30 Things You Didn’t Know About University of the Philippines (Part II)

The University of the Philippines is where future Filipino leaders and icons are born. From presidents Manuel Roxas and Ferdinand Marcos to local trendsetters in music like Eraserheads and Up Dharma Down, there’s no doubt that U.P. has contributed a lot in every field imaginable.

As a tribute to its commitment to shaping the minds of future Filipino trailblazers, here are other interesting facts you might not know about U.P.

Featured image courtesy of Mykee Alvero via Flickr.

Table of Contents

- 21. The first classes in UPLB were held in tents

- 22. U.P. used to have a yearbook called the Philippinensian

- 23. The model for the original Oblation was also the sculptor of the Oblation replica in UP Baguio

- 24. The UP Visayas-Iloilo City Campus Main Building used to be a city hall and WWII garrison

- 25. Krus na Ligas in UP Diliman used to be the meeting place of Andres Bonifacio and the Katipuneros

- 26. UP Cebu closed not just once, but twice

- 27. The UP Hayride and the first UP frat member to be killed in a rumble

- 28. A UP professor was fired in 1922 for criticizing a UP president

- 29. The highest grade achiever in UP’s history was also one of the country’s first Filipino actuaries

- 30. The first blind student who passed the first ever Brailled UPCAT

- Also Read: 30 Things You Didn’t Know About University of the Philippines (Part I)

- References

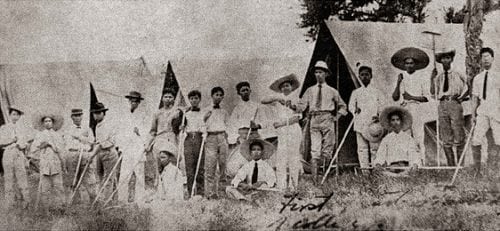

21. The first classes in UPLB were held in tents

Technically, it was in the house of American teacher Edgar M. Ledyard where the first class of the College of Agriculture was held on June 11, 1909 with 12 students . However, the makeshift classroom only lasted for three days.

From June 14 until the first college building was built four months later, tents borrowed from the Bureau of Education served as temporary classrooms for UPLB’s first batch of students. Led by Dean Edwin Copeland, the students and faculty members set up the tents in the northwestern part of Camp Eldridge (now the BPI-Los Baños Botanical Garden).

Classes were held in tents every morning, with students bringing their own stools and using their own thighs as their desks. Afternoons were usually spent hiking to the College “farm” which was four kilometers away.

UPLB traces its origins to 1908 when Dr. David Barrows of the Bureau of Education commissioned Dr. Edwin Copeland, then Instructor of Botany in the Philippine Normal School, to develop a school of agriculture. From a list of possible sites, Copeland picked Los Baños because “of its relative accessibility to attract more students, and its suitability for an insular agricultural experiment station.”

After the site was chosen, Copeland spent over a year negotiating with several “kaingeros” and other claimants to purchase a land at the foot of Mount Makiling. With the help of then Laguna Governor Juan Cailles, Copeland was able to negotiate the purchase of 72.63 hectares, which was then approved by the Board of Regents.

Copeland was later appointed Dean and Professor of Plant Physiology, his primary tasks being the establishment of the College of Agriculture and recruitment of the pioneering teaching staff. As you can remember, U.P. started with three units: the College of Agriculture (which paved the way for the establishment of UPLB years later); the Escuela de Bellas Artes which was adopted by U.P. as its School of Fine Arts; and the Philippine Medical School, renamed as the College of Medicine and Surgery.

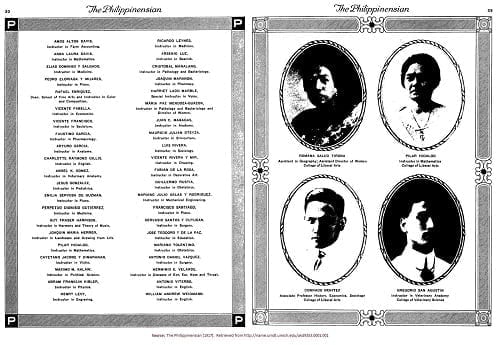

22. U.P. used to have a yearbook called the Philippinensian

First released in 1915, the Philippinensian was a yearbook of graduates which “chronicled the annual activities, events, and roster of graduating classes.”

