Precolonial Period in the Philippines: 18 Facts You Need To Know

While Filipinos nowadays are pretty knowledgeable about the Spanish, American, and Japanese eras, the same cannot be said regarding the precolonial period in the Philippines. This is a shame because even before the three foreign races came, our ancestors lived in a veritable paradise.

Also Read: 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History

Although it wasn’t perfect, that era was the closest thing we ever had to a Golden Age, a sentiment shared by national hero Jose Rizal, members of the Katipunan, noted historian Teodoro Agoncillo, and even some church historians.

Let’s look at some of the most interesting facts about the precolonial period in the Philippines and compelling reasons why we think life was better during this period in our nation’s history.

Table of Contents

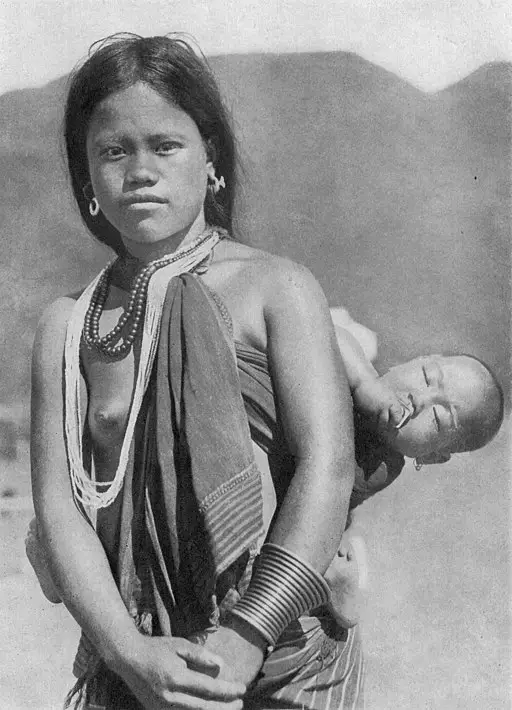

1. Women Enjoyed Equal Status With Men

During pre-colonial times, women shared equal footing with men in society. They were allowed to divorce, own and inherit property, and even lead their respective barangays or territories.

In matters of family, the women were the working heads, possessing the power of the purse and the sole right to name their children. They could dictate the terms of their marriage and even retain their maiden names if they chose to do so.

During this time, people traced their heritage to their fathers and mothers. It could be said that the precolonial period in the Philippines was largely matriarchal, with the opinions of women holding a significant weight in matters of politics and religion (they also headed the rituals as the babaylans).

As a show of respect, men were even required to walk behind their wives. This largely progressive society that elevated women to such a high pedestal took a serious blow when the Spanish came. Eager to impose their patriarchal system, the Spanish relegated women to the homes, demonized the babaylans as satanic, and ingrained into our forefathers’ heads that women should be like Maria Clara—demure, self-effacing, and powerless.

2. Society Was More Tolerant in Pre-Colonial Philippines

While it could be said that our modern society is one of the most tolerant in the world, we owe our open-mindedness not to the Americans and certainly not to the Spanish but to the pre-colonial Filipinos.

Sexuality was not as suppressed, and no premium was given to virginity before the marriage. Although polygamy was practiced, men were expected to do so only if they could support and love each of their wives equally.

Homosexuals were also largely tolerated, as some babaylans were men in drag.

Back then, there were no doctors or priests our ancestors could turn to when things went awry. Their only hope was a spirit medium or shaman who could directly communicate with the spirits or gods. They were known in the Visayas as babaylan, while the Tagalogs called them catalonan (katulunan).

Also Read: The first same-sex marriage in the Philippines

More often than not, these babaylans or catalonans were women who came from prominent families. However, early Spanish missionaries reported men who assumed the role of a babaylan. That also suggests that these male versions may have existed long before the Spaniards arrived.

What’s more surprising is that some of these male babaylans dressed and acted like women. Visayans called them asog while the Tagalogs named them bayugin. In the 1668 book Historia de los Islas y Indios de Bisayas, Father Francisco Alcina further described an asog as:

“…impotent men and deficient for the practice of matrimony, considered themselves more like women than men in their manner of living or going about, even in their occupations….”

The 16th-century manuscript Boxer Codex added even more intriguing details:

“The bayog or bayoguin are priest dressed in female garb……Almost all are impotent for the reproductive act, and thus they marry other males and sleep with them as man and wife and have carnal knowledge.”

