Philippine Mythology Gods and Goddesses: An Ultimate Guide

Imagine yourself living in the pre-colonial Philippines.

No Christianity, Islam, or any of the modern-day religions. Everything you need to survive is literally in front of you–food, clothes, a roof over your head, you name it.

But while things around you seem to be in perfect order, a tidal wave of confusion starts forming in your mind.

You’re now questioning your very own existence. Questions you never knew you needed to answer are flooding your brain: Why is the sky blue? Where did we come from? Who controls everything? But with no religion to rely on, how can you possibly make sense of everything?

The answer, according to our ancestors, is Philippine mythology.

Nope, we won’t talk about the whitewashed deities you grew up watching in movies. While almost everybody is familiar with Zeus, Athena, Aphrodite, Eros, and other legendary gods of Greek mythology, it seems that we are all clueless about their Filipino counterparts. And that’s the reason why we’ve decided to write this article.

Philippine mythology is much more important than you think. It gave our ancestors a sense of direction and helped them explain everything–from the origin of mankind to the existence of diseases.

For them, it was not just a belief in invisible higher beings. Philippine mythology defined who they were and what they were supposed to do.

The late anthropologist H. Otley Beyer shared his observation:

“Among the Christianized peoples of the plains, the myths are preserved chiefly as folktales, but in the mountains, their recitation and preservation is a real and living part of the daily religious life of the people. Very few of these myths are written; the great majority of them are preserved by oral tradition only.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule in Philippine mythology. In other words, ancient Filipinos from every part of the country didn’t stick to a single version of the creation story nor give uniform names to their deities. As a result, Philippine mythology became so diverse that studying it now is like staring at a list of gazillion Pokémons.

It’s impossible to cover every deity in the chart (remember, this is a blog post, not a book). Still, we’ll try to feature the most interesting characters and make this as comprehensive as possible, FilipiKnow style.

Now, before we go straight to the most exciting part, it’s essential that we first go back to the basics.

Table of Contents

What Exactly Is Philippine Mythology?

Philippine mythology is a collection of stories and superstitions about magical beings, a.k.a. deities our ancestors believed controlled everything.

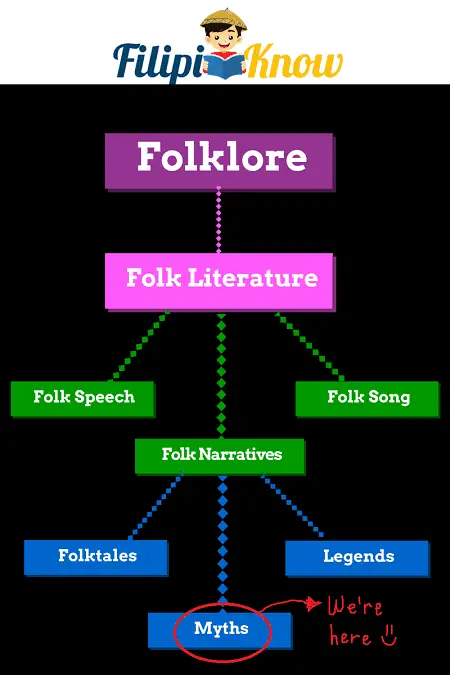

It’s part of the folklore, which covers all kinds of traditional knowledge embedded in our society: arts, folk literature, customs, beliefs, and games, among others.

If you’re going to examine the folklore family tree (see the chart below), you’ll see the folk literature branching out into three groups: folk speech (which includes the bugtong or riddles and salawikain or proverbs), folk songs, and the folk narratives.

Folk narratives are all about stories. They may be told in prose, verse, or both. They are further divided into three sub-categories: folktales or kuwentong bayan, legends or alamat, and myths.

The folktales are pure fiction, which you use to entertain bored kids. The legends and myths, meanwhile, are assumed to be true by the storyteller. It’s the timeline that sets them apart.

While legends happened in a much more recent period, myths are believed to have taken place in the “remote past,” meaning a period when the world as we know it today wasn’t fully formed yet.

According to the late Damiana L. Eugenio, the Mother of Philippine Folklore, myths “account for the origin of the world, of mankind, of death, or for characteristics of birds, animals, geographical features, and the phenomena of nature.”

The stories or adventures of deities fall under this sub-category. Deities are defined as supernatural beings with human characteristics.

These deities are either good or bad, each having a specific function. Renowned anthropologist F. Landa Jocano, the author of Outline of Philippine Mythology, explained it further:

“Some of these deities are always near; others are inhabitants of far-off realms of the Skyworld who take interest in human affairs only when they are invoked during proper ceremonies which compel them to come down to earth.”