Like the Cadena de Amor, however, the Philippinensian also met an untimely end as the university evolved. According to the book Icons and Institutions: Essays on the History of the University of the Philippines, 1952-2000 by Oscar Evangelista, the last issue of the now-defunct yearbook came out in 1971 with Bienvenido Noriega as the editor.

The death of the university annual was brought by different factors, among them the lack of interest to manage the publication and the expensive printing costs.

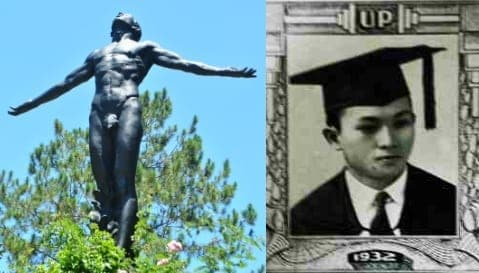

23. The model for the original Oblation was also the sculptor of the Oblation replica in UP Baguio

When UP Baguio was established in 1961, there was a suggestion among alumni members to have the original Oblation transferred to the Baguio campus. However, then UP President Vicente Sinco decided it was not a good idea after all, citing that the statue was too frail to even consider the transfer.

After Carlos P. Romulo took over the UP presidency, the idea of bringing the Oblation to UP Baguio came up once again, this time with the alumni members willing to sponsor the creation of a new statue. Romulo approved the idea and commissioned Anastacio Caedo to build the Oblation.

A graduate of UP School of Fine Arts, Batangueño sculptor Anastacio T. Caedo worked as Guillermo Tolentino’s assistant and, as previously mentioned, a model for the original Oblation statue.

Caedo’s finished product turned out a little bigger than the original, being the result of the mold made from the one in Diliman. Its base is also different: it is made of boulders which were originally used in a Safety Miner’s Week held in Burnham Park in 1962 and were donated to UP by the mining community.

Aside from the UP Baguio Oblation, Anastacio Caedo also made or designed various monuments for national heroes, among them the life-sized figures at the MacArthur Landing Memorial National Park in Leyte; the Juan Luna monument in Intramuros; and the Benigno Aquino monument in Makati.

Fondly called Mang Tasyo during his later years, Anastacio Caedo was also behind the trophies given by the Film Academy of the Philippines as well as some of the prosthetics used in Philippine movies during the 1950s.

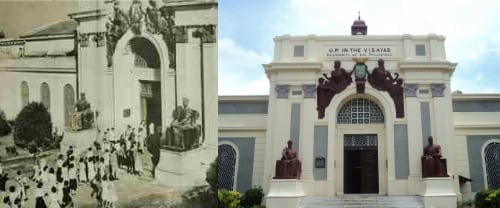

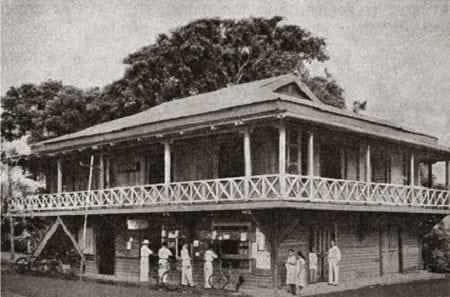

24. The UP Visayas-Iloilo City Campus Main Building used to be a city hall and WWII garrison

A constituent university of the UP system, the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV) is composed of three campuses: one in Iloilo City, another in Tacloban City, and the main campus in Miagao, Iloilo.

For someone who wants to explore UPV’s history, the main building at the Iloilo City campus is usually the starting point. Considered the oldest among surviving heritage structures, the building was designed by Filipino architect Juan Arellano and originally served as the city hall for Iloilo’s new chartered city in 1937. The building, completed in 1936, stands on the lot donated by Ilonggo philanthropist, Doña Juliana Melliza, in 1929.

