10 Notorious Crimes of the 1960s That Shocked The Philippines

The Vizconde Massacre, the Hultman case, the Marikina killings, and the Ampatuan Mass Murder. These were just a few gruesome crime stories that hogged media headlines for months–even years–in recent memory. But there were cases just as shockingly chilling, perhaps even more so, as these sensational crimes from the 1960s.

Table of Contents

- 10. The Menace of the Face-Slashers (1965)

- 9. The Abduction of Annabelle Huggins (1963)

- 8. The 83-day Ordeal of Cosette Tanjuaquio (1964)

- 7. The Janet Clemente Conspiracy (1969)

- 6. The RCA Ax Slaughter (1963)

- 5. The Cabading Family Carnage (1961)

- 4. The Laurel-Silva Double Killing (1965)

- 3. Richard Speck and the Student Nurse Murders (1966)

- 2. The Crime Against Maggie’s Virtue (1967)

- 1. The Jigsaw Murder of Lucila Lalu (1967)

- References

10. The Menace of the Face-Slashers (1965)

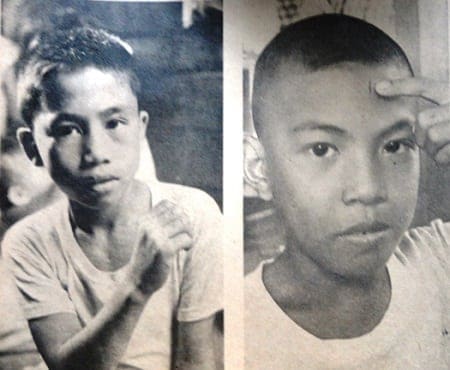

In August 1965, a mystifying rash of crimes befell young students of Manila—a series of face-slashing incidents with a knife or razor blade was perpetrated on grade schoolers and colegialas.

Tondo had the most cases, and in all instances, the modus was the same—the slasher appears from nowhere, attacks the victim, and then disappears. Capt. Felicisimo Lazaro of the Tondo precinct smiled off the case as another “teen fad” inspired, he said, by a local movie about a disguise artist, “Pitong Mukha ni Dr. Ivan.” But with over 600 cases reported, the incidents could not be dismissed as a mere gimmick.

Also Read: Top 10 Unsolved Mysteries in the Philippines

Rumors spread like wildfire about the culprits; some believed they were drug addicts, others claimed they were extortionists linked to the Karate and Bahala Na gangs—those who failed to comply were branded by a blade.

The strangest angle was that the face-slashing was a Communist plot after two posters with the Nazi swastika were found at the San Francisco del Monte Elementary School. The posters threw students into panic, caused anxiety among parents, and forced police chiefs to field 180 policemen to patrol schools.

Only two slashers in Parañaque were apprehended by the NBI, but since nothing was said beyond the admission of guilt, their motive remained a mystery to this day. By year’s end, the scar scare ceased.

9. The Abduction of Annabelle Huggins (1963)

A classic tale of “he said she said,” the case of Fil-Am actress Annabelle Huggins remains one of the top newsmakers in 1963, noted for its chaotic courtroom drama and over-the-top media reportage.

On October 23, 1962, 19-year-old Huggins reported that she was taken against her will to Hagonoy, Bulacan, and defiled of her honor by Ruben Ablaza, a portly taxi driver, who plotted the abduction with two others, Lauro Ocampo and Jose “Totoy Pulis” Leoncio. The incident was repeated on March 22, 1963, and this time, Huggins was reportedly kidnapped from Makati and taken first to Caloocan and then to Bulacan, a more serious offense.

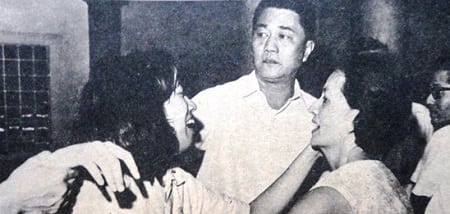

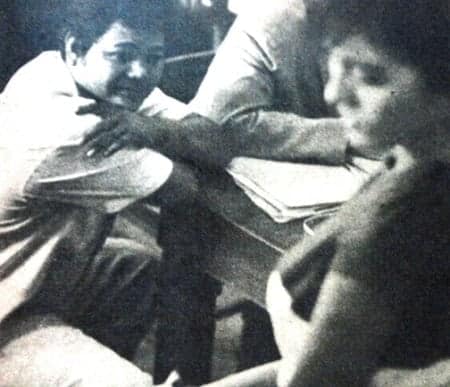

Accuser and Accused: Caught by the camera as he gazes at Annabelle Huggins is Ruben Ablaza, accused by the 20-year-old American mestiza of abduction with rape. Photographed by Dominador Suba. Courtesy of Alex R. Castro Photo Archives.

