The Ancient Visayan Deities of Philippine Mythology

Unlike the Tagalogs, ancient Visayans didn’t have a creator god like Bathala who appeared out of nowhere and decided to create humanity. But what they lacked in “creator god” they made up for in plenty of origin myths. These stories explain how death, class and race differences, concubinage, war, and theft were introduced to the world.

They worshiped and offered prayers to a variety of invisible beings. These could either be a diwata (i.e. gods and goddesses) or the spirits of their ancestors called umalagad.

It is believed that the word diwata was derived from the Sanskrit devata which suggests Hindu influences to our pre-Spanish culture.

Also Read: The Ancient Tagalog Deities of Philippine Mythology

Our Visayan ancestors also believed in the afterlife, although theirs had no heaven or hell as we understand them today. The 17th century Augustinian priest Father Méntrida said that because these ancient Visayans had no knowledge of hell, “they call the Inferno, Solar (Sulad), and those who dwell in the Inferno, solanun.”

Most of these unfortunate souls were poor Visayans who either died without sufficient gold as pabaon or whose relatives couldn’t afford the required sacrifice to rescue them.

Couples who were reunited in the afterlife continued to do the same activities, although women could no longer conceive. The babies, on the other hand, did not have an afterlife. Instead, they were reincarnated for about nine times until in their final rebirth they were “buried in a coffin the size of a grain of rice.”

Also Read: The Ancient Mindanao Deities of Philippine Mythology

The Visayan underworld and the rest of the ancient domains were rife with interesting deities. Let’s have a rundown of some of these colorful characters who made the world less confusing for our ancestors.

1. Tungkung Langit and Alunsina.

The Sulod of Central Panay in Western Visayas believed that the universe was divided into three regions: Ibabawnun (upperworld), Pagtung-an (middleworld), and Idadalmunun (underworld).

Ibabawnun was further divided into two–a place ruled and inhabited by the male diwata, and the other by the female diwata.

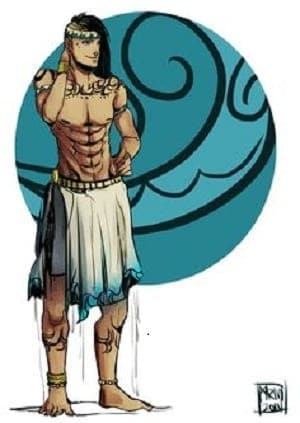

For the male section, a deity named Tungkung Langit (literally means “pillar of the skies”) was considered the supreme god or the highest-ranking deity. Alunsina, meanwhile, was the most powerful female diwata and the goddess of the eastern skies.

Tungkung Langit, just like Bathala, was assisted by several lesser divinities. Among them were Bangun-bangun, the “deity of universal time who regulated the cosmic movements”; Bahulangkug, the “diwata who changed seasons”; Ribun-linti (or Ribung-linti), the “god of lightning and thunderstorms”; Sumalongson, the “god of the river and seas”; Santonilyo, “deity of good graces”; and the most respected and feared of them all, Munsad Burulakaw.

Alunsina had her own assistants: Muropuro, the “goddess of the spring, rivers, and lakes”; Labing Daut, the “goddess-in-charge of rain-clouds”; and Tibang-Tibang, the goddess whose main responsibility was to maintain the balance in the world and make sure that day and night happened in succession.

Both Pagtung-an (middle world) and the Idadalmunun (underworld) were also ruled by deities. The underworld was under the jurisdiction of its highest ranking deity, Panlinugon, who also happened to be the god of earthquake.

Also Read: 0 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Cebu

The couple Paiburong and Bulawanon led other deities in keeping the middleworld in perfect order. They were helped by their five children, among them were Layang Sukla, goddess of beauty; Surangaun, god of the sea; and Tugang Tubig, god of rivers, streams, and lakes.

An origin myth from Panay suggests that Tungkung Langit and Alunsina, the chief gods of the upperworld, were actually married and settled down in heaven. The story, which was part of the old myths and legends compiled by anthropologist F. Landa Jocano in 1971, traced the origin of the world and celestial bodies.

After marrying Alunsina, Tungkung Langit worked non-stop to put an order in the confusing and still-shapeless world. He was described as a “loving, hard-working god,” while his wife a “lazy, jealous, and selfish goddess.”

READ: 12 Surprising Facts You Didn’t Know About Pre-Colonial Philippines

One day, as Tungkung Langit left their home in the skyworld to perform his duties, Alunsina ordered the breeze to follow and spy on her husband. When Tungkung Langit found out about it, a long argument ensued. The fight became so serious and hurtful that Alunsina decided to leave her husband, never to be seen again.

Several lonely months later, Tungkung Langit tried to find his wife everywhere, but to no avail. In desperation, he took Alunsina‘s jewels and spread them in the sky, hoping that somehow she would notice them and be compelled to return.

