11 Things You Never Knew About Gregorio Del Pilar

In his early 20’s, General Gregorio del Pilar (also known as “Goyo”) was just as love-struck as most people his age.

But he was also on the battlefield, never letting romance get in the way of his obligation to our country. In fact, his death at the age of 24 is a perpetual reminder that heroism knows no age.

As we celebrate the release of “Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral” movie, let’s pay tribute to the real Gregorio del Pilar, an intriguing historical figure who blurs the line between a hero and a villain.

Also Read: 13 Facts That Prove Antonio Luna Was An All-Around Badass

1. The Badass General Had a Badass Childhood

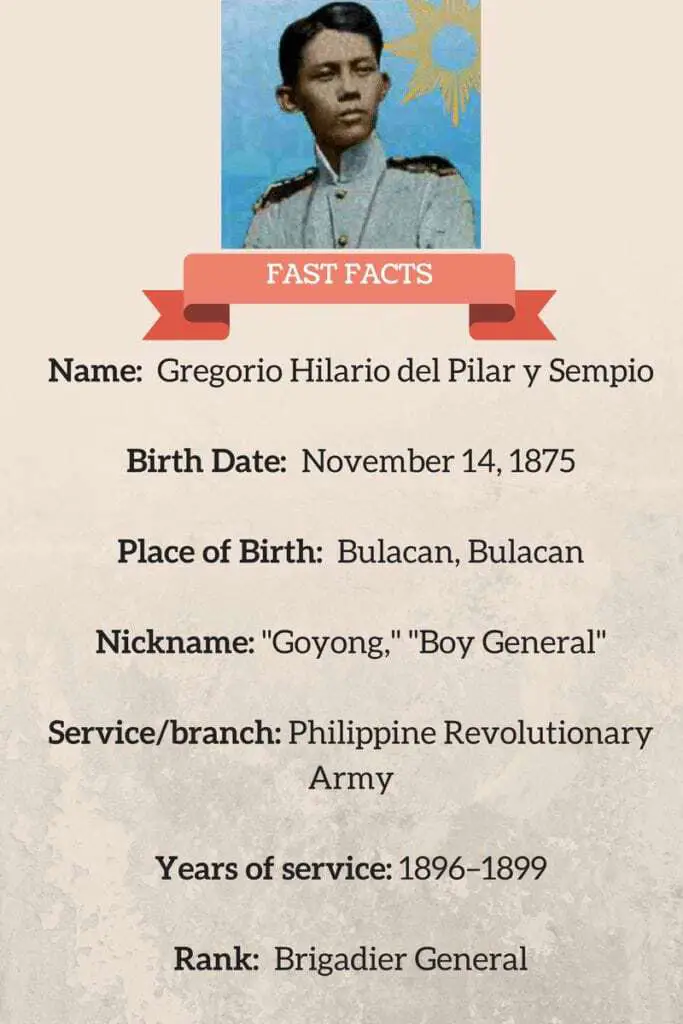

Born on November 14, 1875 to Bulakeño parents Felipa Sempio and Fernando del Pilar, Goyo was fortunate enough to learn combat skills at such an early age.

While his contemporaries only learned things within the confines of their classroom, the young Goyo was already being conditioned for a life in the battlefield. An expert taught him the Philippine martial art called “arnis de mano” which uses a stick or bladed weapon in fighting.

Biographer Isaac Cruz shared this interesting snippet of Goyo’s early years:

“Katipuneros fondly recalled a duel between the 12-year-old Gregorio and 37-year-old Marcelo H. Del Pilar (his uncle). The young Goyo displayed his expertise in his offensive thrusts with Marcelo displaying his marvelous self-defense techniques. The duel ended in a draw.”

Goyo was also a formidable hunter: Using a blowgun made of buhong bocaue, he would shot down birds almost spontaneously while “riding on a banca or on the back of a carabao.” These stories seem trivial, but they give us a peek to how Goyo grew up to become one of Aguinaldo army’s greatest assets.

Also Read: 7 Traditional Filipino Games You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

2. Gregorio del Pilar as a Secret Messenger

From being a meat pie vendor, the poor boy from Bulacan became a bonafide student of Ateneo de Manila with the help of his principalia relatives.

During this period, the young Goyo stayed at the house of his favorite aunt, Hilaria del Pilar, who happened to be the wife of propagandist and the first Supremo of the Katipunan–Deodato Arellano.