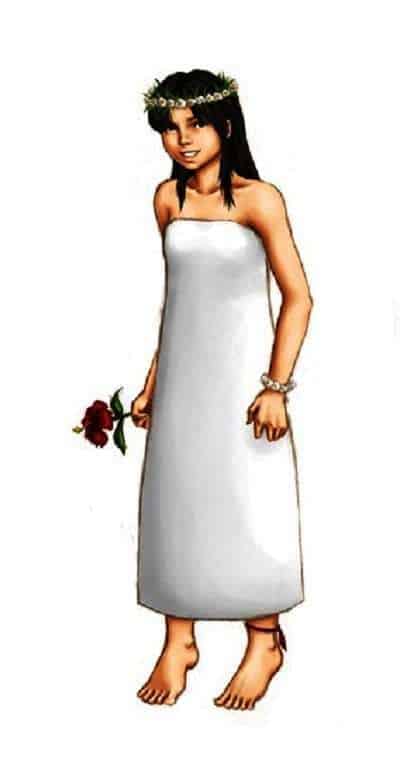

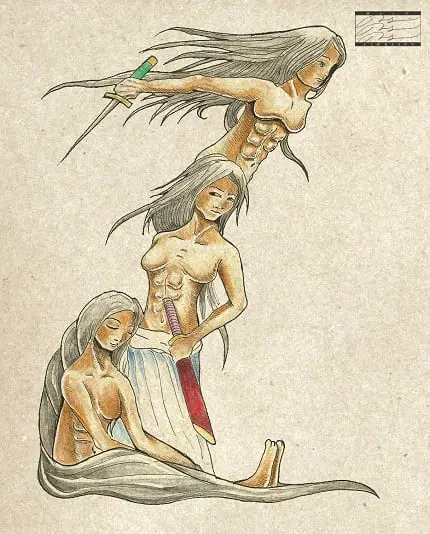

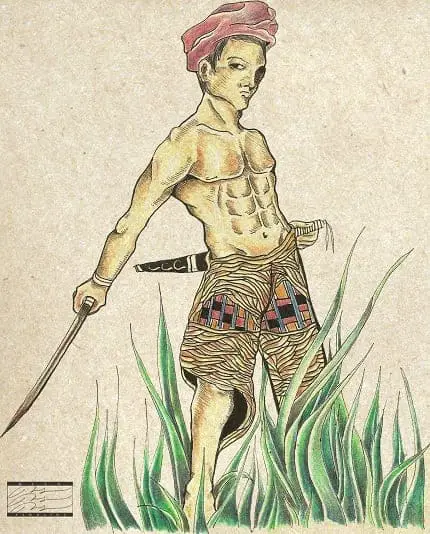

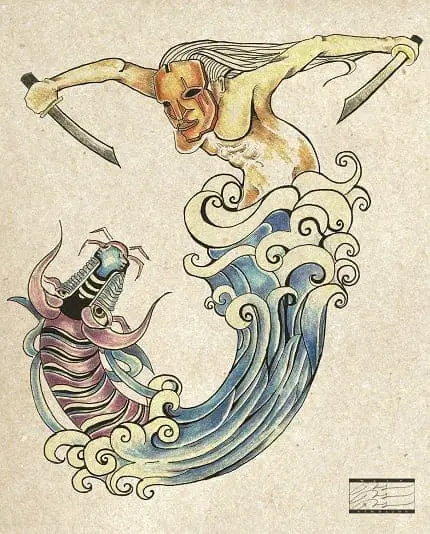

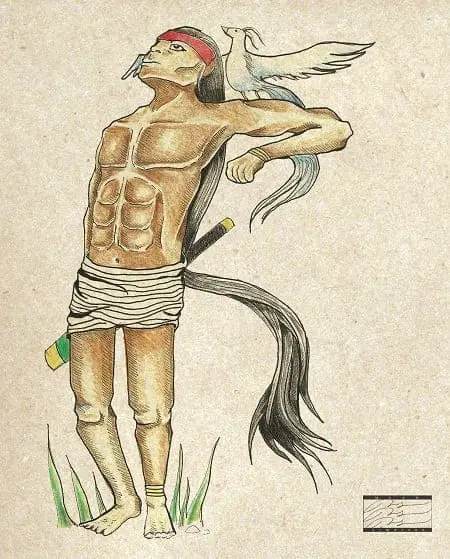

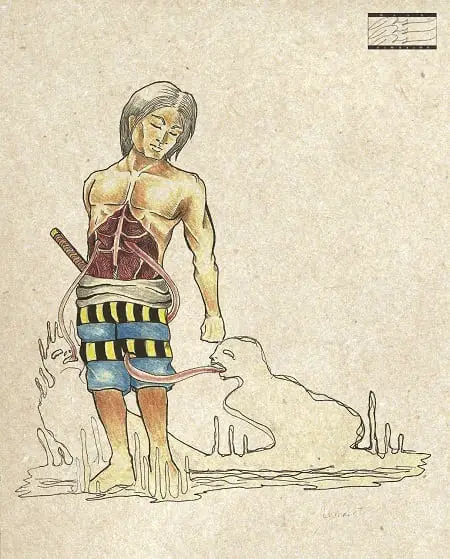

In this three-part series, you’ll learn more about these interesting deities from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. We’ll examine their stories, special powers, and other details that will tickle the curious child in you. Special thanks to the talented Pinoy graphic artists whose impressive works have helped bring these ancient deities back to life.

Note: All images presented in these articles are modern depictions of our ancient deities. History tells us that the colonizers burned representations of these gods and goddesses created by our ancestors. Therefore, the point of these illustrations is not to “Westernize” Philippine mythology but to make it more appealing and engaging to younger readers who ought to know more about their roots.

Part I: Luzon Divinities

Based on the early accounts of Spanish conquistador Miguel de Loarca, the ancient Tagalogs believed in one creator god. However, they didn’t have the power to communicate with him directly. An intercessor or “middleman” was required.

This go-between could either be the spirit of their dead relative or any of the lower-ranking deities. Ancient gods were usually worshiped in adobe carvings called likha, while the dead ancestors were revered by offering foods or gold adornments to wooden images known as anito.

Please take note that the early missionaries differed in how they defined anito. Father Pedro de San Buenaventura, for example, insisted that the word referred to the act of offering (“naga-anito”) and not the spirit itself (“pinagaanitohan”).

Aside from the deities and the souls of the departed, the ancient Tagalogs also venerated animals like crocodiles, believing that these wild beasts contained human souls. On the other hand, a tigmamanukan bird flying across someone’s path was considered an omen. Depending on the direction of its flight, this bird could foretell whether an expedition would end up a success or disaster.

1. Bathala

Also known as Abba, this highest-ranking deity was described as “may kapal sa lahat,” or the creator of everything. His origin is unknown, but his name suggests Hindu influences. According to William Henry Scott, Bathala was derived from the Sanskrit bhattara which means “noble lord.”

From his abode in the sky called Kawalhatian, this deity looks over mankind. He’s pleased when his people follow his rules, giving everything they need to the point of spoiling them (hence, the bahala na philosophy). But mind you, this powerful deity could also be cruel sometimes, sending lightning and thunder to those who sin against him.

Interesting fact: Other indigenous groups in Luzon also believed in a creator god, but they didn’t call him Bathala. For instance, the Bontoks and Kankanays of the Central Cordillera considered Lumawig the “creator of all things and the preserver of life.” This deity later sired two pretty daughters–Bugan, the goddess of romance, and Obban, the goddess of reproduction.

Those from Benguet honored Apo as their highest-ranking deity. Ifugaos, meanwhile, called their own Kabunian. The latter was believed to have inhabited the “fifth region of the universe,” and was assisted by other minor gods, among them Tayaban, the firefly-looking god of death; Gatui, the god of practical jokes who was also blamed for causing miscarriages among Ifugao mothers; Hidit, gods of the rituals responsible for giving punishments to those who broke taboos; and Bulol (or bulul), the famous Ifugao rice god worshiped in the form of small wooden statues resembling their ancestors.

Also Read: The Stunning Rice Terraces of Banaue and Antique

On the other hand, the early people of Zambales named their highest-ranking deity Malayari. Like the Bathala of the Tagalogs, this creator god rewarded his worshipers with good health and harvest and punished the unbelievers with disease and famine.

Lesser divinities also assisted Malayari in carrying out his tasks, among them Akasi, the god of health and sickness; Manglubar, the god of powerful living whose task was to “pacify angry hearts”; and the guardian angel Mangalabar, the god of good grace.

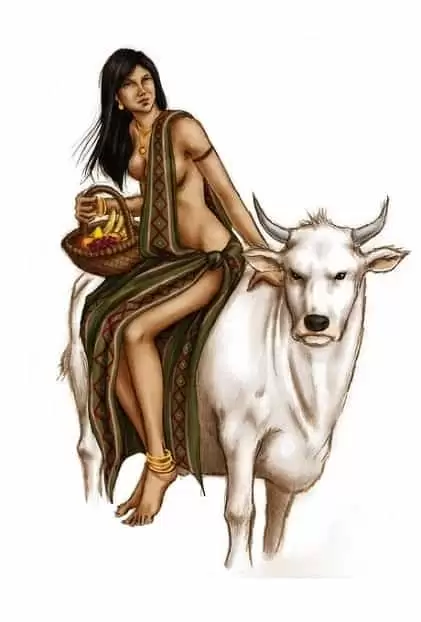

2. Idianale

If Bathala was the boss, the other lesser deities who lived with him in the sky were his assistants. Each of these lower-ranking gods and goddesses had specific responsibilities. One was Idianale (Idiyanale or Idianali in other sources), the goddess of labor and good deeds.

There are varying accounts as to what specific field Idianale was worshiped for. Historian Gregorio Zaide said that Idianale was the god of agriculture, while other sources suggest that she was the patron of animal husbandry, a branch of agriculture.

Idianale married Dumangan, the god of good harvest, and later gave birth to two more Tagalog deities: Dumakulem and Anitun Tabu.

3. Dumangan

Dumangan was the Tagalog sky god of good harvest, the husband of Idianale, and father to Dumakulem and Anitun Tabu.

In Zambales culture, Dumangan (or Dumagan) caused the rice to “yield better grains.” According to F. Landa Jocano, the early people of Zambales also believed Dumagan had three brothers who were just as powerful as him.