Sadly, Alunsina never bothered to come back. It is believed among the old folks of Panay that Alunsina‘s necklace became the stars, while her comb and crown became what we know today as the moon and sun, respectively.

They also think that the rain is actually the tears of Tungkung Langit falling from the sky. The thunders, on the other hand, could be the supreme god desperately calling for his beloved wife.

2. Kaptan and Magwayen.

Other parts of the ancient Visayas believed the world was divided into three regions: Kahilwayan or the skyworld; Kamariitan or the earth; and Kasakitan or the underworld.

Kaptan was the supreme god of these early Visayans. He lived in Kahilwayan and always passed through the Madyaas mountain in Panay every time he came down to earth.

Kaptan also had several minor deities under his supervision. The names of these lesser divinities are also the most difficult to remember.

Try it for yourself: Makliumsaiwan, the “lord of the plains and valleys”; Maklium-sa-bagidan, the “lord of fire”; Maklium-sa-tubig, the “lord of the sea”; Kasaray-sarayan-sa-silgan, the “lord of the streams”; Magdan-durunuum, the “lord of the hidden lakes”; Sarangan-sa-bagtiw, the “lord of storms”; and Suklang-Malayon, the “guardian of happy homes.”

READ: 10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines

According to an ancient origin myth recorded by Miguel de Loarca from the coastal people of Panay (possibly in Oton, Iloilo), Kaptan married a goddess named Magwayen and together they ruled the skyworld.

And just like what happened to Tungkung Langit and Alunsina, the two had an argument, ending up with Magwayen leaving her husband. To cope with his sorrow, Kaptan went to his garden called kabilyawan and there he planted a bamboo tube. As the plant grew by leaps and bounds, Kaptan thought of creating a man and a woman who could take care of the bamboo.

Before long, the bamboo split in half and from it came out the first man which Kaptan named Si Kalak (“the sturdy one”), and the first woman whom she christened Si Kabay. The two became the ancestors of humanity.

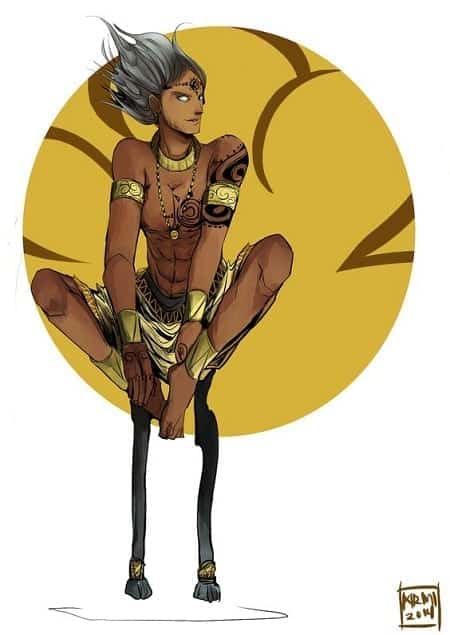

In other ancient stories, Magwayen was considered the goddess of the sea and death. Gregorio Zaide’s Philippine History and Civilization mentioned Maguayen as the “Visayan Acheron who ferried the souls of the dead from the land of the living to the other world.”

You can find the same information in William Henry Scott’s Baranggay. The ancient people of Panay knew Magwayen as the boatman who delivered the soul to the afterlife. Upon its arrival, the soul could either be accepted or rejected depending on whether he was decorated with sufficient gold jewelry. Those rejected would remain in Sulad or the ancient counterpart of Inferno unless his relatives offered enough sacrifices to save him.

3. Lihangin and Lidagat.

Another version of the Visayan origin myth suggests that Kaptan and Magwayen were not a couple. Instead, they were both guys, with Kaptan ruling over the skyworld and Magwayen lording over the water.

In the 1904 book, Philippine Folklore Stories by John Maurice Miller, Kaptan is said to be the father of Lihangin, the god of the wind, while Magwayen sired the goddess of the sea, Lidagat.

With the permission of their fathers, Lidagat and Lihangin got married and raised four kids: the strong Licalibutan who had a body made of rock; the always-happy Liadlaw (god of sun) who was covered with gold; the shy and weak Libulan (god of moon) who was made of copper; and the only daughter, Lisuga (god of stars), whose silver body always sparkled.

For a time, the family seemed to be happy and had no issues at all. However, everything changed when Lihangin and Lidagat died. Their eldest son, Licalibutan, became the victim of his own greed.

One day, he planned a surprise attack against the skyworld to hopefully seize its control from the supreme god Kaptan, his grandfather. Joining him were Liadlaw and Libulan who were too afraid of him to even think of backing out. Together, they went to the skyworld and blew up the gates protecting the kingdom.