When Ablaza was apprehended and tried in court, he contended that the two were in love, that she freely went with him, and that what he did “was the vogue of the time.” The most awaited part of the trial was when the principal witness, Huggins, testified before Fiscal Pascual Kliatchko and a curious courtroom crowd.

Huggins cried hysterically for 6 hours as she recounted details of her alleged rape, testing her endurance and willpower. To add further drama, her American father, Roy Huggins—whom she had not seen for 17 years—suddenly showed up for a brief but tearful reunion.

Ablaza was found guilty of kidnapping with rape and was meted a life sentence. Ultimately, he professed his love for Huggins and his desire to marry her. Ablaza died shortly after being released from prison.

Huggins, on the other hand, went on to pursue her movie career, starring in a 1963 movie based on her harrowing experience, “God Knows”(Batid ng Diyos), and appearing in a U.S.-made war movie with Jack Nicholson in 1964.

8. The 83-day Ordeal of Cosette Tanjuaquio (1964)

For about 3 suspenseful months, the nation was riveted to the news of the kidnapping of 15-year-old Cosette Tanjuaquio. The Maryknoll coed was staying in his uncle’s Loyola Heights home when, on November 16, 1964, she was snatched by four men and just disappeared.

A PHP 50,000 reward was put up by her distraught parents, Mr. & Mrs. Calixto Tanjuaquio. Back in Cosette’s school, 500 Maryknoll students prayed religiously every day for her safe return.

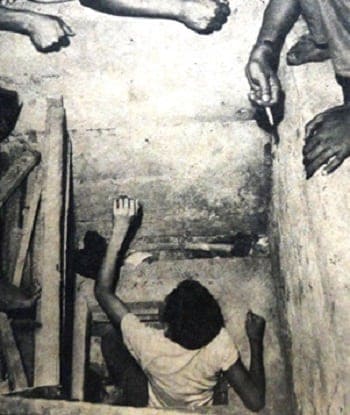

The head of the Criminal Investigation Service (CIS) himself, Col. Benjamin Tolentino, handled the Cosette case, which had a break only on January 25 when a counterfeit ring was uncovered. A syndicate member accidentally blurted out details of a “kidnapped girl.” This led to the dramatic rescue of Cosette, who was found in a World War II air raid shelter next to a pig pen, on February 7, 1965.

The dank, dirty pit, only 4 feet high, was accessible through a narrow 2 ft. x 2 ft. crevice. It was, ironically, just 4 kilometers away from the Tanjuaquio’s Guagua home.

In 1966, the kidnappers were tried, proven guilty, and sentenced by Judge Placido Ramos. Orador Pingol and Nomer Jingco, the masterminds, were sentenced to death, while followers Armando Morales and Angel David were given life sentences.

The judge recommended that the president commute the death penalty to reclusion perpetua because Pingol and Jingco never took advantage of the victim’s weakness in all the time Cosette was held captive, hence they still had the “spark of divinity” that bodes well for their rehabilitation.

7. The Janet Clemente Conspiracy (1969)

A multiple murder case allegedly under the direction of a woman was the top crime news in 1969. Club hostess Janet Hernandez Clemente conspired with Alfredo Edwards and Mario Canial in the cold-blooded murder of Benjamin Galang, Irineo Narvasca, and Zosimo Felarca in Sampaloc.

All three victims were friends of Florencio San Miguel, a common-law husband of Clarita Hernandez, Janet’s sister. For having junked Clarita, San Miguel claimed that Clemente had threatened to kill him, his relatives, and friends. The situation was exacerbated when San Miguel had a violent altercation with a Clemente relative, Ramon Hernandez.

Recommended Article: 8 Crazy Pinoy Conspiracy Theories

Things came to a head when Clemente made good her threats. On the evening of April 29, she and her cohorts stopped their white Toyota on Elias St. and started mowing San Miguel’s friends one by one with their .45 caliber pistol and carbine, with Clemente providing identifications.