The secret society was founded in 1892 and Goyo first served as a secret messenger who would distribute pamphlets written by Filipino reformers in Europe.

READ: 25 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Jose Rizal

Once there was an anti-revolutionary pamphlet entitled “Questions of Great Interest” published by an Augustinian friar. For some reason, Goyo and his companions were able to access the sacristy of the Malolos church and secure copies of the said pamphlets.

They then removed the cover and placed them in the satirical Filipino pamphlets which originally carried the titles “The Vision of Fr. Roriguez,” “By Telephone,” “Prayers and Jokes” (Dasalan at Toksohan), “Kai-igat Kayo,” etc.

When the parish priest distributed the booklets to the congregation and even encouraged them to read it, little did he know that he was actually shooting himself in the foot. In other words, their plan to discredit the Propaganda Movement backfired–all because of Goyo’s shrewdness.

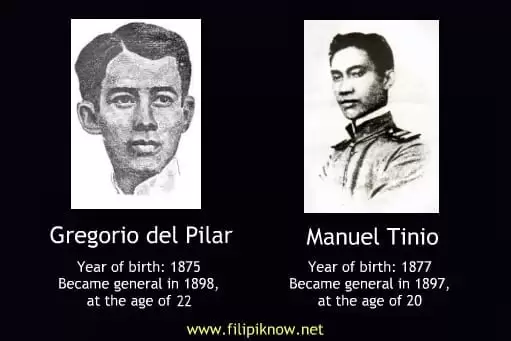

3. Gregorio del Pilar was NOT the Youngest General in Aguinaldo’s Army

Contrary to popular belief, Gregorio del Pilar was not the youngest general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army. The distinction belongs to Manuel Tinio, known by his Katipunan pseudonym Magiting.

Tinio hadn’t even completed his high school education when he joined the Katipunan. In fact, the young boy from Nueva Ecija was not given initial responsibilities in the secret society because he was too young at the time of his joining.

But Tinio never let his youth incapacitate him: he first fought in the field in 1897, and it was also in the same year when Aguinaldo promoted him to the rank of brigadier-general, at the tender age of 20.

Also Read: 5 Historic Lies You Were Taught In School

In contrast, Goyo was only appointed lieutenant colonel in 1897, after a successful raid in the town of Paombong, Bulacan. Almost a year later, he finally earned the title of full general as a reward for his key role in helping liberate Bulacan and Nueva Ecija from the Spaniards. Goyo was then a few months shy of his 23rd birthday.

4. The “Aguila” meets “Matanglawin.”

On March 15, 1896, Goyo received his Bachelor of Arts degree from the Ateneo de Manila. We can only wonder what would have happened had the 21-year-old Bulakeño pursued his post-grad plan of enrolling at the School of Arts and Trades to be a maestro de obras (foreman).

As it turned out, 1896 was coincidentally the year the Philippine Revolution erupted, and Goyo decided to enlist himself in the Katipunan instead. Lt. Jose Enriquez, Goyo’s close friend and one of only eight survivors of the Battle of Tirad Pass, recalled how the boy general became part of the secret society:

“Goyo signed an oath with his own blood, promising to support the society, keep its secrets, obey its laws and aid its comrades. His hand quivered as he wrote his nom de guerre: Aguila. After the rites, the Supremo (Deodato Arellano) approached his nephew and said: “Like the Aguila, be vigilant. It is the price of liberty!”

Interestingly, Enriquez’s older brother, Anacleto (known for his pseudonym Matanglawin or hawk’s eye), was someone whom Goyo looked up to and considered his “idol.”

Anacleto was Bulacan’s father of Katipunan who unfortunately died after he and his group were cornered in a San Rafael church by Spanish riflemen. The battle is so gruesome that the church was said to be “ankle deep” in blood.

5. Goyo and the “Seven Musketeers.”

Goyo’s baptism of fire happened when he became part of Gen. Eusebio Roque’s troops in Kakarong de Sili, a fortress near San Rafael, Bulacan.

Joining del Pilar was a group of young men, also known as the “Seven Musketeers of Pitpitan”: Julian, Goyo’s older brother; Juan Socorro, his brother in law; Juan Mendez Catindig; Felix de Jesus; Melencio Manahan; Adeodato Manahan; and Isidro Wenceslao.

Kakarong had been recognized as the biggest headquarters in Bulacan until an attack of the Spaniards in 1897 led to its collapse.