Also Read: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

Kalasakas hastened the ripening of the rice stalks, while Kalasokus was responsible for turning the grains yellow. Lastly, the deity Damulag protected the flowers of the rice plants from destructive hurricanes.

4. Anitun Tabu

Among ancient Tagalogs, Anitun Tabu was known as the “fickle-minded goddess of the wind and rain.” She’s one of the two children of Dumangan and Idianale.

In Zambales, this goddess was known as Aniton Tauo, one of the lesser deities assisting their chief god, Malayari. Legend has it that Aniton Tauo was once considered superior to other Zambales deities. She became so full of herself that Malayari reduced her rank as a punishment.

The Zambales people offered her the best kind of pinipig or pounded young rice grains during harvest season. Sacrifices that use these ingredients are known as mamiarag in their local dialect.

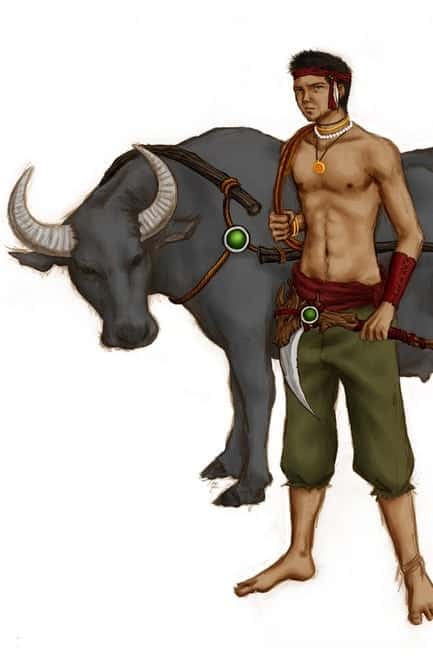

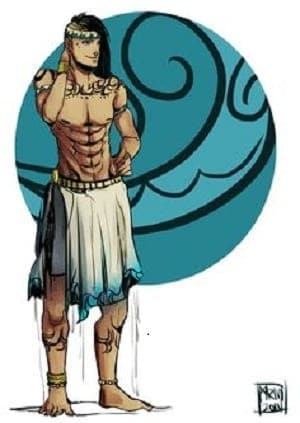

5. Dumakulem

Dumakulem was the son of Idianale and Dumangan, and brother of wind goddess Anitun Tabu. The ancient Tagalogs revered him as the guardian of the mountains. He is often depicted as a strong and skillful hunter.

This Tagalog sky god later tied the knot with another principal deity, Anagolay, known as the goddess of lost things. The marriage produced two children: Apolaki, the sun god, and Dian Masalanta, the goddess of lovers.

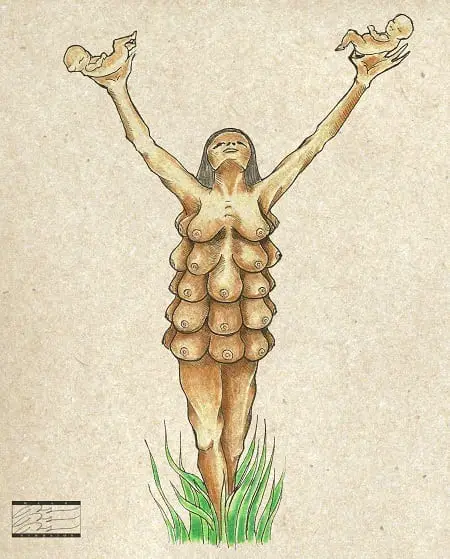

6. Ikapati/Lakapati

Probably one of the most intriguing deities of Philippine mythology, Ikapati (or Lakapati) was the Tagalog goddess of fertility. F. Landa Jocano described her as the “goddess of the cultivated land” and the “benevolent giver of food and prosperity.”

Some sources describe Lakapati as androgynous, hermaphrodite, and even a “transgender” god. In William Henry Scott’s “Baranggay,” Lakapati is described as a significant fertility deity represented by a “hermaphrodite image with both male and female parts.”

Also Read: The “Masuso” Pots of the National Museum

Before planting in a new field, the ancient Tagalogs usually offered sacrifices to Lakapati. In a 17th-century report by Franciscan missionary Father Pedro de San Buenaventura, it was said that a farmer paying homage to this fertility goddess would hold up a child before saying, “Lakapati pakanin mo yaring alipin mo; huwag mong gutumin” (Lakapati, feed this thy slave; let him not hunger).

Being the kindest among the lesser deities of Bathala, Lakapati was loved and respected by the people. She married the god of seasons, Mapulon, and became the mother of Anagolay, the goddess of lost things.

7. Mapulon

In Tagalog mythology, Mapulon was the god of seasons. F. Landa Jocano, in the book “Outline of Philippine Mythology,” described Mapulon as one of the lesser divinities assisting Bathala.

Not much is known about this deity, except that he married Ikapati/Lakapati, the fertility goddess, and sired Anagolay, the goddess of lost things.

8. Anagolay

Pre-colonial Tagalogs who were hopelessly looking for their missing stuff prayed to Anagolay, the goddess of lost things. She was the daughter of two major Tagalog deities–Ikapati and Mapulon.

When she reached the right age, she married the hunter Dumakulem. She gave birth to two more deities: Apolaki and Dian Masalanta, the ancient gods of the sun and lovers, respectively.

Interesting fact: In September of 2014, the Minor Planet Center (MPC), the international agency responsible for naming minor bodies in the solar system, officially gave the name (3757) Anagolay to an asteroid first discovered in 1982 by E. F. Helin at the Palomar Observatory.

Also Read: A Planet Named After A Filipino

The asteroid was named after the ancient Tagalog goddess of lost things. The name, submitted by Filipino student Mohammad Abqary Alon, bested more than a thousand entries in a contest held by the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC).

9. Apolaki

Arguably the Filipino counterpart of the Roman god Mars, Apolaki appeared in several ancient myths. The Tagalogs revered Apolaki as the sun god and patron of the warriors. He shares almost the same qualities with the Kapampangan sun god of war and death, Aring Sinukuan.

Early people of Pangasinan claimed that Apolaki talked to them. Back when blackened teeth were considered the standard of beauty, some natives told a friar that a disappointed Apolaki had scolded them for welcoming “foreigners with white teeth.”

In a book by William Henry Scott, the name of this deity is said to have originated from apo, which means “lord,” and laki, which means “male” or “virile.” Jocano’s Outline of Philippine Mythology details how Apolaki came to be: He was the son of Anagolay and Dumakulem, and the brother of Dian Masalanta, the goddess of lovers.

Also Read: 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History

In other stories, however, Apolaki was, in fact, the son of the supreme god of the ancient Tagalogs, Bathala. The book “Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales” by Maximo Ramos features how the sun became brighter than the moon. In the said myth, Bathala sired two children from a mortal woman. He named his son Apolaki and his daughter Mayari.

Both children had eyes so bright that they became the source of light for the rest of the world. When Bathala died, Apolaki and Mayari both wanted to succeed their father. A long, bloody argument ensued as neither wanted to relinquish the throne. The fight reached the boiling point when Apolaki hit Mayari‘s face with a wooden club, blinding her one eye.

Cooler heads prevailed, and both agreed to take turns in ruling the world. Apolaki now occupies the throne during the daytime while Mayari, the moon goddess, provides the “cool and gentle light” during nighttime, for she is blind in one eye.

10. Dian Masalanta

If the Greeks had Aphrodite, our Tagalog ancestors had Dian Masalanta. The patron goddess of lovers and childbirth, this deity was the sister of the sun god Apolaki to parents Anagolay and Dumakulem.

