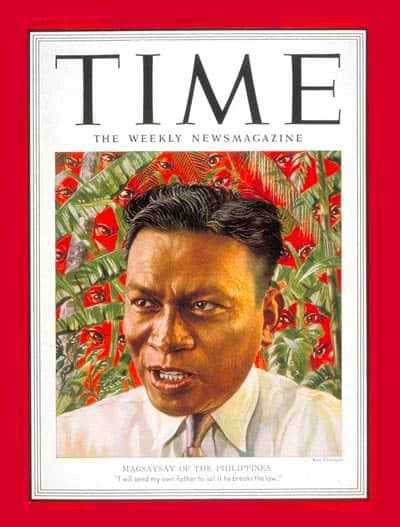

Ramon Magsaysay: 6 Reasons Why He’s The Best President Ever

Honest and efficient presidents are like white lions–they are a breed of politicians so rare we sometimes think they don’t exist anymore.

And then came Ramon Magsaysay, the humble automobile mechanic-turned-president who became known as the “Champion of the Masses.” We remember him as the one who blazed a trail through his “servant leadership” in the 1950s–half a century before President Noynoy Aquino uttered the words “Kayo ang BOSS ko!” in his inauguration address.

Also Read: Unsolved Mystery – The Magsaysay Plane Crash

Magsaysay was not a perfect president; his administration faced several issues and controversies. But his greatness overshadowed the flaws of his administration, and had he not died in that plane crash, he would have achieved more than all his successors.

In author Jose Veloso Abueva’s words, despite its brevity, Magsaysay’s governance remains “the yardstick by which Filipino presidents should be judged.”

So, is Magsaysay the best president our country ever had? Read this article, and you be the judge.

Table of Contents

1. His Brilliant Counterinsurgency Efforts Were Unprecedented

In the early 1950s, the insurgency launched by a group of peasant farmers called Hukbalahap (Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon or People’s Anti-Japanese Army) was at its peak. Both the previous and incumbent presidents struggled to stop the rebellion: Roxas banned the organization in 1948, while his successor, Quirino, was stained with corruption and cronyism, infuriating the Huks even more.

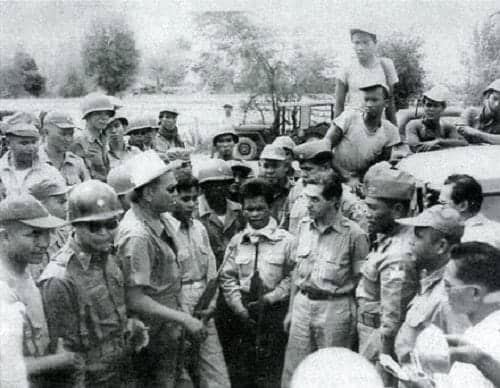

Desperate to stop the Hukbalahap threats from worsening, Quirino made a strategic move: He appointed Ramon Magsaysay–a celebrated WWII guerrilla leader–as the new Secretary of National Defense. As a new appointee, Magsaysay did what his predecessor failed to do: He identified the root cause of the problem and started from there.

Also Read: 10 Unforgettable Pinoy Politicians We Wish Were Still Alive

With the help of Lieutenant Colonel Edward G. Lansdale, an Air Force intelligence officer who served as his advisor, Magsaysay toured the whole country and saw firsthand the driving force behind the insurgency. At that point, he realized that most of the Huks were not Communists; they were simple peasants who thought that rebellion was the only answer to their suffering.

In the words of historian Teodoro Agoncillo, the Hukbalahap was the “culmination of centuries of peasant degradation, loss of self-respect, and abject poverty.”

Of course, for Magsaysay to execute his plans to end the rebellion, he needed the help of the Armed Forces. But here’s the catch: The country’s military arm was also suffering from several issues, the most serious of which were poor leadership, corruption, and a patronage system.

In other words, ending the insurgency wouldn’t be possible without first addressing the serious problems plaguing the Armed Forces. It was a challenging task, but this is when Ramon Magsaysay showcased his exemplary leadership skills and political prowess.

Magsaysay completely transformed the AFP. He fired the AFP Chief of Staff, the Chief of Constabulary, and other officers implicated in graft and corruption. He also changed how the AFP fought the insurgents, emphasizing that “the Huks are fighting an unorthodox war,” so they should also fight them “in unorthodox ways.”

This warfighting innovation, also known as “Find Em, Fight Em, Fool Em,” combined intelligence, combat operations, and psychological warfare.

Eventually, the Huk rebels were tracked down, and their members surrendered one after another, culminating in Luis Taruc’s arrest on May 17, 1954. All of these were achieved through the newly revamped AFP and Magsaysay’s social reforms, namely the legal assistance program for the peasants and the Economic Development Corps (EDCOR), a rehabilitation program that gave surrendered Huks an opportunity to have their own houses and land.