The Battle of Kakarong caught the Katipuneros by surprise, but Goyo and the rest of the musketeers fought up to the last minute. Upon realizing that they were clearly outnumbered, Goyo and the other survivors decided to escape.

Among the fatalities of that bloody battle was Juan Mendez Catindig, one of the seven musketeers.

Goyo missed death when a Mauser bullet only grazed to his forehead. Appointed lieutenant for his bravery, the young officer then led his men to Montalban before returning to Bulacan.

Back to his home province, Goyo and his group ambushed several cazadores who were escorting a friar back to Malolos. A cazadore was shot and killed by Goyo, while the friar and the rest of his entourage managed to escape.

The Spaniards left behind four sacks of silver coins and a Mauser, much to the delight of del Pilar who had only owned a Remington before the encounter.

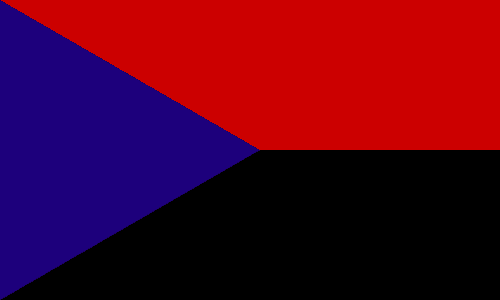

6. Gregorio Del Pilar’s Flag Gave Birth to Today’s Philippine Flag

Fresh from their successful raid in Paombong, the newly-appointed Lieutenant Colonel Gregorio del Pilar celebrated the double victory by designing a flag for his troops.

Del Pilar’s flag was inspired by Cuban’s and consisted of three colors–blue, red, and black. It was first used by Goyo’s battalion at Pasong Balite in Polo, Bulacan and has been considered as the precursor of today’s Philippine national flag.

In 1975, then Bulakan Municipal Secretary Luisito Osorio paid tribute to Goyo and his flag during the fallen hero’s 100th birthday:

“Del Pilar’s flag is unique in that it is strictly neither a Katipunan War Standard nor a mere variation of the first Philippine Flag. As a matter of fact, it is an intermediary between the latter and our present national flag. Incidentally, it should not be confused with the flag designed by Gen. Pio del Pilar and used by the Balangay “Magtagumpay” of the Katipunan.”

7. The Playboy and His (many) Girlfriends

Had he not died early, Heneral Goyo would have rivaled Rizal for the title “playboy of Philippine history.” But what is it about Goyo that women of his time easily fell head over heels in love with him?

In addition to his military prowess at such a young age, the boy general’s physical attributes were equally pleasing, as described by his friend Rafael Palma:

“He had agreeable and genial features. He was above the average in height, with clear pinkish brown skin, with somewhat brown eyes, straight nose, thin lips, slender body–he may be considered a handsome fellow to all intents and purposes.”

According to historian Teodoro Kalaw, Goyo and his troops were in Dagupan from June to November of 1899. It was here when the boy general became vainer than ever: he ordered the best horses and showed off his horsemanship for all the girls to see.

One lady, in particular, caught his eyes: Dolores Nable Jose, a pretty heiress whom he actually looked forward to marrying as soon as the war ended.

READ: The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in Philippine History

Dolores came to be known as Goyo’s great last love–her name embroidered in a handkerchief recovered by the Americans from Del Pilar’s lifeless body in Tirad Pass.

However, in a 1965 Philippine Free Press article entitled “Remembering del Pilar,” biographer and historian Carlos Quirino revealed that the young general’s sweetheart was actually named Remedios Nable Jose, not Dolores.

Turns out, Dolores was Remedios’ younger sister who almost refused to give her handkerchief as a souvenir because it’s dirty and she’s having colds at that time. Goyo insisted and put the handkerchief in his pocket, “saying he valued it more in that condition.”

Remedios was only 17 when she met the 24-year-old Goyo. She described him as a “very romantic young man” and recounted a romantic moment they had one night: “He pointed to a particularly bright star and asked me to look at it always after he had left that town because he would be doing the same and thinking of me. The star, he said, would be ours, and ours alone!”

According to Remedios, who was 83 at the time of the interview, she almost tied the knot with General Goyo but backed out at the last minute primarily because of the latter’s “playboy” reputation.

Before Remedios, there were numerous young women who captivated the boy general’s heart. After all, historians often describe him as a “Romeo with a Juliet in every town.”