Also Read: The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in Philippine History

Sacrifices were offered to Dian Masalanta to ensure successful pregnancies. The same was done for other lesser deities who ruled specific domains, like Mankukutod, the protector of coconut palms who could cause accidents if the offering was not made. Haik, the sea god, was honored by sea travelers for a safe and prosperous voyage. At the same time, Uwinan Sana, the forest deity, was acknowledged so anyone who entered his “property” wouldn’t be punished for trespassing.

11. Amanikabli

Depending on your book, Amanikabli (Amanikable or Aman Ikabli in other sources) could be the ancient Tagalog patron of hunters or the god of the sea.

In the book Barangay by William Henry Scott and the 1936 Encyclopedia of the Philippines by Zoilo Galang, Amanikabli was identified as the Tagalog anito of hunters who rewarded his worshipers with good game.

On the other hand, the chief protector of the sea was Aman Sinaya (or Amanisaya in other references), who “gave his devotees a good catch.” In the same book by William Henry Scott, Aman Sinaya was described as the deity called upon by believers “when first wetting a net or fishhook.” He was also identified as the father of Sinaya, who invented the fishing gear.

Also Read: 10 Amazing Things We No Longer See In Pasig River

The works of anthropologist F. Landa Jocano beg to differ. According to his relatively more modern version, Amanikabli was one of the lesser deities assisting Bathala in Kawalhatian. He was described as “the husky, ill-tempered ruler of the sea,” whose hatred towards mankind started when a beautiful mortal woman, aptly named Maganda, rejected his love.

Since then, the sea god had made it his agenda to send “turbulent waves and horrible tempests every now and then to wreck boats and drown men.”

12-14. Mayari, Hana, and Tala

Once upon a time, Bathala fell in love with a mortal woman. She died after giving birth to three beautiful daughters. Of course, Bathala didn’t want anything wrong to happen to his girls, so he brought them to the sky to live with him.

Before long, these three demigods were given specific roles: Mayari, Hana (or Hanan in other references), and Tala became the Tagalog goddesses of the moon, morning, and star, respectively.

F. Landa Jocano’s Outline of Philippine Mythology flatteringly described the moon goddess as the “most beautiful divinity in the court of Bathala.” In other Luzon myths, however, the moon deity was anything but a beautiful goddess.

One Pangasinan myth tried to explain the origin of the sun, moon, and stars. The story starts with an all-powerful god called “Ama” giving a fiery palace to each of his two sons: Agueo (“sun”) and Bulan (“moon”). With their courts, these two gods would pass across the world daily to provide light to the people.

Agueo and Bulan are comparable to the Bible’s Cain and Abel. Between the two, Bulan was the naughty one. When he overheard a group of thieves wishing for darkness so they could steal and wreak havoc on mankind, Bulan was thrilled. He then asked his brother, Agueo, to quickly leave the earth so his evil friends could do their business. When Agueo refused, a heated argument took place.

Aware of everything that happened, Bathala was furious at Bulan. From his abode in the sky, he “seized an enormous rock and hurled it whistling through the air.” It hit Bulan‘s palace, breaking it into pieces. The flickering fragments became the stars. Bulan had since been banned from joining his brother in circling the world. He still lives in a fiery palace, but its dim light is enough to guide the thieves during nighttime.

Another Mayari story appeared in Maximo Ramos’ “Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales” and Dean S. Fansler’s “Filipino Popular Tales.” According to this myth from Pampanga, Mayari was the sister of the sun god, Apolaki, and both of them were gifted with bright eyes, which served as a light for the whole world.

The siblings argued about who deserved to take the throne when their father died. The fight ended with Mayari blinded in one eye after Apolaki hit her with a bamboo club.

Burdened by guilt, the sun god finally agreed to share the leadership with her sister. Apolaki soon became the “sun,” which provides warm light during the day, while Mayari (or the “moon”) rules every night with a cooler and dimmer light due to her blindness.

15-17. Lakanbakod, Lakandanum, and Lakambini

Not all deities of Philippine mythology lived in the sky with Bathala. Some co-existed with the ancient Tagalogs and were easily invoked during religious ceremonies headed by a catalonan.

Spanish lexicographers called these supernatural beings anito, Bathala‘s agents with specific functions. Three of the most interesting minor deities had names that rhyme together: Lakanbakod, Lakandanum, and Lakambini.

In William Henry Scott’s “Barangay,” Lakanbakod (Lakan Bakod or Lakambacod in other sources) was described as a deity who had “gilded genitals as long as a rice stalk.”

Lakanbakod was the “lord of fences,” a protector of crops powerful enough to keep animals out of farmlands. Hence, he was invoked and offered eels when fencing a plot of land.

Lakambini was just as fascinating. Although the name is almost synonymous with “muse” nowadays, it was not the case during the early times.

Up until the 19th century, lacanbini had been the name given to an anito whom Fray San Buenaventura described as “diyus-diyosang sumasakop siya sa mga sakit sa lalamunan.” In simple English, this minor deity was invoked by our ancestors to treat throat ailments.

Among the ancient Kapampangans, Lakandanum was known as the water god depicted as a serpent-like mermaid (naga). Before the Spaniards arrived, they often threw livestock into the river as a peace offering for Lakandanum. Failure to do so resulted in long periods of drought.

Every year during the dry season, the natives would sacrifice for the water god to give them rain. And when the rain started pouring, they would take it as a cue that Lakandanum had returned, and everyone would be in a festive mood.

The old Kapampangan new year, called Bayung Danum (“new water”), started as a celebration in honor of Lakandanum. When Christianity came into the picture, it was converted into the feast of St. John in Pampanga and the feast of St. Peter in other areas.

18-19. Galang Kaluluwa and Ulilang Kaluluwa

In some Tagalog creation myths, Bathala was not the only deity who lived in the universe before humanity was born. He shared the space with two other powerful gods: the serpent Ulilang Kaluluwa (“orphaned spirit”), who lived in the clouds, and the wandering god aptly named Galang Kaluluwa.

Ulilang Kaluluwa wanted the earth and the rest of the universe for himself. Therefore, he decided to fight when he learned of Bathala, who was eyeing the same stuff. After days of non-stop battle, Bathala became the last man standing. The lifeless body of Ulilang Kaluluwa was subsequently burned.

A few years later, Bathala and Galang Kaluluwa met. The two became friends, with Bathala inviting the latter to stay in his kingdom. But the life of Galang Kaluluwa was cut short by an illness. Upon his friend’s request, Bathala buried the body precisely where Ulilang Kaluluwa was previously burned.

Soon, a mysterious tree grew from the grave. Its fruit and wing-like leaves reminded Bathala of his departed friend, while the hard, unattractive trunk had the same qualities as the evil Ulilang Kaluluwa.

As it turned out, the tree is the “tree of life” we greatly value today- the coconut.

The importance of the coconut tree was so that when Bathala decided to create the first man and woman, he built a house for them using coconut trunks and leaves. As for their daily sustenance, the coconut’s juice and its succulent white meat proved to be nourishing.

Also Read: Philippine Fruits You Probably Don’t Know

It didn’t take long before they discovered more of the tree’s hidden gifts: Its leaves could turn into good mats or brooms, while the fiber could become sturdy ropes, among other things.