As time passed, the term asog has taken on completely different meanings. In Aklan, for example, asog is now used to refer to a tomboy or a woman acting like a man.

Surprisingly, with the amount of sexual freedom, no prostitution existed during the pre-colonial days. Some literature suggests that the American period—which heavily emphasized capitalism and profiteering—introduced prostitution into the country on a massive scale.

3. The People Enjoyed a Higher Form of Government

The relationship between the ruler and his subjects was straightforward back then: In return for his protection, the people paid tribute and served him in times of war and peace.

Going by the evidence, we could say that our ancestors already practiced an early version of the Social Contract, a theory by prominent thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which espoused the view that rulers owe their right to rule based on the people’s consent.

Conversely, if the ruler became corrupt or incompetent, the people had a right to remove him. And that’s precisely the kind of government our ancestors had. Although the datus technically came from the upper classes, he could be removed from his position by the lower classes if they found him wanting of his duties. Also, anyone (including women) could become the datu based on their merits, such as bravery, wisdom, and leadership ability.

4. We Were Self-Sufficient

In terms of food, our forefathers did not suffer from any lack thereof. Blessed with such a resource-rich country, they had enough for themselves and their families.

Forests, rivers, and seas yielded plentiful meat, fish, and other foodstuffs. Later on, their diet became more varied, especially when they learned to till the land using farming techniques that were quite advanced for their time. The Banaue Rice Terraces are one such proof of our ancestors’ ingenuity.

READ: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

What’s more, they already had an advanced concept of agrarian equity. Men and women equally worked in the fields, and anyone could till public lands free of charge. Also, since they had a little-to-no concept of exploitation for profit, our ancestors generally took care of the environment well.

Such was the abundance of foodstuffs that Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, the most-successful Spanish colonizer of the islands, was said to have reported the “abundance of rice, fowls, and wine, as well as great numbers of buffaloes, deer, wild boar, and goats” when he first arrived in Luzon.

5. Gold Was Everywhere

There was plenty of gold in the islands during the precolonial period in the Philippines, and it used to be part of our ancestors’ everyday attire.

In the book by historian William Henry Scott, it was said that a “Samar datu by the name of Iberein was rowed out to a Spanish vessel anchored in his harbor in 1543 by oarsmen collared in gold; while wearing on his own person earrings and chains.”

Much of the gold artifacts recovered in the country are believed to have come from the ancient kingdom of Butuan, a major center of commerce from the 10th to the 13th century. Ancient Indian texts also suggest that merchant ships used to trade with people from what they called Survarnadvipa or “Islands of Gold,” believed by many as present-day Indonesia and the Philippines.

Related Article: Pinoy chef made the world’s most expensive sushi! – Covered with gold, diamonds

Precolonial treasures include ear ornaments called panika; bracelets known as kasikas; and the spectacular serpent-like gold chain called kamagi. Since their discovery, some of these valued gold artifacts have been looted, melted, and sold.

It didn’t matter to the treasure hunters that these gold ornaments were originally part of our ancestors’ bahandi (heirloom wealth) and probably originated here and in other places they traded with.

6. We Had Smoother Foreign Relations

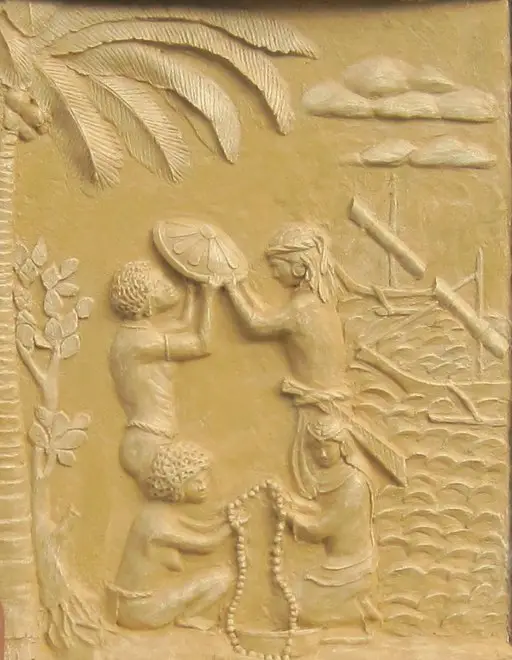

We’ve all been taught that before the Spanish galleon trade, the pre-colonial Filipinos had already established trading and diplomatic relations with countries as far away as the Middle East.