Among those who became Juliets of Philippine Revolution’s Romeo were: Neneng Rodrigo, daughter of Bulacan’s first Filipino civil governor and also Goyong’s first love; a sister of Col. Leyva; and Felicidad Aguinaldo, the younger sister of Gen. Aguinaldo who reportedly knelt, prayed, and wept at the exact spot where the young general died in Tirad Pass.

The most intriguing of Goyong’s love affairs was with a certain “Poleng” whom he addressed in several drafts of love letters written sometime in 1895 when he was 20. While Poleng’s true identity will probably remain a mystery, it is known that her affair with Goyo was cut short because her mother was against it.

Some people find Goyo’s love life fascinating, but for some historians, it paints a picture of how distracted and unconcerned the young general was to the real cause of the Revolution.

8. Gregorio del Pilar and the Schurman Commission

In 1899, the Malolos Government was clearly divided. While others such as Mabini and Luna encouraged Filipinos to continue fighting the Americans, turncoats like Paterno and Buencamino believed more in accepting America’s offer of autonomy.

Power play ensued and Mabini was soon relieved as President of the Cabinet with Paterno taking over the role.

The new Cabinet leader then appointed Buencamino as the head of the peace commission, much to the dismay of Gen. Luna. He accused Buencamino of being a traitor and even slapped the latter in front of other officials.

The scandal led to the suspension of the commission and the appointment of a new one composed of Gen. Gregorio del Pilar, Captain Lorenzo Zialcita, Alberto Barretto and Gracio Gonzaga.

The first peace commission could have been represented by someone more senior than Del Pilar (he was only 23 years old at that time) but his appointment by Aguinaldo only proves that favoritism prevailed in the Philippine army.

Del Pilar and the other members of the Filipino panel negotiated for an armistice with the Schurman Commission in May 1899.

The Americans proposed a government wherein the governor general would be appointed by the president and “the heads of departments and judges to be either Americans or Filipinos, or both.”

On the other hand, the Filipinos, through Gen. del Pilar, said that they were “anxious to surrender” because “if we give up our arms we are at the complete mercy of the Americans.”

In the end, both parties refused to compromise and the Filipinos had no choice but to continue their struggle for independence.

9. Gregorio Del Pilar As Antonio Luna’s Almost-Assassin

If we are to believe not-so-mainstream history books like Nick Joaquin’s “A Question of Heroes,” then Goyo was indeed Aguinaldo’s hatchet man.

It is said that the boy general and his master met in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija just a few weeks after their futile attempt to negotiate with the Schurman Commission. It was here where General Aguinaldo gave his protégé the difficult task of capturing Gen. Antonio Luna–who was accused of “high treason”–dead or alive.

But as it turned out, Luna had already been killed by the Presidential Guards in Cabanatuan before Goyo and his troops could reach Luna’s headquarters in Pangasinan.

Also Read: 10 Mind-Blowing Controversies Of Philippine History

In a 1985 biography about the boy general, Isidro Wenceslao, one of Del Pilar’s men and survivors of the Battle of Tirad Pass, recalled how he was approached by the Del Pilar brothers a few days before Luna’s assassination:

“Do you know Gen. Antonio Luna?” the general asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“He is wanted, dead or alive for High Treason!”

General Venancio Concepcion, one of Luna’s officers who was relieved of his command after the assassination in Cabanatuan, also claimed that he was interrogated for the alleged conspiracy against Aguinaldo.

It is also said that soon after Luna’s death, Gen. Gregorio del Pilar led his men in taking “possession of Luna’s headquarters in Bayambang” and in the killing of Luna’s security escorts–brothers Manuel and Jose Bernal.

For his accomplishments, the boy general was greatly rewarded: he was appointed commandant general of Pangasinan by no less than Aguinaldo.

10. His Death was NOT as Epic As we Thought

From Dagupan, Gen. Goyo and his 200 selected officers traveled to Tirad Pass in Ilocos Sur in a brave attempt to prevent the Americans from capturing Aguinaldo.

Little known is the fact that the president twice begged Goyo to remain in Cervantes supposedly after seeing an “ominous sign on a tuft of mane that twisted upward.” But the stubborn Del Pilar continued his journey, unaware that he was about to meet his end.

Also Read: 22 Things You Didn’t Know About ‘Heneral Luna’

On December 2, 1899, Goyo and his men clashed with 1,000 soldiers of Major March (the number of which was later reinforced) in the legendary Battle of Tirad Pass.