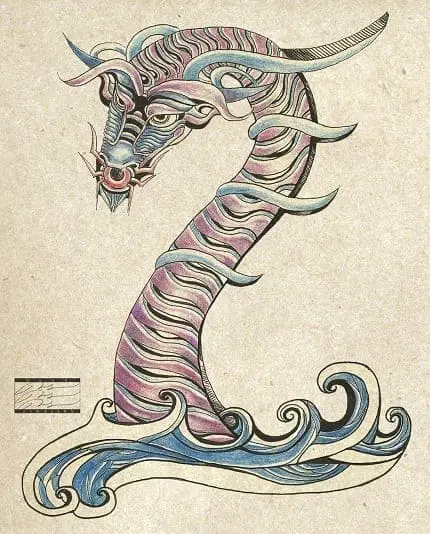

20-21. Haliya and the Bakunawa

Haliya is the moon goddess of Bicolano mythology who periodically comes down to earth to bathe in its waters.

Legend has it that the world used to be illuminated by seven moons. The gigantic sea serpent called bakunawa, a mythical creature found in the early Bicolano and Hiligaynon culture, devoured all but one of these moons.

In some myths, the remaining moon was saved after the gods came to the rescue and punished the sea monster. Another story suggests that Haliya was the name of the last moon standing, and she spared herself from being eaten by making noises using drums and gongs–sounds that the bakunawa found repulsive.

Pre-colonial Filipinos blamed the bakunawa for causing the eclipse. Its name, which means “bent serpent,” first appeared in a 1637 dictionary by Fr. Alonso de Mentrida. Bakunawa was deeply embedded in our ancient culture that by the time Fr. Ignacio Alcina penned his 1668 book Historias de las Islas e Indios de las Bisayas, the name of the sea serpent was already synonymous with the eclipse.

The Hiligaynon people of the Visayas believe that the bakunawa lives either in an area between the sky and the clouds or inside the bungalog, an underground passage “near the headwaters of big river systems.”

Believing that an eclipse was a bakunawa attempting to swallow the moon, ancient Visayans tried to ward off the monster by creating sounds. They did this by striking the floors of their houses or by beating cans, drums, and the like.

22. Sitan

In a way, our Tagalog ancestors already believed in the afterlife even before the colonizers introduced us to their Bible. One proof is the pre-colonial custom of burying the dead with a pabaon, which could be jewelry, food, or even slaves.

The modern-day heaven and hell also had ancient counterparts. Jocano said the early Tagalogs believed good guys would go to Maca, a place of “eternal peace and happiness.” On the other hand, the evil sinners were thrown into the “village of grief and affliction” called Kasanaan/Kasamaan.

The Kasanaan is a place of punishment ruled by Sitan, which shares striking similarities with Christianity’s ultimate villain, Satan. However, Jocano said that Sitan was most likely derived from the underworld’s Islamic ruler, Saitan (or Shaitan). This suggests that the Muslim religion already had a grip on our society way before the Spaniards arrived.

The vicious Sitan was also assisted by other lesser deities or mortal agents. First was Mangagaway, the wicked shapeshifter who wore a skull necklace and could kill or heal anyone with her magic wand. She could also prolong one’s death for weeks or months by binding a snake containing her potion around the person’s waist.

READ: Top 10 Lesser-Known Mythical Creatures in Philippine Folklore

Mansisilat was the homewrecker of Philippine mythology. As the goddess of broken homes, she accepted it as her mission to destroy relationships. She did this by disguising herself as an old beggar or healer who would enter the homes of unsuspecting couples. Using her charms, Mansisilat could magically turn husbands and wives against each other, ending in separation.

Equally frightening were Hukluban and Mankukulam.

William Henry Scott’s Baranggay described the former as “the most powerful kind of witch, able to kill or cause unconsciousness simply by greeting a person.” Jocano added that a Hukluban was also a terrific shapeshifter who could make anything happen–say, burn a house down–by simply uttering it.

The Mankukulam, on the other hand, often wandered around villages pretending to be a priest doctor. In Scott’s book, a mankukulam is described as a “witch who appears at night as if burning, setting fires that cannot be extinguished, or wallows in the filth under houses, whereupon some householder will sicken and die.”

Part II: Visayan Divinities

Unlike the Tagalogs, ancient Visayans didn’t have a creator god like Bathala, who appeared out of nowhere and decided to create humanity. But what they lacked in “creator god,” they made up for in plenty of origin myths. These stories explain how death, class and race differences, concubinage, war, and theft were introduced to the world.

They worshiped and offered prayers to a variety of invisible beings. These could either be diwata (i.e., gods and goddesses) or the spirits of their ancestors called umalagad.

It is believed that the word diwata was derived from the Sanskrit devata, which suggests Hindu influences to our pre-Spanish culture.

Our Visayan ancestors also believed in the afterlife, although theirs had no heaven or hell as we understand them today. The 17th-century Augustinian priest Father Méntrida said that because these ancient Visayans did not know hell, “they call the Inferno, Solar (Sulad), and those who dwell in the Inferno, solanun.”

Most of these unfortunate souls were poor Visayans who died without sufficient gold as pabaon or whose relatives couldn’t afford the required sacrifice to rescue them.

Couples reunited in the afterlife and continued to do the same activities, although women could no longer conceive. The babies, on the other hand, did not have an afterlife. Instead, they were reincarnated about nine times until, in their final rebirth, they were “buried in a coffin the size of a grain of rice.”

The Visayan underworld and other ancient domains were rife with interesting deities. Let’s run down some colorful characters who made the world less confusing for our ancestors.

1. Tungkung Langit and Alunsina

The Sulod of Central Panay in Western Visayas believed that the universe was divided into three regions: Ibabawnun (upper world), Pagtung-an (middle world), and Idadalmunun (underworld).

Ibabawnun was further divided into two: a place ruled and inhabited by the male diwata, and the other by the female diwata.

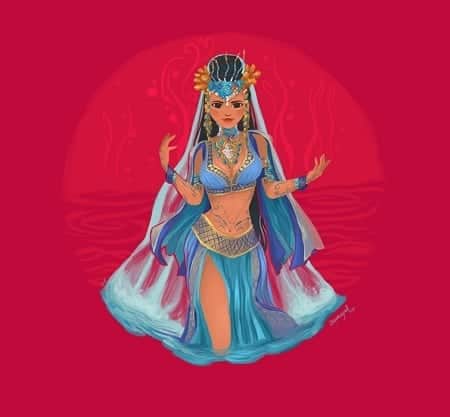

Tungkung Langit (literally means “pillar of the skies”) was considered the supreme god or the highest-ranking deity for the male section. Alunsina, meanwhile, was the most powerful female diwata and the goddess of the eastern skies.

Tungkung Langit, just like Bathala, was assisted by several lesser divinities. Among them were Bangun-bangun, the “deity of universal time who regulated the cosmic movements”; Bahulangkug, the “diwata who changed seasons”; Ribun-linti (or Ribung-linti), the “god of lightning and thunderstorms”; Sumalongson, the “god of the river and seas”; Santonilyo, “deity of good graces”; and the most respected and feared of them all, Munsad Burulakaw.

Alunsina had her own assistants: Muropuro, the “goddess of the spring, rivers, and lakes”; Labing Daut, the “goddess-in-charge of rain clouds”; and Tibang-Tibang, the goddess whose primary responsibility was to maintain the balance in the world and make sure that day and night happened in succession.

Deities also ruled Pagtung-an (middle world) and the Idadalmunun (underworld). The underworld was under the jurisdiction of its highest-ranking deity, Panlinugon, who also happened to be the god of earthquakes.

