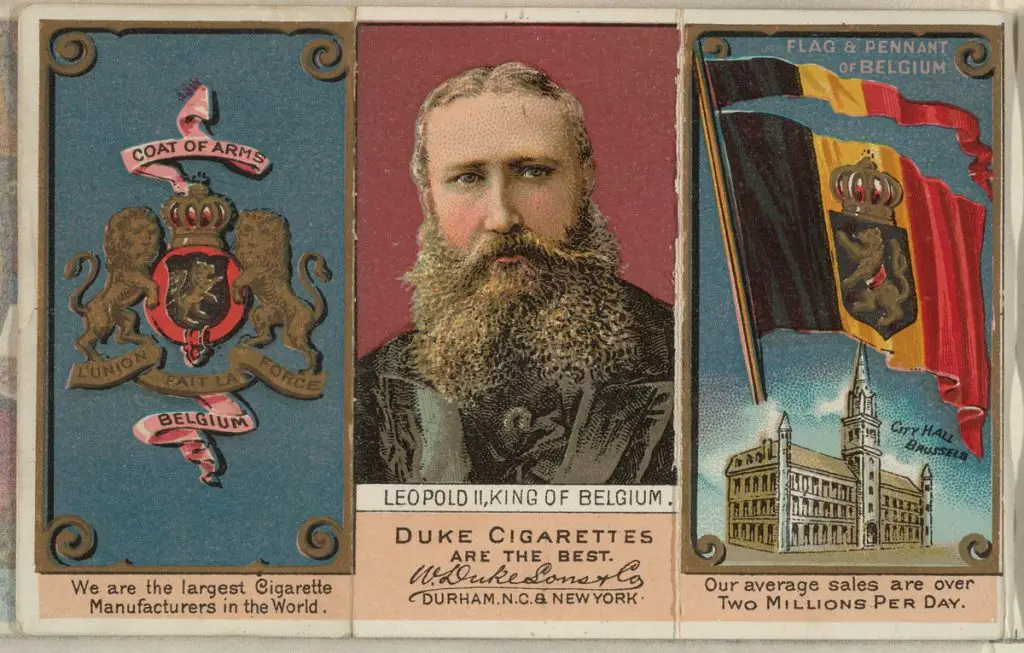

2. A Belgian King Almost Bought the Philippines From Spain

King Leopold II of Belgium was passionate about geography and everything that had something to do with maps. He also loved to travel, and during one of his trips, he realized that he could turn Belgium into one of the world’s wealthiest countries.

To make this possible, he first needed a colony. His focus then shifted to Asia, specifically the islands considered to be the gateway to other nearby countries: the Philippines.

According to historian Ambeth Ocampo, most details of King Leopold’s quest to make the Philippines a Belgian colony can be found in the 1962 book A La Recherde d’un Etat Independent: Leopold II et les Philippines 1869-1875.

In 1866, a year after he acceded to the throne, King Leopold II asked his ambassador in Madrid to negotiate with the Queen of Spain about possibly ceding the Philippines to Belgium.

But here’s the catch: It was common knowledge then that Leopold’s government was against his imperialistic plans. They believed colonization “entails naval vessels and an army to protect interests halfway across the world,” and Belgium was not yet ready to take that risk.

As expected, his first attempt failed. And so was the second when he even attempted to get personal loans from English banks, which ended in rejection.

He also devised a scheme to turn the Philippines into an independent country and later a colony under the Belgian monarch. Unfortunately, this, too, failed miserably.

Ultimately, his dream of having a colony finally came true when he proclaimed his sovereignty over Congo, an African country.

1. A Filipino Dwarf Became a Famous Figure in 19th-Century Britain

Don Santiago de los Santos, a Filipino dwarf, became part of a traveling show in England between the late 1820s and the early 1830s. He was a local celebrity in that part of the world.

So, how did he end up in England?

Popular journals from the late Georgian and Victorian eras had documented his story, although they might have exaggerated some of the details to sell more copies.

The existing documents suggest that Don Santiago de los Santos was born in 1786 to poor parents. The 1836 edition of the Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (Volume 28) went on to say that he is

“….a native of the Spanish settlement of Manila; in one of the forests of which, it seems, he was exposed to death in his infancy, on account of his diminutive size. He, was, however, miraculously saved by the Viceroy, who, happening to be hunting in that quarter, humanely ordered him to be taken care of and nursed with the same tenderness as his own children, with whom the little creature was brought up and educated, until he attained the age of manhood.”

Sadly, the Viceroy died when he was 20 years old. His foster brothers and sisters moved to Spain shortly thereafter, while Santiago decided to stay because of his “attachment to the land of his birth.”

That decision proved to be futile. Neglected by his own family, he “found his way to Madras, and was brought to England by the captain of a trading vessel.”

The journal also reveals some of Don Santiago’s unique characteristics. He was described as “stoutly built” with “slight copper” complexion. He also liked “glittering attire, jewellery, and silver plate.” And just like Jose Rizal, Don Santiago was also multilingual: He could speak his native tongue and Indian patois, Portuguese, and English.

He later married Anne Hopkins, a 29-year-old dwarf from Birmingham slightly taller than him (she was thirty-eight inches tall while Don Santiago was only twenty-five inches high). However, they faced a minor hurdle before they could tie the knot. According to the 1848 edition of The London Lancet,

“..a protestant clergyman hesitated to marry them, on the presumption that it was contrary to the canon law, as being the means of propagating a race of dwarfs; but in this he was overruled by the high bailiff of Birmingham, and some legal opinions.”

They were finally married on July 6, 1834, at two separate churches in Birmingham (Santiago was a Roman Catholic while his wife was a Protestant).

Anne Hopkins eventually gave birth to a child, but it was not a happy ending:

“…the infant, though it came to the world alive, did not survive its birth above an hour. Its length is thirteen inches and a half; its weight is one pound four ounces and a half, (avoirdupois;) it is in every respect well formed; and the likeness of its face to that of the father is very striking.”

References

Barrameda, J. (2012). The Bicol Martyrs of 1896 revisited. Bicol Mail. Retrieved 2 October 2015

Cheng, J. (1960). Silver Coins Buried Under The Sea. The Quan, p. 3.

Davies, H. (1848). On Account Of Two Labours Of A Dwarf, With Some Observations On The Operation Of Craniotomy, And On The Induction Of Premature Labour. The London Lancet: A Journal Of British And Foreign Medical And Chemical Science, Criticism, Literature And News, 8, 31-32.

Garvey, J. (2007). San Francisco in World War II (p. 26). Arcadia Publishing.

Hubbell, J. The Great Manila Bay Silver Operation. Corregidor.org. Retrieved 2 October 2015

Labro, V. (2011). ‘White Russians’ return to refugee island. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 2 October 2015

Limbird, J. (1836). J. Limbird. The Mirror Of Literature, Amusement, And Instruction, 28, 295.

Lodi News Sentinel,. (1972). Bridge Collapse Kills Catholics, p. 13.

The Milwaukee Journal,. (1941). Heroes of the Philippines Honored By MacArthur, p. 3.

Wheeler, M. (1913). The Culion Leper Colony. The American Journal Of Nursing, 13, 663-665.

Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito E. Batongbakal Jr. is the founder, editor, and chief content strategist of FilipiKnow, a leading online portal for free educational, Filipino-centric content. His curiosity and passion for learning have helped millions of Filipinos around the world get access to free insightful and practical information at the touch of their fingertips. With him at the helm, FilipiKnow has won numerous awards including the Top 10 Emerging Influential Blogs 2013, the 2015 Globe Tatt Awards, and the 2015 Philippine Bloggys Awards.

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net