The single-story building was built by Arellano in neo-classical style, with its facade stylized by Francesco Monti’s two seated bronze male sculptures symbolizing law and order. Inside the building are the Court Room and the Lozano Hall (or Session Hall), named after Congressman Cresenciano Lozano who authored the bill that granted Iloilo its status of a chartered city.

During the WWII (1943 to 1945), however, the Iloilo city hall was converted by the Japanese soldiers into a garrison. The post-war era saw the establishment of the UP Iloilo College (UPIC) and the formal donation of the city hall to the said school.

UPIC would later earn the status of a full-fledged college and was renamed UP College Iloilo (UPCI) in 1954. Finally, in 1980, through an executive order issued by President Ferdinand Marcos, the University of the Philippines in the Visayas (UPV) started to operate, with its first two colleges being the College of Fisheries (CF) and the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), formerly UP College Iloilo.

The city hall-turned-UPV main building was declared a National Historical Landmark by the NHCP in 2009.

25. Krus na Ligas in UP Diliman used to be the meeting place of Andres Bonifacio and the Katipuneros

Krus na Ligas is one of the eight barangays in U.P. Diliman. The area, known to UP students today for its several boarding houses, was among the large portion of land sold to UP by President Elpidio Quirino on April 2, 1949. However, historical records show that KNL already exists as early as the 19th century, predating the establishment of UP.

Formerly known as Gulod, the Krus na Ligas got its name from the ligas tree that was shaped like a cross when found in the area. According to the 2nd edition of the UP Diksiyonaryong Filipino, ligas has a scientific name of Semecarpus longifolius and is defined as a “mababang punongkahoy na malaman at makatas ang bunga na kahawig ng kasoy.”

It is said that one of the houses in front of the chapel in the old plaza used to be the meeting place of the Katipuneros. Back then, Gulod was a perfect hiding place because there were plenty of tall grasses in the area. In fact, on August 26, 1896, Gulod served as the meeting and resting place of Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, Guillermo Masangkay and other Katipuneros after engaging in a battle in Pasong Tamo, and before continuing to Pinaglabanan.

26. UP Cebu closed not just once, but twice

Since its inception in 1918, the University of the Philippines Cebu (known by different names throughout its evolution) had been threatened with closure several times. However, the educational institution officially closed only twice in history: first, during WWII; and second, throughout the 1950s.

On December 13, 1941, the then known Cebu Junior College closed due to the outbreak of WWII. For a time, its main building was used as an internment camp for American civilians and later converted into a prison by the Japanese troops. It was then briefly used by the United States Navy to house the General Engineering District Office after the Liberation. In late 1945, the campus was returned to the university and the classes resumed shortly thereafter.

Also Read:10 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Cebu

UPC closed once again in the 1950s, this time because of a controversy involving politicians. UP Cebu students, through editorial cartoons published in The Junior Collegian, criticized some of Cebu’s most powerful politicians and the acts of their armed goons during the presidential election in the late 1940s. The students’ fearlessness irked a Cebuano Senate President, resulting in the omission of the budget for UP Cebu by the Congress. Class 1950 was the last batch to graduate, while the rest of the students had no choice but to transfer to UP Diliman.

For 10 years, the school buildings were leased by the provincial government to the Jesuits, who then renamed the college into Berchman College. Fortunately, through the efforts of several alumni, UP Cebu reopened for the Graduate School. The high school and the undergraduate programs soon followed suit.

Once part of the UP in the Visayas (UPV), the University of the Philippines Cebu (UPC) was granted autonomy by the Board of Regents on September 24, 2010.

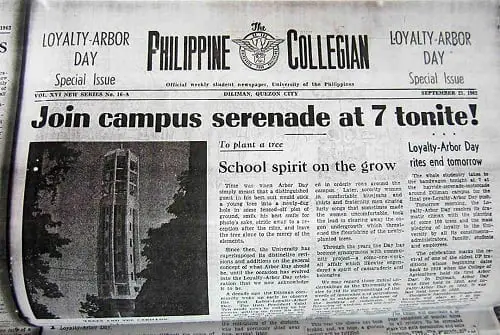

27. The UP Hayride and the first UP frat member to be killed in a rumble

Another lost tradition in U.P., the Hayride was an event wherein anyone may hitch a ride from open vehicles cushioned with hay. It usually coincided with the university’s celebration of Loyalty-Arbor Day. The first Hayride, according to the Philippine Collegian, was held on September 21, 1962.