Also Read: 10 Amazing Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Cebu

The couple Paiburong and Bulawanon led other deities in keeping the middle world in perfect order. Their five children helped them; among them were Layang Sukla, goddess of beauty; Surangaun, god of the sea; and Tugang Tubig, god of rivers, streams, and lakes.

An origin myth from Panay suggests that Tungkung Langit and Alunsina, the chief gods of the upper world, were married and settled down in heaven. The story, part of the old myths and legends compiled by anthropologist F. Landa Jocano in 1971, traced the origin of the world and celestial bodies.

After marrying Alunsina, Tungkung Langit worked non-stop to put order in the confusing and still-shapeless world. He was described as a “loving, hard-working god,” while his wife was a “lazy, jealous, and selfish goddess.”

One day, as Tungkung Langit left their home in the sky world to perform his duties, Alunsina ordered the breeze to follow and spy on her husband. When Tungkung Langit found out about it, an extended argument ensued. The fight became so severe and hurtful that Alunsina decided to leave her husband, never to be seen again.

Several lonely months later, Tungkung Langit tried to find his wife everywhere, but to no avail. Desperate, he took Alunsina‘s jewels and spread them in the sky, hoping she would somehow notice them and be compelled to return.

Sadly, Alunsina never bothered to come back. It is believed among the old folks of Panay that Alunsina‘s necklace became the stars, while her comb and crown became what we know today as the moon and sun.

They also think that the rain is the tears of Tungkung Langit falling from the sky. Conversely, the thunders could be the supreme god desperately calling for his beloved wife.

2. Kaptan and Magwayen

Other parts of the ancient Visayas believed the world was divided into three regions: Kahilwayan, the sky world; Kamariitan, or the earth; and Kasakitan, or the underworld.

Kaptan was the supreme god of these early Visayans. He lived in Kahilwayan and always passed through the Madyaas mountain in Panay whenever he came down to earth.

Kaptan also had several minor deities under his supervision. The names of these lesser divinities are also the most difficult to remember.

Try it for yourself: Makliumsaiwan, the “lord of the plains and valleys”; Maklium-sa-bagidan, the “lord of fire”; Maklium-sa-tubig, the “lord of the sea”; Kasaray-sarayan-sa-silgan, the “lord of the streams”; Magdan-durunuum, the “lord of the hidden lakes”; Sarangan-sa-bagtiw, the “lord of storms”; and Suklang-Malayon, the “guardian of happy homes.”

According to an ancient origin myth recorded by Miguel de Loarca from the coastal people of Panay (possibly in Oton, Iloilo), Kaptan married a goddess named Magwayen, and together they ruled the sky world.

And just like what happened to Tungkung Langit and Alunsina, the two argued, ending up with Magwayen leaving her husband. To cope with his sorrow, Kaptan went to his garden called kabilyawan and there he planted a bamboo tube. As the plant grew by leaps and bounds, Kaptan thought of creating a man and a woman who could care for the bamboo.

Before long, the bamboo split in half and came out the first man Kaptan named Si Kalak (“the sturdy one”), and the first woman whom he christened Si Kabay. The two became the ancestors of humanity.

In other ancient stories, Magwayen was considered the goddess of the sea and death. Gregorio Zaide’s Philippine History and Civilization mentioned Maguayen as the “Visayan Acheron who ferried the souls of the dead from the land of the living to the other world.”

You can find the same information in William Henry Scott’s Baranggay. The ancient people of Panay knew Magwayen as the boatman who delivered the soul to the afterlife. Upon its arrival, the soul could be accepted or rejected depending on whether it was decorated with delicate gold jewelry. Those rejected would remain in Sulad or the ancient counterpart of Inferno unless his relatives offered enough sacrifices to save him.

3. Lihangin and Lidagat

Another version of the Visayan origin myth suggests that Kaptan and Magwayen were not a couple. Instead, they were both guys, with Kaptan ruling over the sky world and Magwayen lording over the water.

In the 1904 book, Philippine Folklore Stories by John Maurice Miller, Kaptan is said to be the father of Lihangin, the god of the wind, while Magwayen sired the goddess of the sea, Lidagat.

With the permission of their fathers, Lidagat and Lihangin got married and raised four kids: the strong Licalibutan, who had a body made of rock; the always-happy Liadlaw (god of sun), who was covered with gold; the shy and weak Libulan (god of moon) who was made of copper; and the only daughter, Lisuga (god of stars), whose silver body always sparkled.

For a time, the family seemed to be happy and had no issues at all. However, everything changed when Lihangin and Lidagat died. Their eldest son, Licalibutan, became the victim of his own greed.

One day, he planned a surprise attack against the sky world to hopefully seize its control from the supreme god Kaptan, his grandfather. Joining him were Liadlaw and Libulan, who were too afraid of him to even think of backing out. Together, they went to the sky world and blew up the gates protecting the kingdom.

Related Article: How Cebuano Fishermen Helped Defeat the Japanese in World War II

When Kaptan learned about the attack, he was enraged. The sky god sent three lightning bolts to his grandsons, which all melted instantly. Both Liadlaw and Libulan were reduced into a ball, while Licalibutan‘s rock-hard body broke into pieces, fell into the sea, and became what is known as land.

Lisuga, unaware of what was happening, also went to the sky world to visit his grandfather. Kaptan, too blinded by his anger, struck the innocent Lisuga with lightning, breaking her into thousand pieces.

When he and Magwayen finally met, things started to sink in for Kaptan. He lost all his grandchildren, including the beautiful Lisuga, who had nothing to do with the conspiracy.

Upon realizing he could no longer revive the four deities, the grief-stricken Kaptan decided to provide their remains with an everlasting light. Hence, Liadlaw became the sun, Libulan became the moon, and Lisuga became what we know today as the stars.

As for the evil Licalibutan, Kaptan didn’t bother to give him light. He thought it was just fair to let him remain as it is–the land that would support the human race. Soon, Magwayen planted a seed on the said land, and it didn’t take long before a bamboo tree started growing.

At this point, the story mirrors what happened in other Visayan origin myths: The tree split open and introduced us to the parents of the human race–the first man, Sicalac, and the first woman, Sicabay.

4. Varangao, Ynaguinid, and Macanduc

When a warrior died in a battle, the ancient Visayans believed they traveled up the rainbow to the sky. In fact, in a Panay epic Labaw Donggon, the rainbow is said to be the blood of these fighters falling to earth. These warriors also turned into gods once they reached the sky world, the kingdom of Kaptan, and would guide any relatives who could avenge their deaths.

Among these warriors-turned-rainbows, a deity called Varangao was considered the most powerful. He became the god of the rainbow, and the natives prayed to him before going to war or plundering expeditions.

Aside from Varangao, two other names were mentioned by Miguel de Loarca as deities whom the Indios offered prayers for success on the battlefield. They were Ynaguinid and Macanduc, the Visayan gods of war whose dwelling places remain unknown.

5. Dalikmata and Bulalakaw

While Kaptan and other major Visayan deities ruled over more significant, more spectacular domains, other diwatas were invoked for specific human conditions. One example is the deity Makabusog (or Makabosog), who, as his name suggests, “moved men to gluttony.”

Another is the many-eyed goddess Dalikmata, whom our ancestors offered prayers and sacrifices whenever someone suffered an eye illness. They believed that once Dalikmata was pleased, the eye ailment would soon disappear.

The god Bulalakaw is the exact opposite. Unlike other healing deities, this supernatural being was said to be the giver of illnesses.

There are variations in the origin and nature of this god, with some people of Panay worshiping him as their “bathala” who lived at the summit of Mt. Madyaas. Others believed Bulalakaw was a mythical bird with fiery feathers (another version says the fire is on its tail) that could magically cause illness in a person. The only way to save his life was to appease the bird god with a ritual/offering.