Instead of cash, our ancestors exchanged precious minerals, manufactured goods, etc., with Arabs, Indians, Chinese, and other nationalities. Many foreigners permanently settled here during this period after marveling at the country’s beauty and people.

Out of the foreigners, the Chinese were most amazed at the pre-colonial Filipinos, especially regarding their extraordinary honesty. Chinese traders often wrote about the Filipinos’ sincerity and said they were one of their most trusted clientele since they did not steal their goods and always paid their debts.

Out of confidence, some Chinese were known to leave their items on the beaches to be picked up by the Filipinos and traded inland. When they returned, the Filipinos would give them back their bartered items without anything missing.

7. We Built Warships That Could “Sail Like Birds”

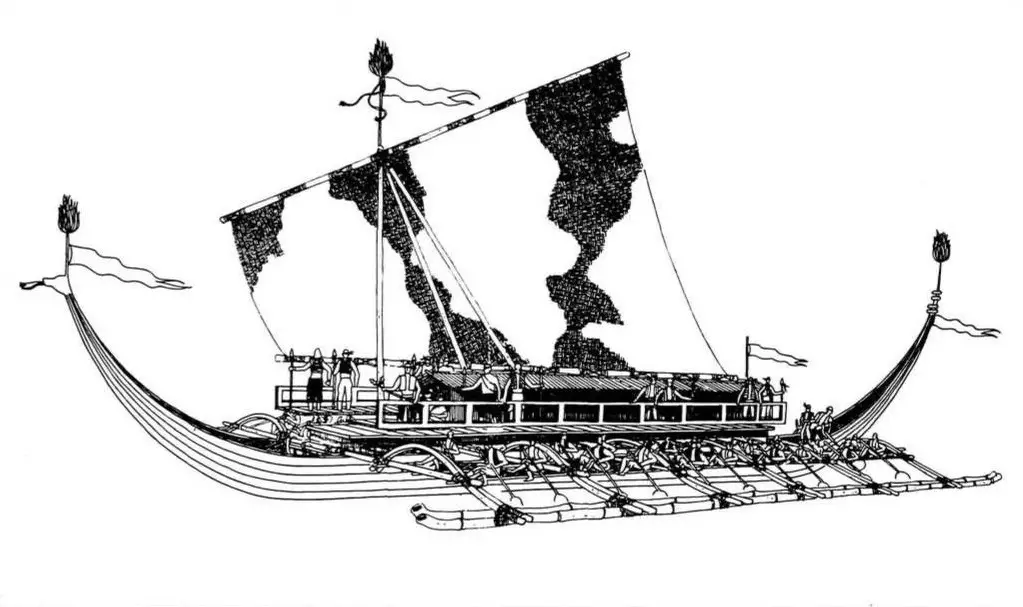

They may be primitive, but our ancestors made the most of what they had and created amazing marine architecture. The Visayan warship karakoa was the result of such ingenuity.

Note that our early plank-built vessels were made in the same tradition as other boats dating back to 3rd century BCE. And that probably explains why our karakoa is similar to Indonesia’s korakora.

In his paper “Boat-Building and Seamanship in Classic Philippine Society,” historian William Henry Scott described the karakoa as “sleek, double-ended warships of low freeboard and light draft with a keel on one continuous curve……and a raised platform amidships for a warrior contingent for ship-to-ship contact.”

The karakoa served not only as a warship but also as a trading vessel. Accounts from the 1561 Legazpi expedition described it as “a ship for sailing any place they wanted.”

And sailed they did, reaching places as far as Fukien coast in China where a bunch of Visayan pirates pillaged the villages sometime in the 12th century.

The flexibility of its plank-built hull and the coordination of a hundred or so paddlers all helped karakoa generate its best speed of 12 to 15 knots–three times the speed of a Spanish galleon. It was so efficient that Fr. Francisco Combés once wrote it could “sail like birds.”

8. Our Forefathers in the Pre-Colonial Philippines Already Possessed a Working Judicial and Legislative System

Although not as advanced (or as complicated) as our own today, the fact that our ancestors already possessed a working judicial and legislative system shows that they were well-versed in the concept of justice.

Life in the pre-colonial Philippines was governed by a set of statutes, both unwritten and written, and contained provisions concerning civil and criminal laws. Usually, it was the datu and the village elders who promulgated such laws, which were then announced and explained to the people by a town crier called the umalohokan.

Related Article: 9 Philippine Government Agencies That Need To Reform Right Now

The datu and the elders also acted as de facto courts in case of disputes between individuals of their village. In the case of inter-barangay disputes, a local board composed of elders from different barangays would usually act as an arbiter.