The three suspects were caught, tried, and sentenced by Judge Manuel Pamaran of the Manila Criminal Circuit Court, imposing the capital punishment of death. In August 1972, their case was reviewed, and the Supreme Court reversed the decision, ruling out that the killing was not pre-meditated but a chance encounter, hence, no conspiracy.

Both Mario Canial and Alfredo Edwards were found guilty of homicide, but only Canial served time in prison, Edwards having died while waiting for the appeal. Janet Clemente was acquitted and walked away free.

6. The RCA Ax Slaughter (1963)

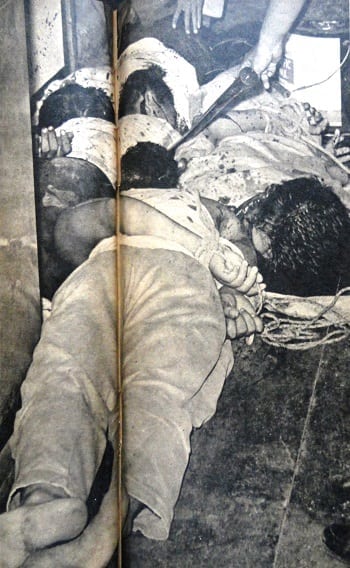

On the early dawn of August 26, 1963, Manila woke up to the horrible news wrought by a “bestial, ax-wielding gang” that left dead five security guards of the RCA Bldg, on Canonigo St., Paco, Manila.

Butchered with a 15-pound fireman’s ax were Ricardo de la Cruz, Roberto Gonzalez, Francisco Timbol, Francisco Zablan, and Alfredo Adaza, who died en route to the hospital. Two others narrowly cheated death—Turiano de Guzman hid in a guard’s room when he heard the dying moans of his companions, and carpenter Pablo Lopez walked into the gang’s lookout and was forced to join the hogtied guards. When the ax wielder started his grisly work, Lopez buried his head under the bodies of the dead and feigned death.

The gang blew off 2 RCA safes and took off with over PHP 335,000—a huge amount at that time. From the statements of the survivors, the investigators pieced the story of the heinous massacre, which turned out to be an inside job involving RCA employees: Leonardo Bernardo (driver), Mariano San Diego (guard), Mariano Domingo (guard supervisor), and Apolonio Adriano (guard, tagged as the ax-man).

The group had come in a jeep and overpowered the guards by grabbing their high-powered Thompsons. The accused were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death on March 19, 1966, by CFI Judge Placido Ramos. They were also ordered to pay PHP 218,000 indemnity to RCA, representing the unrecovered money they stole.

5. The Cabading Family Carnage (1961)

A possessive, selfish father with a violent streak triggered the senseless deaths of family members—including the perpetrator himself–in this high-profile case that left a nation shocked in disbelief in 1961.

Police detective Pablo Cabading had always been a domineering figure in his Makati household that included his wife, Anunsacion, and only daughter Lydia Cabading, a 23-year-old medical doctor. When Lydia announced her plan to settle down with 34-year-old Dr. Leonardo Quitangon, her father gave his reluctant permission—on the condition that the couple would stay in the Cabadings’ Zapote home.

That arrangement turned out to be a hellish experience for the newlyweds. Pablo controlled their every activity, often insinuating himself in the couple’s private dates, imposing curfews, and ordering his daughter to sleep in his mother’s room. His anger knew no bounds when Leonardo and Lydia expressed their wish to live independently.

To escape their father’s wrath, the two fled to Cavite. Pablo turned his wrath on his Quitangon in-laws, harassing them with a gun and a demand to return his daughter. Eventually, he succeeded in convincing Lydia and Leonardo to return to Zapote after telling them that Anunsacion had fallen ill—when in fact, she was just feigning sickness.

On January 18, 1961, Pablo invited Leonardo’s brother, lawyer Nonilo Quitangon, to his house “to discuss something important.” Minutes later, Cabading left his guest to go upstairs. Shortly afterward, a series of shots rang out, causing Nonilo to flee.

When policemen arrived at the scene, they found Lydia on Leonardo’s body, shielding him uselessly from the fatal gunshots that claimed her life. Sprawled on his daughter’s bed was Pablo, who had turned his own .45 caliber pistol on himself after his crazed rampage. Anunsacion was found on the floor, writhing in pain, the lone survivor of this family tragedy.