Magsaysay’s military and social reforms were so effective that the Communist Party leader Jesus Lava himself admitted that many Huk soldiers left the insurgency group “because repression was ending.”

2. He Gave Land to the Landless

When Magsaysay ran for president, the barrio-to-barrio campaigns only opened his eyes even more to the issues of the rural folk neglected by previous presidents.

He realized that the Philippine government shouldn’t be a government of the elites but an entity fully dedicated to the welfare of all its people–especially the peasant farmers long considered to be the “backbone of the nation.”

Magsaysay believed that insurgency would continue to exist as long as the government stayed deaf to the calls of the rural folk. “To be really secure,” he once said, “a country must assure for its citizens the social and economic conditions that would enable them to live in decency, free from ignorance, disease, and want.”

Also Read: A Touching Story of How Filipinos Saved A Million Lives At The Most Unexpected Place

Magsaysay became the voice of the voiceless, and his impressive rural development programs only proved that he was sincere in uplifting the lives of the oppressed.

To turn his vision into a reality, Magsaysay implemented several projects–all for the benefit of the rural poor.

He improved the land tenure system through the Agricultural Tenancy Act in 1954, which gave tenants the “freedom to choose the system of tenancy under which they would want to work,” and the Land Reform Act of 1955, passed to enhance landlord-tenant relations.

Also Read: 10 Famous Filipinos Who Almost Became President

Public lands were also distributed to qualified settlers: 28,000 land patents covering 241,000 hectares were issued during the first year of the Magsaysay administration alone. By 1955, an impressive 23,578 agricultural lots were distributed to landless applicants. In the same year, 8,800 families were also resettled by the National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Administration (NARRA) in 22 settlement projects.

Magsaysay also initiated intensive community development through the Presidential Assistant for Community Development (PACD). The said agency helped build roads and other facilities for the rural folk and improved the medical and educational services in the barrios.

3. Ramon Magsaysay Created a Government of the People, by the People, for the People

President Ramon Magsaysay was genuinely pro-Filipino. For instance, he wore the traditional barong Tagalog during his inauguration. He also used the Ilokano wine called basi to exchange toasts with foreign diplomats and took every chance to promote local products.

For the Filipino people, however, Magsaysay’s most memorable achievement was his effort to earn back people’s trust in the government. Known as the “The Champion of the Common Man,” Magsaysay would listen to the problems of the ordinary “tao” at least two to three times a week. He established the Presidential Complaints and Action Committee (PCAC) to make sure that the complaints of the masses were taken care of.

Filipinos gained the courage to condemn corrupt public officials without fear of repression for the first time in many years. PCAC was so successful that in 1954 alone, they already received 59,144 complaints.

Also Read: Ramon Magsaysay’s Haunting Last Photo

Wanting to prove that his government was for the people, Magsaysay also opened the doors of the Malacañang Palace to all its citizens–and he meant it literally. Soon, the masses began swarming the official residence, transforming the lawns into picnic grounds. So many people flocked to Malacañang during the Magsaysay era that some began to describe it as a “miniature Divisoria,” a combination of market and cockpit.

4. He Is a Good Role Model for the Youth

Magsaysay’s upbringing explains why he became a man of principle. Born in Iba, Zambales, to a blacksmith and a schoolteacher, the young Ramon Magsaysay was trained to respect the elders and develop humility, honesty, frugality, and a love for hard work.

It is said that when he was only six years old, Magsaysay’s father, Exequiel, lost his job in a public school after refusing to pass the school superintendent’s son in his carpentry class. For this reason, the Magsaysays were forced to move to Castillejas, where Exequiel built a small blacksmith shop to support his family.

Although a minor hurdle, this experience instilled the importance of honesty and clean living in the young Monching.

As a young man, Monching loved to play with other boys of his age. He was a bit of a prankster, but he never forgot how to respect and shower his parents with love. Exequiel bought several blocks of ice one day because he expected to receive several guests the next day. He was planning to make ice cream but was surprised that the buried ice blocks were missing.

Also Read: 11 Reasons Why Jose P. Laurel Was A Total Badass

As it turned out, Monching and his friends took the ice blocks the night before, drove out of town, and enjoyed all the ice cream they made. In her biography, Perfecta (Monching’s mother) described how furious his husband was when he discovered no ice. He immediately rushed towards the rice field, where he found Monching with the other children.

Exequiel was so mad that he was ready to spank his son. However, his heart melted when Monching showed him the ice cream and said, ‘Father, I brought the ice in the field to make the ice cream myself so that you won’t get tired making it.’ In the end, he gave more ice cream to the boys, and what was left behind was given to the guests.