Related Article: How Cebuano Fishermen Helped Defeat the Japanese in World War II

When Kaptan learned about the attack, he was enraged. The skygod sent three lightning bolts to his grandsons, which all melted instantly. Both Liadlaw and Libulan were reduced into a ball, while Licalibutan‘s rock-hard body broke into pieces, fell into the sea, and became what is known as land.

Lisuga, unaware of what was happening, also went to the skyworld to visit his grandfather. Kaptan, too blinded by his anger, struck the innocent Lisuga with lightning as well, breaking her into thousand pieces.

When he and Magwayen finally met, things started to sink in for Kaptan. He lost all his grandchildren, including the beautiful Lisuga who had nothing to do with the conspiracy at all.

The grief-stricken Kaptan, upon realizing he could no longer revive the four deities, decided to just provide their remains with an everlasting light. Hence, Liadlaw became the sun, Libulan became the moon, and Lisuga became what we know today as the stars.

As for the evil Licalibutan, Kaptan didn’t bother to give him light. He thought it was just fair to let him remain as it is–the land that would support the human race. Soon, Magwayen planted a seed on the said land and it didn’t take long before a bamboo tree started growing.

At this point, the story mirrors what happened in other Visayan origin myths: The tree split open and introduced us to the parents of the human race–the first man, Sicalac, and the first woman, Sicabay.

4. Varangao, Ynaguinid, and Macanduc.

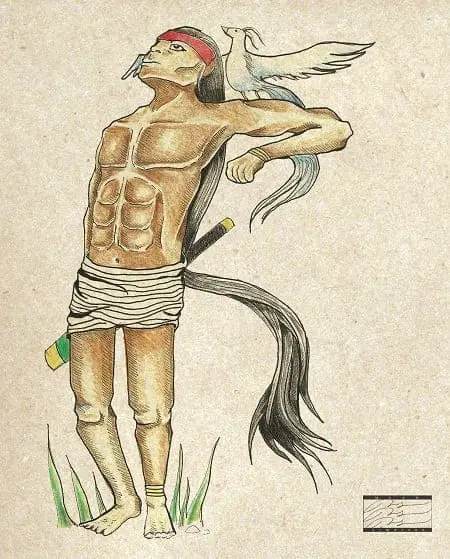

When a warrior died in a battle, the ancient Visayans believed that they traveled up the rainbow to the sky. In fact, in a Panay epic Labaw Donggon, the rainbow is said to be the blood of these fighters falling down to earth. These warriors also turn into gods once they reached the skyworld, the kingdom of Kaptan, and would guide any relatives who could avenge their deaths.

Among these warriors-turned-rainbows, a deity called Varangao was considered the most powerful. He became the god of the rainbow, and the natives prayed to him before going to war or plundering expeditions.

Aside from Varangao, two other names were mentioned by Miguel de Loarca as deities whom the indios offered prayers to for success in the battlefield. They were Ynaguinid and Macanduc, the Visayan gods of war whose dwelling places remain unknown.

5. Dalikmata and Bulalakaw.

While Kaptan and other major Visayan deities ruled over bigger, more spectacular domains, there were other diwatas invoked for specific human conditions. One example is the deity Makabusog (or Makabosog), who, as his name suggests, “moved men to gluttony.”

Another is the many-eyed goddess Dalikmata, whom our ancestors offered their prayers and sacrifices to whenever someone suffered an eye illness. They believed that once Dalikmata was pleased, the eye ailment would soon disappear.

The god Bulalakaw is the exact opposite. Unlike other healing deities, this supernatural being was said to be the giver of illnesses.

There are variations as to the origin and nature of this god, with some people of Panay worshiping him as their “bathala” who lived at the summit of Mt. Madyaas. Others believed Bulalakaw was a mythical bird with fiery feathers (another version says the fire is on its tail) who could magically cause illness to a person, and the only way to save his life was to appease the bird god with a ritual/offering.

6. The deities of the epic “Hinilawod.”

Hinilawod is an epic chanted by the Sulod people from the Panay island. It’s one of the longest epics in the world, and has two parts: the first one, containing 2,325 lines, is about the adventures of the demigod Labaw Donggon. The second cycle, meanwhile, focuses on Labaw Donggon‘s brother, Humadapnon, and has 53,000 lines.

Also Read: 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History

Labaw Donggon was the son of the goddess from the eastern skies, Alunsina, and her mortal husband, Buyung Paubari. Since he was half-god, Labaw Donggon was born with an extraordinary strength (think Hercules) and grew up quickly. He later fell in love and had multiple marriages with two beautiful women–Anggoy Ginbitinan, who lived at the mouth of the Halawod River, and Anggoy Doronoon, who was from the underworld.

But not content with his two wives, Labaw Donggon fell in love again, this time with Nagmalitung Yawa, the wife of Saragnayan, the deity responsible for directing the course of the sun. Other sources described Saragnayan as the “Keeper of Light,” while F. Landa Jocano, who recorded the epic himself, called him the “lord of the darkness.”