Penalties for anyone guilty of a crime include censure, fines, imprisonment, and death. As we’ve said, the system was imperfect, but it worked.

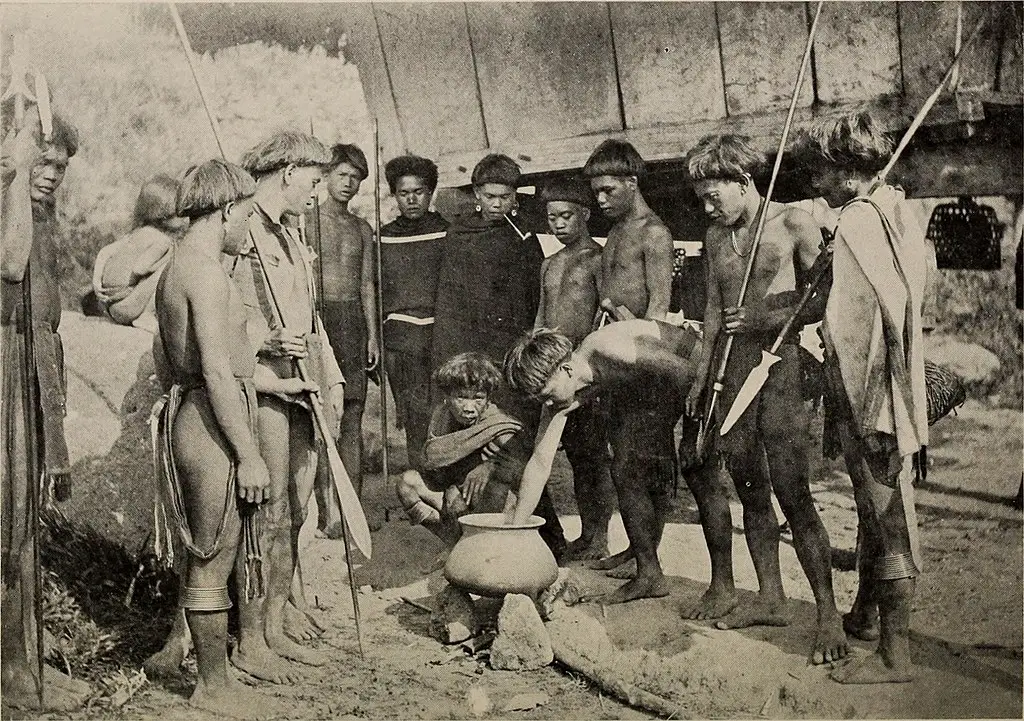

Tortures and trials by ordeal during this time were also common. You may have encountered “trial by ordeal” while reading stories from medieval Europe. It’s a method of judgment wherein an accused party would be asked to do something dangerous. If he luckily survives, he would be considered innocent. Otherwise, he would be proclaimed guilty.

Our ancestors–and even some of today’s indigenous peoples–had a similar custom. The difference is that our version didn’t usually end up in a life-or-death situation.

READ: 6 True Stories From Philippine History Creepier Than Any Horror Movie

The Ifugao, for example, subjected the involved parties to either a “hot water” or “hot bolo” ordeal. The former involved dropping pebbles in a pot filled with boiling water. The accused was then asked to dip his hands into the pot and remove the stones. Failure to do this or doing it with “undue haste” would be interpreted as a confession of guilt.

As the name suggests, the “hot bolo” ordeal required both suspects to have their hands touched by a scorching knife. The one who suffered the most burns would be declared guilty.

Other methods included giving lighted candles to the suspects; the guilty party was the one whose candle died off first. There’s also one which asked both persons to chew rice and later spit it out, the guilty person being the one who spits the thickest saliva.

9. They Had the Know-How To Make Advanced Weapons

Our ancestors—far from being the archetypal spear-carrying, bahag-wearing tribesmen we picture them as— were proficient in war. Aside from wielding swords and spears, they also knew how to make and fire guns and cannons. Rajah Sulayman, in particular, was said to have owned a huge 17-foot-long iron cannon.

Aside from the offensive weapons, our ancestors also knew how to construct massive fortresses and body armor. For instance, the Moros living in the south often wore armor that covered them head-to-toe. And yes, they also carried guns with them.