Just when the Filipino troops thought their position was working to their advantage, a Filipino spy-guide betrayed his countrymen by showing the Americans a secret path leading to the top of the hill. And this was how Gen. del Pilar became an easier target for the Americans.

There are two versions of how Gen. Goyo actually died, one of which came from American war correspondents such as Richard Henry Little:

“I saw him arraign his soldiers from trench to trench, excite their amor propio, to ponder their valor and love of country, mount his white horse in the midst of bullets from our Krag rifles. Then I saw one of our soldiers below, turn his way….climb a rock and aim his rifle at Gen. del Pilar. We held our breath, not knowing whether to pray God that the soldier hit or miss his mark.”

American newspapers had to make the story more dramatic, but nothing could be further from the truth. Based on the accounts of two eyewitnesses from the Philippine army, it was curiosity that killed the boy general.

READ: 11 Things From Philippine History Everyone Pictures Incorrectly

Vicente Enriquez, one of the survivors of the battle, said that after he and the general went to higher trenches, Del Pilar tried to spot enemies in hiding but couldn’t see past the cogon leaves which were moving irregularly.

The general was about to mount his pinkish white horse when he was hit by “a bullet from behind, at the nape of his neck, just below the level of his mouth.”

The other eyewitness account, by Telesforo Carrasco (a Spaniard in Aguinaldo’s army), shared almost the same details as Enriquez’s:

“The general could not see the enemy because of the cogon grass and he ordered a halt to the firing. At that moment I was handing him a carbine and warning him that the Americans were directing their fire at him and that he should crouch down because his life was in danger and at that moment he was hit by a bullet in the neck that caused instant death.”

11. Whatever happened to General Gregorio del Pilar’s remains?

Only eight from the Filipino troops survived the bloodbath at Tirad Pass.

The lifeless body of Del Pilar was stripped of clothing. All his belongings–including his diary, shoes, brand new uniform, medallions, and a handkerchief embroidered with his alleged lover’s name–were stolen by Americans who kept them as souvenirs.

For many years, many believed that the body of Del Pilar was either left to rot or given a hero’s burial by American Lt. Dennis P. Quinlan who greatly admired the boy general. The second theory raised some eyebrows because the area around where the general died is basically made of granite rock and it would have taken several weeks–and several men–to bury the body.

It was only in 1929 when the mystery was finally solved.

Manuel (nicknamed “Abeng”) and Bonifacio (nicknamed “Tucdaden”) personally knew the general and were among those who buried him and the other dead Katipuneros. With the help of these two eyewitnesses, the national committee led by then Ilocos Sur Governor Alejandro Quirolgico was able to exhume Goyo’s remains.

The said remains were then examined thoroughly before finally being proven to be that of the fallen general. Among the discoveries that proved the authenticity of Goyo’s remains was the presence of a gold tooth. As it turned out, Gen. del Pilar had his one tooth filled with gold when he was in Hong Kong in 1897.

Dr. Sixto de los Angeles, the same medico-legal expert who examined the now-missing bones of Bonifacio, also concluded that the remains found in Tirad Pass belong to a Filipino male between 20 and 25 years old.

All the evidence proved “with absolute authority and without doubt” that the remains–which were later brought to the National Museum in 1930–are really those of Gen. Gregorio del Pilar.

Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral (Official Trailer)

READ: 22 Things You Didn’t Know About ‘Heneral Luna’

References

Agoncillo, T. (2012). History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: C & E Publishing, Inc.

Cruz, I. (1985). Gregorio H. Del Pilar: Idol of the Revolution. Samahang Pangkalinangan ng Bulakan, Bulakan.

De Ocampo, E. (2010). The Role of Gregorio del Pilar and Emilio Jacinto in Philippine History. The Journal Of History.

Foronda, M. (2010). Gregorio del Pilar: An Appraisal. The Journal Of History.

Joaquin, N. (2005). A Question of Heroes. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Ocampo, A. (2000). Uncompromising stands: Luna, Mabini. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. 9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/sDGVee

Ocampo, A. (2003). Del Pilar’s bones. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A15. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/9Wzftg

Ochosa, O. (1989). The Tinio Brigade: Anti-American Resistance in the Ilocos Provinces 1899-1901. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers.

The Clinton Morning Age,. (1899). An Offer To Filipinos, p. Front Page. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/Fm17o1

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net