6. The Deities of the Epic “Hinilawod”

Hinilawod is an epic chanted by the Sulod people from Panay Island. It’s one of the longest epics in the world, and has two parts: the first one, containing 2,325 lines, is about the adventures of the demigod Labaw Donggon. The second cycle, meanwhile, focuses on Labaw Donggon‘s brother, Humadapnon, and has 53,000 lines.

Labaw Donggon was the son of the goddess from the eastern skies, Alunsina, and her mortal husband, Buyung Paubari. Since he was half-god, Labaw Donggon was born with extraordinary strength (think Hercules) and grew up quickly. He later fell in love and had multiple marriages with two beautiful women–Anggoy Ginbitinan, who lived at the mouth of the Halawod River, and Anggoy Doronoon, who was from the underworld.

But not content with his two wives, Labaw Donggon fell in love again, this time with Nagmalitung Yawa, the wife of Saragnayan, the deity responsible for directing the sun’s course. Other sources described Saragnayan as the “Keeper of Light,” while F. Landa Jocano, who recorded the epic himself, called him the “lord of the darkness.”

When Labaw Donggon asked for the hands of his wife, Saragnayan thought it was ridiculous to let go of his beloved without putting up a good fight. A battle ensued, culminating in Labaw Donggon submerging his opponent into the water for seven years.

But the giant Saragnayan survived every attack. Little did Labaw Donggon know a wild boar in a place called Paling Bukid held the life of Saragnayan, and the only way to kill him was to find and kill the pig.

Ultimately, Labaw Donggon was defeated and imprisoned below Saragnayan’s kitchen. He was later rescued by Asu Mangga and Buyung Baranugun, his sons from previous marriages. The two used the pamlang or charms given by their mothers to defeat an army of diwatas and to kill the wild boar, which served as the lifeline of Saragnayan. Everything went as planned, and Labaw Donggon escaped.

The first part of the epic ended with Labaw Donggon telling his brothers about Nagmalitung Yawa‘s two beautiful sisters–Burigadang Pada Sinaklang Bulawan, who was also the goddess of greed, and Lubaylubyok Hanginon Mahuyukhuyukon. The brothers then prepared for another journey, this time to win the hearts of the beautiful maidens.

7. Lalahon

Contrary to popular belief, the ancient Visayan deity Lalahon was NOT the goddess of volcanoes. The name Lalahon (also called Laon, Lalon, or Lauon) first appeared in Miguel de Loarca’s Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas in 1582, where she was described as the goddess invoked by the natives for a good harvest.

READ: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

It was said that she lived in Malaspina volcano (present-day Mt. Kanlaon) in Negros island. Now, this is where the confusion began. When the original Spanish passage by Loarca was translated for Blair and Robertsons’ The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 (Volume 5), the phrase “que hecha fuego” was mistranslated to “whence she hurls fire” instead of “which hurls fire,” leading others to assume that it was the goddess Lalahon, not the volcano where she lived, who spews out fire.

The truth, however, is that the natives worshiped her as the goddess of the good harvest. They believed that Lalahon could send locusts to destroy their crops when displeased.

8. Makaptan

As you may recall, the ancient Visayan world was divided into three regions, the first being Kahilwayan (or sky world), where the supreme god Kaptan lived. The other two were Kamariitan (earth) and Kasakitan (underworld).

Two chief deities were identified as the leader of Kamariitan: Sidapa, the goddess of death, and her husband, Makaptan, the god of sickness.

William Henry Scott’s Baranggay describes Makaptan as the “deity who killed the first man with a thunderbolt and visited disease and death on his descendants.” F. Landa Jocano, in his Outline of Philippine Mythology, added that the reason Makaptan brought diseases to the natives was that “he had not eaten anything of this food or drunk any pangasi (rice wine).” It pissed him off so much that he wanted the people to suffer.

As with other high-ranking deities, Makaptan and his wife had several deities who worked under them. These lesser divinities were supervised by a powerful god called Danapolay.

Meanwhile, the underworld (Kasakitan) was ruled by Makaptan‘s brother, Sumpoy. When someone died, the soul would be transported to the infernal regions with the help of the boatman named Magyan (in other sources, his name is Magwayen), also a brother of Makaptan. Once there, Sumpoy would take over and bring the soul to Kanitu-nituhan where another deity called Sisiburanon awaited.

If the relatives failed to offer sacrifices to save the departed’s soul, Sisiburanon would order the soul to be fed to two ferocious giants of the underworld–Simuran and Siguinarugan.

Note that during those times, all souls usually passed through the underworld before they could enter the sky world. How quickly they would be transferred depended on whether their relatives sacrificed to a deity named Pandaque (or Pandaki), known as Sidapa‘s spokesman.

Part III: Mindanao Deities

If you think the Tagalog and Visayan mythology is mind-blowing enough, wait until you see what Mindanao offers. Religion and culture in the south are unique because of the Muslim and Hindu-Javanese influences that shaped them.

As a result, how our Mindanaoan ancestors worshiped the spirits in the pre-colonial era combined their old beliefs and those of the foreigners they came in contact with.

The colorful and fascinating Mindanao mythology would have probably died with our ancestors were it not for the few dedicated people who took the risk to study them.

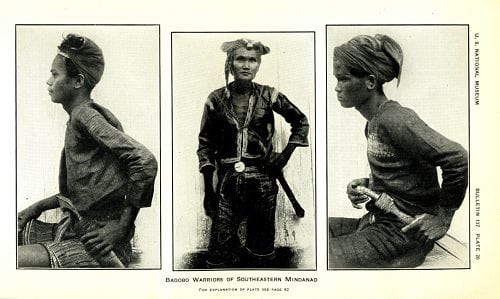

The first mention of the Bagobos was in a letter written by a missionary named Fr. Matteo Gisbert, S.J. However, at the dawn of the 20th century, two authors went the extra mile and lived with the Bagobo tribe. They immersed themselves in their culture and wrote all the data they collected in their books.

I’m talking about Laura Estelle Watson Benedict, an anthropologist, and Fay Cooper Cole, author of “The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao.”

Thanks to these researchers’ hard work, we now know how our Mindanaoan ancestors made sense of everything. Take, for instance, the Bagobos: they didn’t understand “birth” and “death” as we do today. For them, there was no real death because there was no country for the departed souls, nor did they believe in “birth,” as they assumed the god made the additional creatures and left them so they could raise the babies on their own.

The Mindanao mythology is as colorful as the many tribes that lived on the island. They include the Bagobo, Manobo, Bukidnon, Subanon, and Tiruray. Let’s jump right in and explore the magical world of ancient Mindanao.

1. Pamulak Manobo

Among the Bagobos of Mindanao, a supreme god called Pamulak Manobo was considered the creator of everything.

In Laura Watson Benedict’s “Bagobo Myths,” this diwata (a general term for deities) was also believed to be the creator of the first man and woman–Tuglay and Tuglibon. Another version suggests that the first humans were shaped out of corn meals and given life by Tuglay and Tuglibon, not Pamulak Manobo.

Going back to Benedict’s version of the story, Pamulak Manobo also created an eel (kasili) and a crab (kayumang). These two creatures are always together, and an earthquake occurs every time the crab bites the eel.

Pamulak Manobo was believed to be in control of other natural occurrences. When it rained, for example, the Bagobos believed it was the great god spitting or throwing water from heaven. On the other hand, the white clouds were actually the smoke from the fire produced by the other gods.