With all these weapons at their disposal and the fact that they were good hand-to-hand combatants, you’d think that the Spanish would have had a more challenging time colonizing the country. Sadly, the Spanish cleverly exploited the regionalist tendencies of the pre-colonial Filipinos. This divide-and-conquer strategy would be the primary reason why the Spanish successfully controlled the country for more than 300 years.

10. Several Professions Already Existed

Aside from being farmers, hunters, weapon-makers, and seafarers, the pre-colonial Filipinos also dabbled—and excelled—in several other professions.

To name a few, many became involved in such professions as mining, textiles, and smithing. Owing to the excellent craftsmanship of the Filipinos, locally-produced items such as pots, jewelry, and clothing were highly-sought in other countries. It is reported that products of Filipino origin might have even reached as far away as ancient Egypt. Clearly, our ancestors were very skilled artisans.

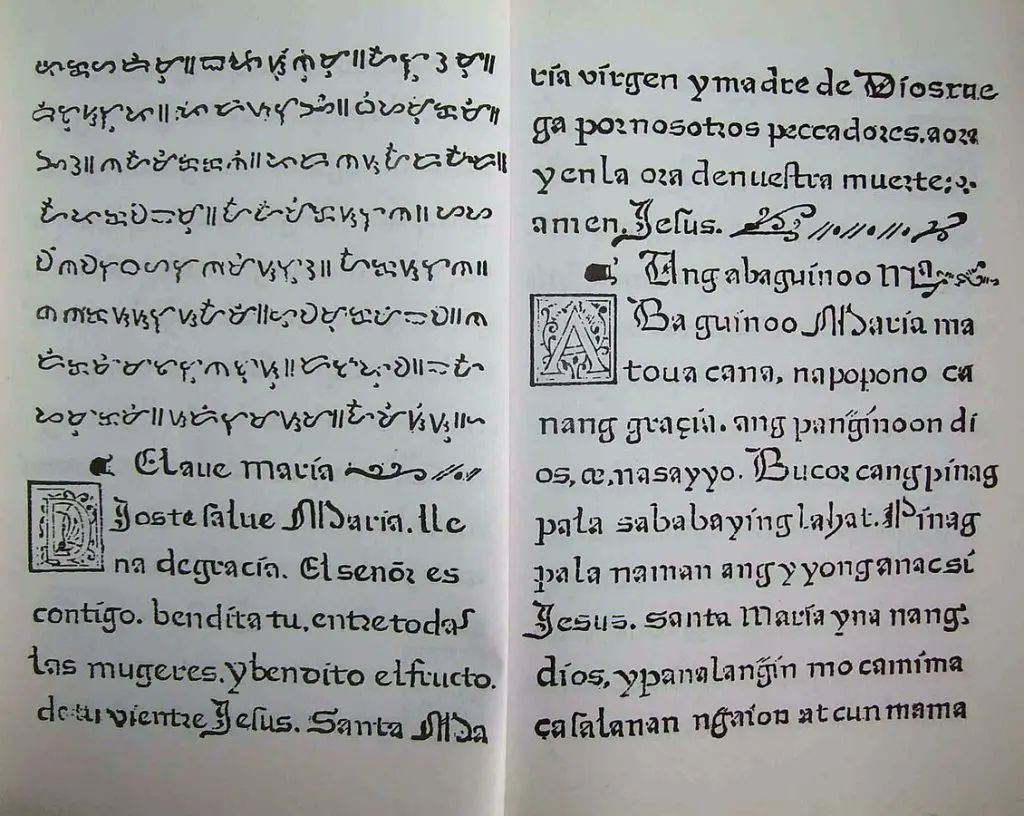

11. We Had Our Own Writing System

Using the ancient system of writing called the baybayin, the pre-colonial Filipinos educated themselves very well, so much so that when the Spanish finally arrived, they were shocked to find out that the Filipinos possessed a literacy rate higher than that of Madrid!

Father Chirino observed that there is “hardly a man, and much less a woman, who does not read and write,” while Morga wrote that there were very few who “do not write it (baybayin) very well and correctly.”

The baybayin is believed to be one of the indigenous alphabets in Asia that originated from the Sanskrit of ancient India.

Composed of 17 symbols, the ancient baybayin has survived in a few artifacts and Father Plasencia’s Doctrina Christiana en lengua Española y Tagala, the only example of the baybayin from the 16th century.

As to why the baybayin quickly disappeared, there are a few possible reasons. First, we were unlike China, which was miles ahead in writing and record-keeping. Instead, our ancestors used anything they could get their hands on as their writing pad (leaves, bamboo tubes, the bark of trees, you name it), while pointed weapons or saps of trees served as their ink.