4. The Laurel-Silva Double Killing (1965)

Whenever a prominent political name is involved in a crime, expect newspapers to blare out headlines of the most sensational kind. Such was the case with Jaime “Banjo” Laurel, the son of then Cong. Jose B. Laurel. He was implicated as a suspect in the murder of his estranged wife, the beautiful Erlinda Gallegos-Laurel, and customs agent Amando V. Silva, her lover, on August 16, 1965.

READ: 11 Reasons Why Jose P. Laurel Was A Total Badass

Initial findings indicated murder-suicide at Laurel’s posh Paco apartment—Gallegos was shot 11 times by Silva, who then turned the gun on himself. Then, a murder angle was introduced, and a suspect, Feliciano Tinio Jr., was taken in for questioning.

New findings revealed a more chilling theory—parricide-murder. Thus, a case was filed against Linda’s husband, Banjo Laurel, already known for his ‘bad boy’ reputation, and four others. The trial was presided by Judge Jesus Morfe after the original judge, Juan Reyes, a Laurel relative, inhibited himself from the case.

Defending Banjo was his uncle (and future Philippine Vice President), Atty. Salvador Laurel. Atty. Laurel succeeded in ferreting out a crucial fact during his examination of the NBI witness: that the blood-stained bullet found on the ceiling of the crime scene was consistent with the trajectory found in the head of Silva. He also forced a witness to retract his confession who admitted to lying under torture.

Thus, Banjo was acquitted of the crime. He later joined politics (he became Tanauan mayor), a career cut short by his death in a helicopter crash in Camarines Sur on January 12, 1970.

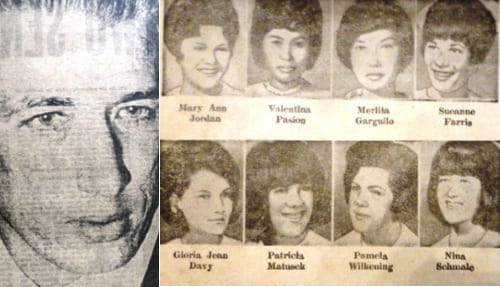

3. Richard Speck and the Student Nurse Murders (1966)

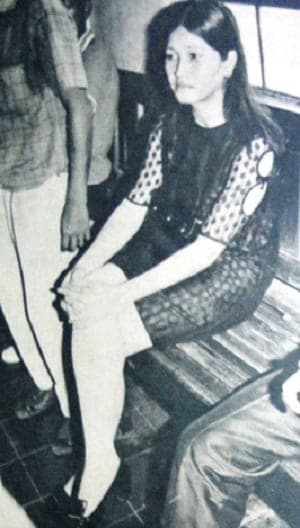

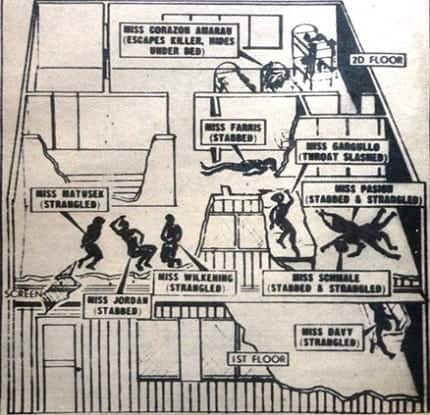

Although this bone-chilling crime was committed in Chicago, its far-reaching impact was felt most profoundly in the Philippines, as the sole survivor—and witness of this killing spree—was a Filipina exchange student nurse, Corazon Amurao of Batangas.

Richard Benjamin Speck, a 25-year-old drifter and drunkard with many criminal records had gone to Chicago to look for a job. Unsuccessful in his search, Speck spent his idle days drinking before accosting and raping Ella Mae Hooper, whose gun he also took.

At about 11 PM on July 13, 1966, Speck slipped into a nurses’ apartment house and knocked on the bedroom door of Amurao. Armed with a gun, Speck herded eight student nurses in a room—including Filipinas Merlita Gargullo and Valentina Pasion—and tied them. Speck then took them out one by one and proceeded to rape and kill them by stabbing and strangulation.

Amurao escaped death by hiding under a bed. Seven hours later, after Speck had left, Amurao got out of the room through a window and screamed for help.