During the joyous event, students and different organizations on a hayride would often sing or even outdo one another in making noises. The Hayride celebrations also involved a torch marathon wherein contestants would run around the campus while carrying a torch. They will then beat one another to become the first one to light the bonfire at the Union open court.

The death of a student named Rolando Perez during the Hayride celebration on September 22, 1969, saw the end of the tradition. Perez, a member of the Upsilon Sigma Phi, was killed during a clash with the Beta Sigma fraternity. Ironically, his older brother was a Beta Sigman.

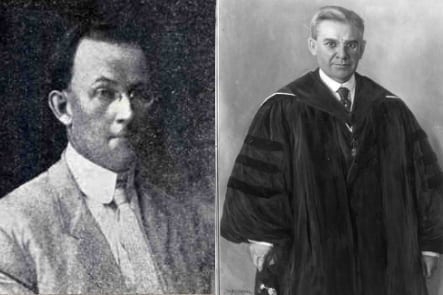

28. A UP professor was fired in 1922 for criticizing a UP president

Born in New York on February 22, 1878, Austin Craig was among the Americans who were qualified for the Philippine Civil Service in 1904. Soon, he became part of the Bureau of Education and taught in several schools in Manila such as the Philippine Normal School (now PNU), Philippine School of Arts and Trades (now TUP), and Manila High School (now Araullo).

Craig’s greatest accomplishment, however, was the writing of the books about Jose Rizal: The Story of Jose Rizal, followed by Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal, Philippine Patriot which were released in 1909 and 1911 respectively. The books became Craig’s ticket to enter the University of the Philippines as a Rizal research professor in 1912. Unfortunately, his stay in the university was cut short by a controversy that ultimately led to his dismissal in 1922.

In The University of the Philippines: the First Half Century published in the Diliman Review Golden Jubilee Supplement in 1958, Prof. Cristino Jamias details how Craig was dismissed on a charge of “conduct prejudicial to the interests of the university.” According to accounts, Prof. Craig had publicly criticized both UP President Guy Potter Benton, for his incompetence, and the members of the board of regents, including Dr. Rafael Palma who would succeed Benton as UP president upon the latter’s resignation.

Craig’s dismissal divided the UP community. In fact, four deans (namely, Jorge Bacobo, Maximo Kalaw, Francisco Benitez, and Herman Reynolds) cried foul at what could be described as the first controversy in UP involving academic freedom. In a petition, Bacobo specified the “five anomalies” in Craig’s dismissal, among them denying counsel to Craig, giving Craig only three days to prepare his defense, and the obvious fact that the board of regents acted both as the complainant and judge.

On the other hand, the official statement released by President Benton and Vice Governor Gillmore, president of the board of regents, suggests that the idea of “academic freedom” had its own limits:

“The regents, while they recognized that the principle of academic freedom is now firmly established in the world of scholarship, felt constrained to recognize that there is a plain line of demarcation always to be drawn between commendable freedom, which consists of fair comment and criticism of principles and policies, and reprehensible license, dealing in half truths and personalities.”

From UP, Prof. Craig transferred to the University of Manila where he would serve as a professor until 1927. He died in 1949 at the age of 70. A street in Sampaloc was named in his honor.

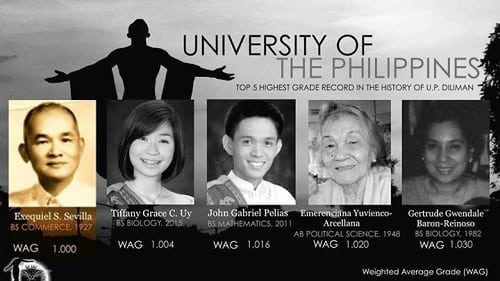

29. The highest grade achiever in UP’s history was also one of the country’s first Filipino actuaries

Although many have tried, Exequiel S. Sevilla’s perfect GWA of 1.0 is yet to be broken. Born on March 4, 1904, in Manila, Sevilla graduated summa cum laude with a Bachelor of Science in Commerce degree in 1927. The career he had after graduating from UP was just as stellar.