The Boxer Codex also suggests that the content of whatever our ancestors wrote was relatively insignificant: “They have neither books nor histories nor do they write anything of any length but only letters and reminders to one another.”

Of course, the Spaniards also contributed to the early death of our ancient syllabic writing. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo believed so: “Aside from the destructive work of the elements, the early Spanish missionaries, in their zeal to propagate the Catholic religion, destroyed many manuscripts on the ground that they were the work of the Devil himself.”

12. They Compressed Their Babies’ Skulls for Aesthetic Reasons

In the ancient Visayas, being beautiful could be as simple as having a flat forehead and nose. But since humans are not usually born with these features, the Visayans used a device called tangad to achieve them.

The tangad was a comb-like set of thin rods that was put above the baby’s forehead, surrounded by bandages, and fastened at some point behind. Babies’ skulls are the most pliable, so this continuous pressure often results in elongated heads.

Some of these deformed skulls were recovered from various burial grounds in the Visayan region. Two are on display today at the Aga Khan Museum in Marawi.

Upon close examination of these skulls, it was also discovered that their shape varies depending on whether the pressure was applied between the forehead and the upper or lower part of the occiput (i.e., back of the skull). Hence, some had “normally arched foreheads but were flat behind, others were flattened at both front and back, and a few were asymmetrical because of uneven pressure.”

13. You Could Judge How Brave a Man Was by the Color of His Clothes

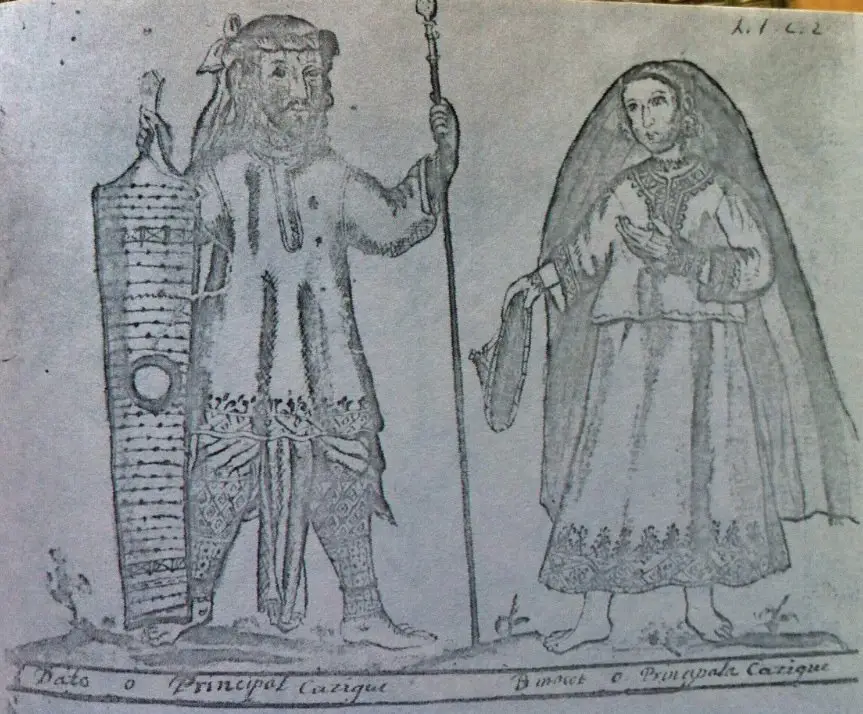

Clothing in the pre-colonial Philippines reflected one’s social standing and, in the case of men, how many enemies they had killed.

In the Visayas, for example, basic clothing included bahag (G-string) for men and malong (tube skirt) for women. The material used to make these clothes could indicate the wearer’s social status, with the abaca being the most valued textile reserved for the elites.

READ: The Controversial Origin of Philippines’ National Costume

The Visayan bahag was slightly larger than those worn by present-day inhabitants of Zambales, Cordillera, and the Cagayan Valley. They usually had natural colors, but warriors who personally killed an enemy could wear red bahag.

The same rule applied to the male headdress called pudong. Red was and still is the symbol of bravery, which explains why the most prolific warriors at that time proudly wore red bahag and pudong.