Two days after, Speck was recognized in a bar; he then attempted suicide after sensing that the police were hot on his trail. He was arrested when he was taken to a hospital. Speck’s jury trial on April 3, 1967, brought him face to face with Amurao, who positively identified the killer. He was found guilty on April 15 and sentenced on June 5 to die in the electric chair.

Although the Illinois Supreme Court upheld his sentence in 1968, this was overturned due to jury selection issues. Speck died in 1991 of a heart attack; he had spent 25 years in prison. Amurao, on the other hand, returned to the Philippines to resume work in a university hospital, was elected as a town councilor, and became the wife of lawyer Alberto Atienza.

Amurao is happily settled in Virginia with her family, her heroic part in “America’s Crime of the Century” now but a blurry vision of her past.

2. The Crime Against Maggie’s Virtue (1967)

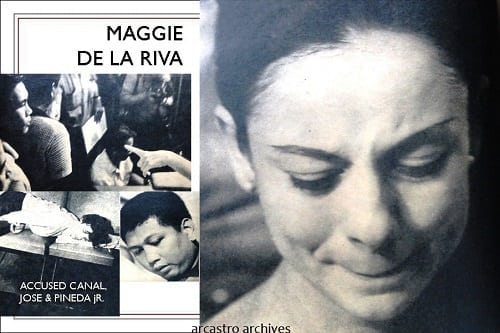

Magdalena Torrente de la Riva, or Maggie de la Rivera, was already a rising star in TV and films when the most despicable crime was committed against her virtue.

On June 26, 1967, en route back to her New Manila home from a TV appearance, she was intercepted by a group of young men from well-to-do families and forced out of her car. Blindfolded, she was taken to the Swanky Hotel in Pasay City, where the helpless 25-year-old was forced into humiliating acts before being tortured, punched, and then raped by Jaime Jose, Basilio Pineda, Jr., Eduardo Aquino, and Rogelio Cañal.

After the dastardly deed was done, the group dumped de la Riva in front of the Free Press building near Channel 5, where a taxi took her home. There, the sobbing Maggie told her mother of her rape by four men. A complaint was filed with the Quezon City Police under Tomas Karingal, and it was only a matter of time before the assailants were found.

Also Read: The Mysterious Life And Death of Pepsi Paloma

First to fall was Jose, arrested near his Makati home. He named his co-conspirators which resulted in the capture of Pineda, Jr. and Cañali in Taal, Batangas. Aquino, the fourth suspect, was apprehended shortly.

Brought to trial, the four suspects had a different version of their encounter with De La Riva, in which one of them, Pineda, “wanted to teach her a lesson” after she allegedly almost hit their car. He then offered her PHP 1,000 to do a striptease act, to which de la Riva supposedly complied. The court found this story incredulous and handed out a guilty verdict for the crime of kidnapping with rape.

Judge Lourdes San Diego meted death sentences by electrocution on October 2, 1967. The accused later appealed but lost, with the Supreme Court upholding the RTC decision in 1971.

On May 17, 1972, Jose, Pineda Jr., and Aquino were executed in the electric chair in Muntinlupa, despite a last-minute plea for mercy by Jose’s mother in Malacañang. The fourth convict, Cañal, had died of a drug overdose in 1971. Their deaths provided closure to the tragic De la Riva episode, considered one of the most sensational cases in the post-war Philippines.

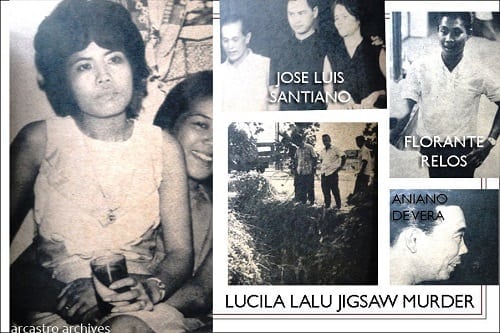

1. The Jigsaw Murder of Lucila Lalu (1967)

28-year-old Lucila Lalu was a probinsyana from Candaba who went to Manila in 1957 to try her luck in the big city. In a few years, she had become the common-law wife of policeman Aniano de Vera and had two businesses: Lucy’s House of Beauty and a nightclub, the Pagoda, in Sta. Cruz.

On May 28, 1967, Lalu disappeared, and two days later, policemen found her dismembered body in two separate areas—her torso along EDSA near the Guadalupe bridge and her legs at the corner of Rizal Ave., and Malabon St., Her head was nowhere to be found.