Sevilla was sent as a scholar to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where he completed his Master of Science degree in Actuarial Mathematics in 1929. He then trained for one year at the United States Life Insurance Company in New York City, before returning to Manila to work as an actuary for the Office of the Insurance Commissioner.

In case you’re wondering, an actuary, as defined by Purdue University, is “a business professional who analyzes the financial consequences of risk.” Actuaries usually apply mathematics, financial theory, and statistics in studying uncertain future events that are of great importance to insurance/pension programs. They are often hired by insurance companies, businesses, banks, hospitals, and the government.

Going back to Sevilla, he left government service in 1933 to help establish the National Life Insurance Co. where he would later serve first as an actuary, then general manager, and finally as its president and member of the board. In 1937, Sevilla was appointed by then President Manuel L. Quezon to the first board of directors of GSIS. He also shared his knowledge by teaching math at UP, University of the East, and Far Eastern University.

Sevilla also served as the president of the Philippine Statistical Association, the Philippine Association of Life Insurance Companies, Actuarial Society of the Philippines, and the Advanced Management Association of the Far East.

In 1979, Sevilla suffered a massive stroke that left him bedridden for several years. He died at his home in Manila on January 6, 1985. He was 80 years old.

30. The first blind student who passed the first ever Brailled UPCAT

In 2013, 15-year-old Paul Onel Dumlao became the first “totally blind” student to pass the University of the Philippines College Admission Test (UPCAT) given for the first time in Braille test booklet.

A senior student from the College of Immaculate Conception in Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, Dumlao graduated with honors despite suffering from visual impairment caused by retinopathy of prematurity. He was among the 13,028 students (out of 80,000) who successfully passed the highly-competitive entrance exam.

Although his initial choice was the European Languages program in Diliman, Dumlao was qualified to take the Bachelor of Arts in Social Sciences major in Economics program in UP Baguio.

In 2008, Special UPCAT was officially established to accommodate exam-takers with special needs, including those with visual or hearing impairments as well as students with autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and Tourette’s syndrome. Prior to 2013, UP Admissions had administered UPCAT to visually-impaired students either through dictation or by the use of handmade Braille exam that proved to be unsuccessful.

When Dumlao took the Special UPCAT, the test booklet was printed for the first time using a Braille embosser. For him, the Brailled UPCAT helped a lot in reading comprehension, but figures or numbers written in Braille were harder to visualize.

And since disabled students are given special consideration, Dumlao finished the Brailled UPCAT within 8 hours (twice the time limit given to regular test-takers). Mark Parcon, the other blind student who took the Special UPCAT with Dumlao, was unfortunately not included on the list of UPCAT passers.

Also Read: 30 Things You Didn’t Know About University of the Philippines (Part I)

References

Aguilar, C. (2008). Moving to Diliman. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 2 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/Z6LzMi

Alcazaren, P. (2012). Green and Marooned: The built and natural legacies of UP Diliman. UP Forum,13(6), 4.

Bernardo, F. (2007). Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB (pp. 11-15). Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association.

Boncan, C. (2012). Beginnings: University of the Philippines Manila. UP Forum, 13(6), 8.

Bonilla, C. (2009). Seeing double: UP Manila has 2 Oblations. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 22 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/o592xD

Cañete, R. (2009). From the Sacred to the Profane: The Oblation Ritualized. Humanities Diliman, 6(1-2).

Cañete, R. (2012). Campus of National Art: UP Diliman’s Heritage of Works by National Artists. UP Forum, 13(6), 19.

College of Engineering – University of the Philippines Diliman,. History – College of Engineering. Retrieved 26 June 2015, from http://coe.upd.edu.ph/history/

Dalisay, B. (2010). A pageant of presidents. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 2 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/DVNSl1

De la Cerna, M. (2010). History of the University of the Philippines Cebu. University of the Philippines Cebu Website. Retrieved 3 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/BBHGsE

Dinglasan, R. (2013). Two visually-impaired students try their luck in first Brailled UPCAT. GMA News Online. Retrieved 4 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/b2OQYP

Evangelista, O. (2008). Icons and Institutions: Essays on the History of the University of the Philippines, 1952-2000. UP Press.