5. He Refused Special Treatment

The masses loved President Magsaysay because he didn’t think highly of himself. He earned people’s trust because of his humility and sincerity in addressing the needs of ordinary citizens.

Unlike other politicians, Magsaysay refused to name towns, bridges, avenues, and plazas after him. He lived in a simple home, wore simple clothes (usually an “aloha” shirt and slacks), drove his car, and spoke a language easily understood by the masses. Indeed, the late President Ramon Magsaysay was the epitome of simplicity.

He wanted to set an example, someone that other public officials would look up to. For example, when he was still a Defense Secretary, he refused special treatment and lived within his means–a government salary of about $500 a month.

Historian Xiao Chua also shared two anecdotes about the great president. It is said that while Magsaysay was on his way to Malacañang to meet then-President Elpidio Quirino, their car suddenly stopped. Because his driver, Kosme, was clueless about fixing it, Magsaysay–who once worked as a mechanic at the Try Transportation Bus Company in Manila–didn’t think twice about fixing it himself, even while wearing a barong Tagalog.

The same driver also once violated traffic rules. When the policeman saw the plate number and the passenger in the car, he allegedly said, “My goodness! Pardon me, Mr. President. You can now proceed.”

Also Read: 10 More Haunting Last Pictures Ever Taken in Philippine History

However, Magsaysay refused to accept the “privilege” and said this instead: “Oh no, Sargeant. You said a while ago that the law is the law. And in that principle, I do believe. While I am the president, the law applies to everyone; there is equality. Please give us the necessary ticket.”

6. Ramon Magsaysay Banned Nepotism and Corruption

President Ramon Magsaysay had all the qualities an ideal politician should have: Unpretentious, selfless, and utterly uninterested in money.

While the rest of Philippine politics was plagued with nepotism and a “compadre system,” Magsaysay worked hard to break the stereotype. He wanted to set an example, so he put the needs of the Filipino people above all–even at the expense of his relatives.

He hated nepotism so much that when he learned that a community well was being dug on a property owned by a relative, he immediately sent a directive and had the well moved to the middle of the village square. On the other hand, an uncle failed to get a big government cement contract after Magsaysay personally canceled the order.

He also banned his brother, who was a lawyer, from accepting any case for anyone connected with the government or for anyone “who wants to get close to the government.”

Magsaysay also hated corruption and started to fight it as soon as he entered Philippine politics. For example, on his first day as Defense Secretary, he fired several high-ranking officials in the AFP–including the Chief of Staff and the Chief of the Constabulary–as part of his military reforms. His administration was synonymous with honesty and clean governance when he became president.

Also Read: 10 Things Filipino Politicians Must Stop Doing

Such was his effort to combat graft and corruption that public officials–from top to bottom–started to fear his presence. “Every time I sit here and look at my stamp drawer,” recalled a local postmaster, “I start to think, well, I don’t have much money and my family needs food, maybe I ought to swipe some. Then I start thinking that that damn Magsaysay might suddenly show up … just as my hand is going into the petty cash drawer, and he’d throw me in jail.”

References

Agoncillo, T. (2012). History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc., pp.474-488.

Chua, M. (2012). Ramon Magsaysay: Role Model for the Youth. [online] It’s XiaoTime!. [Accessed 9 Sep. 2014].

Francisco, R. (2013). Magsaysay and the AFP: A Historical Case Study of Military Reform and Transformation. [online] Presidential Museum and Library.[Accessed 6 Sep. 2014].

Gin, O. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1. 1st ed. ABC-CLIO, p.54.

Greenberg, L. (1986). THE HUKBALAHAP INSURRECTION, A Case Study of a Successful Anti-Insurgency Operation in the Philippines, 1946-1955. [Case study] Library of Congress, Historical Analysis Series. Washington, D.C.

Halili, C. (2004). Philippine History. 1st ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc., pp.257-260.

Magat, M. (2013). Ramon Magsaysay’s continuing relevance. [online] INQUIRER.net. [Accessed 9 Sep. 2014].

Rivett, R. (1954). Magsaysay–The Racket ‘Killer’. The Argus, [online] p.4. Available [Accessed 6 Sep. 2014].

Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito E. Batongbakal Jr. is the founder, editor, and chief content strategist of FilipiKnow, a leading online portal for free educational, Filipino-centric content. His curiosity and passion for learning have helped millions of Filipinos around the world get access to free insightful and practical information at the touch of their fingertips. With him at the helm, FilipiKnow has won numerous awards including the Top 10 Emerging Influential Blogs 2013, the 2015 Globe Tatt Awards, and the 2015 Philippine Bloggys Awards.

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net