The initial suspects were rounded up: Florante Relos, a waiter at the Pagoda and Lalu’s lover; Aniano de Vera, the 42-year-old estranged partner who was the last person to see Lalu on May 28; and Jose Luis Santiano, a dental student boarder at Lalu’s parlor. Relos was released after finding no evidence against him, and de Vera was identified as the one with the strongest motive to kill Lalu–he had threatened her and Relos after discovering their affair.

Also Read: Top 10 Unsolved Mysteries in the Philippines

Then shockingly, two weeks after Lalu’s death, Santiano confessed to the crime to investigator Sgt. Ildefonso Labao. He alleged that on May 28, Lalu tried to seduce him. In rejecting her advances, Santiano claimed to have accidentally throttled her to death. Then, he chopped up her body and disposed of the parts, including her still-to-be-found head that he threw in a creek near Sct. Albano Q.C. The sloppy investigators had not bothered to check Santiano’s room because Labao said that “they did not consider it important.”

Two days later, Santiano recanted his confession, and the case was even more muddled when “mystery witness” Dr. Nora L. Ebio came forward to testify that Santiano was coerced by Labao into owning up to the crime.

When Santiano’s room was finally checked, the door was found to have been forced open, Found inside were bloodstains on the floor, a kitchen knife, razor blade, and a woman’s stockings—supposed pieces of evidence that the fiscal found so unconvincing, he had the NBI take over. Today, the Lalu chop-chop murder remains an open case.

References

“My Case Has Started A Revolution,” Maggie de la Riva as told to Jean Pope. (1967). Sunday Times Magazine, 18-22.

“The Dark at the Foot of the Stairs” (1965). Sunday Times Magazine, 34-39.

A Girl Named Annabelle. (1963). Sunday Times Magazine, 18-23.

Afuang, B. (1967). Heroine in a Real-Life Tragedy. Sunday Times Magazine, 26-31.

Crime and Punishment 1966. (1966). Sunday Times Magazine, 45.

Joaquin, N. (2009). Reportage On Crime: Thirteen Horror Happenings That Hit The Headlines (pp. 1-16). Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Maggie, A Rare Kind of Virtue. (1967). Sunday Times Magzine, 22.

Misa, A. (1969). Janet Clemente’s First Christmas at the Correctional. Sunday Times Magazine, 46-47.

Parungao, M. (1963). Flashback of RCA Robbery-Murder. Sunday Times Magazine, 38-41.

People of the Philippines, plaintiff, vs. Marlo Canial y Alimon, Alfredo Edwards y Contreras, and Janet Clemente y Hernandez, defendants., G.R. Nos. L-31042-31043 (Supreme Court 1972).

Pope, J. (1965). Rescued. Sunday Times Magazine, 18-23.

Pope, J. (1967). Life with Mother. Sunday Times Magazine, 18-20.

Reynolds, R. (1967). The Fight to Save Speck. Variety, 19-20.

Slaughter at Dawn. (1963). Sunday Times Magazine, 18-19.

The Manila Chronicle,. (1961). Cop Kills Daughter, Son-In-Law, Himself, p. Front Page.

The Palm Beach Post,. (1970). ‘Copter Crash Kills Jaime Laurel, Scion of Famous Philippines Family, p. B8. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/VVoKJ4

The Year of the Scar(e). (1965). Sunday Times Magazine, 34-35.

Zapanta, P. (1966). A Psychological Puzzler. Sunday Times Magazine, 18-19.

Zapanta, P. (1967). Luckless Lucila and her House of Horrors. Sunday Times Magazine, 10-15.

Zapanta, P. (1967). The Barrio’s Lucia to the City’s Lucila. Sunday Times Magazine, 18-19.

Alex R. Castro

Alex R. Castro is a retired advertising executive and is now a consultant and museum curator of the Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, Angeles City. He is the author of 2 local history books “Scenes from a Bordertown & Other Views” and “Aro, Katimyas Da! A Memory Album of Titled Kapampangan Beauties 1908-2012”, a National Book Award finalist. He keeps 2 pop culture blogs: “Views from the Pampang” (2009 Philippine Blog Awards finalist) and Manila Carnivals 1908-1939. He is a 2014 Most Outstanding Kapampangan Awardee in the field of Arts. For comments on this article, contact him at [email protected]

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net