Gonzalez, R. (2015). UP College of Engineering: Serving and Searching for Solutions. UP Forum,13(6), 12.

Halili-Jao, N. (2010). Hail the first female Pinoy doctors. philSTAR.com. Retrieved 22 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/bwhjf1

Harper, B. (2002). Exposicion Regional Filipina 1895. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. A9. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/FO6a0Q

Haskin, F. (1913). Is The Newest University: Higher Education in Philippines Is Making Natives Realize Power of Personal Efficiency. El Paso Herald. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/VZCJ0I

Hernandez, E. The Spanish Colonial Tradition in Philippine Visual Arts. National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved 22 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/PqQrr0

Hobart and William Smith Colleges Archives and Special Collections,. Murray Bartlett diary and transcript, 1918, 1973. Retrieved 1 July 2015, from https://goo.gl/j1r4mb

Inauguration of Guy Potter Benton, LL. D. as President of the University of the Philippines. (1922) (p. 4). Manila.

Inquirer.net,. (2013). Churches to visit in QC, Manila. Retrieved 26 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/ylMlPA

Jadloc, M. UP Traditions. University of the Philippines Diliman Website. Retrieved 27 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/Y0d48J

Luci, C. (2015). Bill filed to settle Krus na Ligas – UP land ownership. Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 3 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/6iA0FP

Madrid, R. (2012). UP Visayas: A Cultural Heritage. UP Forum, 13(6), 7.

Mateo, J. (2013). Visually impaired student is UPCAT passer. ABS-CBNNews.com. Retrieved 4 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/3CJRiw

Monsod, S. (2007). Tracking The Women’s Journey. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). Retrieved 2 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/iAzv2P

Ordoñez, E. (2008). A UP tale: The case of Austin Craig. The Manila Times, p. A4. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/Oqu92F

Ortiz, R. (2008). Facts and Trivia on the University of the Philippines. The Catalyst, (1), 7-11. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/4sLRPp

Peczon, J. Bartlett Watch (1st ed.). Retrieved from http://goo.gl/SU4Nsa

philSTAR.com,. (2008). NHI honors Batangueño artist Anastacio Caedo. Retrieved 2 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/haBd1w

Ramos, M. (2015). Reactivate public spaces in UP Diliman. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 3 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/SfSw6R

Richmond Times-Dispatch,. (1921). Philippine graduates to be garbed in white, p. 18. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/us7EcQ

Romualdo, A. (2011). Tales from UP Diliman: Fact or Fiction?. U.P. Newsletter, pp. 6-8. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/K9ppoN

Salvador-Amores, A. (2012). Sculpted Landmarks at UP Baguio. UP Forum, 13(6), 6. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/PBJpik

Scholars recall 1971 Diliman Commune. (2011). UP Newsletter, 29(4), 9.

Sevilla-Mendoza, A. (2011). Perfect 1: A record yet to be broken. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 4 July 2015, from http://goo.gl/t4CkEm

Taguiwalo, J. (2011). Who were the communards?. Philippine Collegian. Retrieved 27 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/1OqIN1

Tan, M. (2008). Three American presidents of UP. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 27 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/frvoJZ

The Ogden Standard-Examiner,. (1922). Island History Educator Fired, p. 2. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/F1SP8B

The Seattle Star,. (1920). Wilson Is Offered The Presidency of Philippines School, p. 12. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/Dq8LPy

The Washington Herald,. (1920). Filipinos Want Wilson There, p. 1. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/ZpDI3w

University of the Philippines System Website,. The University Seal. Retrieved 21 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/luw9c3

University of the Philippines System Website,. University History. Retrieved 20 June 2015, from http://goo.gl/nZZz0i

UPV Graduate Program Office Website,. The Oblation. Retrieved 21 June 2015, from https://goo.gl/Fe77Ku

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net