Historian William Henry Scott writes:

“A red ‘pudong’ was called ‘magalong’, and was the insignia of braves who had killed an enemy. The most prestigious kind of ‘pudong,’ limited to the most valiant, was, like their G-strings, made of ‘pinayusan,’ a gauze-thin abaca of fibers selected for their whiteness, tie-dyed a deep scarlet in patterns as fine as embroidery, and burnished to a silky sheen. Such pudong were lengthened with each additional feat of valor: real heroes therefore let one end hang loose with affected carelessness.”

14. Human Sacrifice Was a Bloody, Fascinating Mess

It’s not easy to be a slave in the ancient Philippines. When a warrior died, a slave was traditionally tied and buried beneath his body. If one was killed violently or if someone from the ruling class died (say, a datu), human sacrifices were almost always required.

Father Juan de Plasencia, an early missionary who authored “Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos” in 1589, provided us with a vivid portrait of an ancient burial:

“Before interring him (the chief), they mourned him for four days; and afterward laid him on a boat which serve as a coffin or bier…..If the deceased had been a warrior, a living slave was tied beneath his body until in this wretched way he died.”

Sometimes, as a last resort, an alipin was sacrificed in the hope that the ancestor spirits would take the slave instead of the dying datu. The slave could be an atubang or a personal attendant who had accompanied the datu all his life. The prize of his loyalty was often to die in the same manner as his master. So, if the datu died of drowning, the slave would also be killed by drowning. This is because of onong or the belief that those who belonged to the departed must suffer the same fate.

Related Article: Rare ritual burial may reveal cannibalistic ancestry.

Slaves from foreign lands could also be sacrificed. An itatanun expedition had the intention of taking captives from other communities. After being intoxicated, these captives would then be killed in the most brutal ways. Pioneer missionary Martin de Rada reported one case in Butuan wherein the slave was bound to a cross before being tortured by bamboo spikes, hit with a spear, and finally thrown into the river.

They believed that the dying datu was being attacked by the spirits of men he once defeated, and the only way to satisfy the ancestors was to kill a slave.

15. It Was Considered a Disgrace for a Woman To Have Many Children

There was no “family planning” in the pre-colonial Philippines. Everything they did was based on existing customs and beliefs, one of which was that having many children was undesirable and even a disgrace.

Such was their fear of having more children that pregnant women were prohibited from eating kambal na saging or similar food. They believed eating it would cause them to give birth to twins, which greatly insulted them.

Almost everyone also practiced abortion. The Boxer Codex reported that it was done with the help of female abortionists who used massage, herbal medicines, and even a stick to get the baby out of the womb.

READ: 10 Shocking Old-Timey Practices Filipinos Still Do Today

For others, having multiple children made them feel like pigs, so pregnant women with their second or third child would resort to abortion to get rid of their pregnancy. Poverty was another reason, as reported by Miguel de Loarca: “….when the property is to be divided among all the children, they will all be poor, and that it is better to have one child and leave him wealthy.”

According to historian William Henry Scott, the Visayans also had a custom of abandoning babies with debilitating defects, which made many observers conclude that “Visayans were never born blind or crippled.”

16. Celebrating a Girl’s First Menstruation, Pre-Colonial Style

Although menarche (first menstruation) is memorable for many women today, it rarely becomes a cause for celebration. In the precolonial era, however, this transition was seen as a crucial period in womanhood, so much so that all girls were required to go through an elaborate rite of passage.

The said ceremony was known as “dating” among ancient Tagalogs. It was usually held with the help of a catalonan (babaylan), the go-to priestess-cum-doctor at that time. During the ritual, the girl having her first period was secluded, covered, and blindfolded.

Isolation usually lasted four days if the woman was a commoner, while those belonging to the principal class had to go through this process for as long as a month and twenty days!

The Boxer Codex explains that our ancestors blindfolded the girl so she wouldn’t see anything dishonest and prevent her from growing up a “bad woman.” The mantles covering her, on the other hand, shielded her from wind blows, which they believed could lead to insanity.

The girl was prohibited from eating anything apart from two eggs or four mouthfuls of rice–morning and night, for four straight days. As if that’s not enough, the girl was also not allowed to talk to anybody for fear of becoming talkative. All of these, while her friends and relatives feasted and celebrated.

Also Read: 35 Outrageous Filipino Superstitions You Didn’t Know Existed

Each morning throughout the ceremony, the blindfolded girl was led to the river for her ritual bath. Her feet couldn’t touch the ground, so a catalonan or a male helper assisted her. The girl would be either led to the river through an “elevated walkway of planks” or carried by a male helper on his shoulder.