When Labaw Donggon asked for the hands of his wife, Saragnayan thought it was ridiculous to let go of his beloved without putting up a good fight. A battle ensued, culminating to Labaw Donggon submerging his opponent into the water for seven years.

But the giant Saragnayan survived every attack. Little did Labaw Donggon know, a wild boar in a place called Paling Bukid holds the life of Saragnayan, and the only way to kill him was to find and kill the pig as well.

Also Read: 12 Astonishing Philippine Artifacts You Didn’t Know You Could Find At The National Museum

In the end, Labaw Donggon was defeated and imprisoned below Saragnayan‘s kitchen. He was later rescued by Asu Mangga and Buyung Baranugun, his sons from the two previous marriages. The two used the pamlang or charms given by their mothers to defeat an army of diwatas and to kill the wild boar which served as the lifeline of Saragnayan. Everything went as planned, and Labaw Donggon escaped.

The first part of the epic ended with Labaw Donggon telling his brothers about Nagmalitung Yawa‘s two beautiful sisters–Burigadang Pada Sinaklang Bulawan, who was also the goddess of greed, and Lubaylubyok Hanginon Mahuyukhuyukon. The brothers then prepared for another journey, this time to win the hearts of the beautiful maidens.

7. Lalahon.

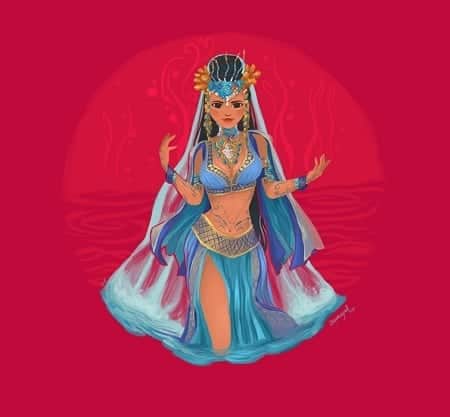

Contrary to popular belief, the ancient Visayan deity Lalahon was NOT the goddess of volcanoes. The name Lalahon (also called Laon, Lalon, or Lauon) first appeared in Miguel de Loarca’s Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas in 1582, where she was described as the goddess invoked by the natives for good harvest.

READ: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

It was said that she lived in Malaspina volcano (present-day Mt. Kanlaon) in Negros island. Now, this is where the confusion began. When the original Spanish passage by Loarca was translated for Blair and Robertsons’ The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 (Volume 5), the phrase “que hecha fuego” was mistranslated to “whence she hurls fire” instead of “which hurls fire,” leading others to assume that it was the goddess Lalahon, not the volcano where she lived, who spews out fire.

The truth, however, is that the natives worshiped her as the goddess of the good harvest. They believed that when displeased, Lalahon could send locusts to destroy their crops.

8. Makaptan.

As you may recall, the ancient Visayan world was divided into three regions, the first one being Kahilwayan (or skyworld) where the supreme god Kaptan lived. The other two were Kamariitan (earth) and Kasakitan (underworld).

Two chief deities were identified as the leader of Kamariitan: Sidapa, the goddess of death, and her husband, Makaptan, the god of sickness.

William Henry Scott’s Baranggay describes Makaptan as the “deity who killed the first man with a thunderbolt and visited disease and death on his descendants.” F. Landa Jocano, in his Outline of Philippine Mythology, added that the reason Makaptan brought diseases to the natives was that “he had not eaten anything of this food or drunk any pangasi (rice wine).” It pissed him off so much that he wanted the people to suffer as a consequence.

Also Read: Top 10 Lesser-Known Mythical Creatures in Philippine Folklore

As with other high-ranking deities, Makaptan and his wife had several deities who worked under them. These lesser divinities were supervised by a powerful god called Danapolay.

The underworld (Kasakitan), meanwhile, was ruled by Makaptan‘s brother, Sumpoy. When someone died, the soul would be transported to the infernal regions with the help of the boatman named Magyan (in other sources, his name is Magwayen), also a brother of Makaptan. Once there, Sumpoy would take over and bring the soul to Kanitu-nituhan where another deity called Sisiburanon was waiting.

If the relatives failed to offer sacrifices to save the soul of the departed, Sisiburanon would order the soul to be fed to two ferocious giants of the underworld–Simuran and Siguinarugan.

Note that during those times, all souls usually passed through the underworld before they could enter the skyworld. How quickly they would be transferred depended on whether their relatives gave sacrifices to a deity named Pandaque (or Pandaki), known as Sidapa‘s spokesman.

Also Read:

Part I: The Ancient Tagalog Deities of Philippine Mythology

Part III: The Ancient Mindanao Deities of Philippine Mythology

References

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net