After immersing eight times in the water, the girl was carried back home where she would be rubbed with traditional male scents like civet or musk. Father Placensia, who witnessed the ritual, discovered later that the natives did this “in order that the girl might bear children, and have fortune in finding a husband to their taste, who would not leave them widows in their youth.”

17. Social Classes Were Not As Permanent as We Thought

When the ancient Filipinos started trading with outsiders, the economy also started to improve. This was when social classes emerged, and life suddenly became unfair.

As you may recall from the HEKASI subject that bored you as a kid, there existed four classes of pre-colonial Filipinos: There was the ruling datu class; the wealthy warrior class called maharlika; the timawa or freemen; and the most ‘unfortunate’ of them all–the alipin or uripon class.

Also Read: 11 Things From Philippine History Everyone Pictures Incorrectly

The alipin was divided into two sub-classes: the namamahay or those who owned their houses and only served their masters on an as-needed basis; and the saguiguilid who didn’t own a thing nor enjoyed any social privileges.

You might think being born a slave then was tantamount to being doomed for life. However, that’s not the case, as there were reports of those who moved up or down the pre-colonial social ladder.

In the case of the alipin, he could improve his social status by marriage. For example, as recorded by Father Plasencia, “if the maharlikas had children by their slaves, the children and their mothers became free.” Of course, this thing didn’t happen all the time, neither was it applicable to all social classes.

An alipin could also buy his freedom from his master if he were lucky enough to obtain gold through “war, by the grade of goldsmith, or otherwise.” However, note that inter-class mobility could only happen one step at a time. In other words, an alipin could never bypass other classes to become a datu overnight, and vice versa.

Other classes could also be demoted to the slave class for various reasons. Save for the datu or chiefs, anyone who committed a crime and failed to pay the fine would become a slave.

As for the datu, he could end up a low-ranked individual either because of poor leadership, which would prompt his followers to abandon him, or through an inter-barangay war, during which the captured and defeated datu, as well as his family, would lose some of their social privileges.

18. Courtship Was a Long, Arduous, and Expensive Process

Paninilbihan, or the custom requiring the guy to work for the girl’s family before marriage, was already prevalent during the pre-colonial period in the Philippines. From chopping wood to fetching water, the soon-to-be-groom would do everything to win his girl’s hand.

READ: The bizarre, painful sexual practices of early Filipinos

It often took months or even years before the parents were finally convinced that he was the right man for their daughter. And even at that point, the courtship wasn’t over yet.

The man was required to give bigay-kaya, or a dowry in the form of land, gold, or dependents. Of course, he needed the help of his parents to raise the required amount. Spanish chronicler Father Plasencia reported that a bigger dowry was usually given to a favored son, especially if he was about to tie the knot with the chief’s daughter. In the case of the Visayans, this dowry was usually given to the father-in-law, who would not entrust it to the couple until they had children.

Also Read: A Photo Of Ifugaos in Wedding Dress (1900)

In other areas of the country, the dowry was just the beginning. According to historian Teodoro Agoncillo, there was also the panghimuyat or the payment for the “mother’s nocturnal efforts in rearing the girl to womanhood”; the bigay-suso or payment for the girl’s wet nurse (if there’s any) who breastfed her when she’s still a baby; and the himaraw or the “reimbursement for the amount spent in feeding the girl during her infancy.”

As if that’s not enough to make the would-be groom go bankrupt, there was also the sambon among the Zambals which was a “bribe'” given to the girl’s relatives. Fortunately, through a custom called pamumulungan or pamamalae, the groom’s parents had the chance to meet the in-laws, haggle all they could, and make the final arrangements before the marriage.

References

Agoncillo, T. (1990). History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc.

Burton, R. (1919). Ifugao Law. American Archaeology And Ethnology, 15(1).

Carpio, A. (2014). Historical Facts, Historical Lies, And Historical Rights In The West Philippine Sea(1st ed., pp. 8-9).

Geremia-Lachica, M. (1996). Panay’s Babaylan: The Male Takeover. Review Of Women’s Studies, 6(1), 54-58.

Jocano, F. (1998). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage. Punlad Research House.

Junker, L. (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. University of Hawaii Press.

Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms. (2015). Asia Society. Retrieved 8 April 2016

Remoto, D. (2002). Happy and gay. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 9 April 2016

Scott, W. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press.

Vega, P. (2011). The World of Amaya: Unleashing the Karakoa. GMA News Online. Retrieved 8 April 2016

FilipiKnow

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net