Also Read: Meet the Terrifying Moro Warriors and Heroes of WWII

Like his Luzon and Visayan counterparts, other lower-ranking deities also assisted this Bagobo god. Among them were Mandaragan and his wife Darago, the gods of war who lived inside Mt. Apo; Tigyama, the protector of families; and Tarabumo, the god of agriculture and whom a shrine called parobanian was built for.

There were also bad spirits working for Pamulak Manobo, including Buso, who fed on the flesh of the dead and was described as “huge beings with curly hair, big feet and long nails, small arms, and possessed two big, pointed front teeth.”

2. Tuglay and Tuglibon

Tuglay and Tuglibon are the most prominent figures in ancient Bagobo culture. In Jocano’s Oultine of Philippine Mythology, they are classified as assistants to Pamulak Manobo and were responsible for the births, marriages, language, and customs of the tribe.

In other sources, however, these two deities were either the world’s creator or co-creator of humanity. One of the Bagobo myths compiled by anthropologist Laura Estelle Watson Benedict shares similarities with Adam and Eve’s biblical story.

Also Read: 8 Real Filipina Queens and Princesses Too Awesome for Disney Movies

Tuglay and Tuglibon created the world in the myth, while an equally powerful yet unidentified god made the first man and woman. One day, a snake approached the first humans and offered them a fruit. The cunning reptile convinced them to eat the said fruit so they could “open their eyes,” only to find out later that eating it prevented them from seeing the god forever.

In yet another interesting version of the origin myth, Tuglibon (or Tuglibong in other sources) was pounding rice when she noticed the sky was too close to the ground and was interfering with her activity. She scolded the sky and asked it to move up higher. The latter did as he was told, which explains why the sky is where it is now.

As for the origins of their names, the second syllable in Tuglay (i.e., “lay” or “lai”) means “man” in Malay, while the “libon” in Tuglibon means “virgin.”

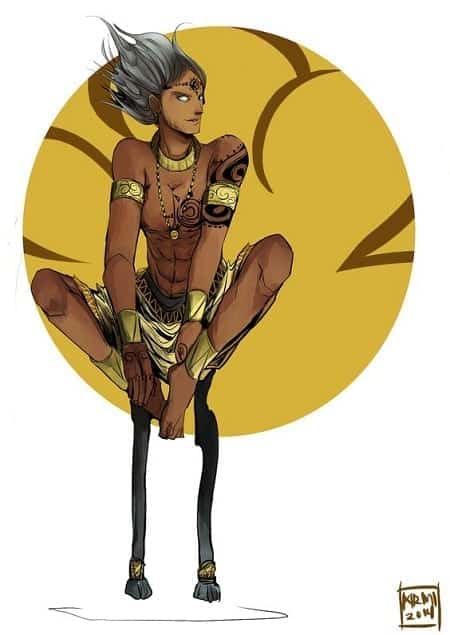

3. Mebuyan and Lumabat

According to one Bagobo and Manobo myth, there once lived two deities named Lumabat (god of the sky) and Mebuyan (goddess of the underworld). They were siblings but complete opposites of each other.

Lumabat was a terrific hunter who once brought along his dog to catch an elusive deer. The hunt took so long that he was already old and gray when he caught the animal. Still, he returned to his people, eager to show them his power. Lumabat even killed his father eight times, and each time the latter magically came back to life, he became younger and younger.

When it was time for Lumabat to go to heaven, he wanted his sister, Mebuyan, to join him. The latter refused, and they started fighting each other. The Bagobo mythology describes Mebuyan as an ugly deity who decided to go down below the earth, where she now rules a place called Banua Mebu’yan (Mebuyan’s town). Here, she welcomes the spirits of the dead Bagobos before they go straight to Gimokudon, the Bagobo equivalent of the underworld.

It is said that Mebuyan has many breasts because she nurses and takes care of all the baby spirits before they join their families in Gimokudon. Adult spirits also stop by Mebuyan’s town, specifically in the black river, where they wash their joints and heads.

The ritual bath, known as pamalugu, is done so that the spirits will not return to their earthly bodies and disrupt their journey to the underworld.

Note that the Manobo or Bagobo underworld, at least the one ruled by Mebuyan, has a relatively more positive connotation. It’s not a place where you can find a lake of fire and where the unbelievers are punished forever. In the book “Arakan, Where Rivers Speak of The Manobo’s Living Dreams” by Kaliwat Theatre Collective, Datu Mangadta Sugkawan gives us an interesting description of Mebuyan and her domain:

“Maibuyan (Mebuyan)….the diwata (deity) of the afterlife who takes care of all the souls before they receive Manama’s (Supreme Being) judgment…. Maibuyan’s entire domain is of pure gold on which the soul could clearly see its reflection. The souls there only talk about good and sensible things. If one starts to talk, everybody else listens. There is no need for food. Maibuyan’s domain in the underworld is where the soul lives a second life after its body–the physical twin–dies.”

Among the Ata-Manobo, a similar deity also existed. Rolando O. Bajo’s “The Ata-Manobo: At the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernization” introduces us to a god of the afterlife named Moibulan. This deity takes care of the spirits in a place at the bottom of the earth called Sumowow, where the souls can only experience peace and happiness as they await their final judgment.

4. Tagbusan

The Manobos also believed in a supreme god–Tagbusan. This highest-ranking deity “ruled over the destiny of both gods and men.” And just like others of his kind in Philippine mythology, Tagbusan was also helped by other lesser divinities.

Among those who assisted Tagbusan in his day-to-day responsibilities were Kakiadan, the goddess of rice; Taphagan, the goddess of harvest; Tagbanua, the rain god; Umouiui, god of clouds; Sugudun (or Sugujun), the god of hunters; Libtakan, god of sunrise and sunset; Yumud, god of water; Ibu, the queen or goddess of the underworld; and Apila, god of wrestling and sports.

There were also Manobo deities with evil intentions, like Tagabayau, the goddess who convinced people to engage in adultery or incest, and Agkui, a diwata who urged men to indulge in sexual excesses.

5. Magbabaya

Another essential deity from Mindanao is Magbabaya, considered by the Bukidnon as their highest-ranking deity. Other lesser divinities likewise assisted him:

Domalongdong, the deity of the Northwind; Ognaling, the deity of Southwind; Tagaloambung, the deity of Eastwind; and Magbaya, the divinity of the Westwind.

Other interesting deities of Bukidnon mythology are Ibabasag, patroness of pregnant women; Ipamahandi, goddess of the accident; and Tao-sa-sulup, god of material goods.

Among these gods and goddesses, a deity named Tigbas was the most respected by the Bukidnon, while the god of calamity, Busao, was the most feared and the last one they offered sacrifices to.

6. Other Mindanao Deities

Mindanao is composed of many tribes, and in each tribe, one can find plenty of deities and supernatural beings. I know it’s impossible to cover them all in one blog post but to live up to my promise of providing an “ultimate guide,” I’ll briefly mention some of them here.

The Tirurays believed that the first man and woman were created by a superhuman named Sualla (or Tullus-God), who lived in the sky.

The Gianges of Cotabato, meanwhile, prayed to two major deities: Tigianes, creator of the world, and Manama, her governor. They also worshiped Todlay and Todlibun (notice the similarity with the Bagobos’ Tuglay and Tuglibon), the gods of love and marriage, respectively.

Lastly, the Subanuns of upper Zamboanga were also guided by several deities, the most powerful of which was Diwata-sa-langit, the god of heaven. The other deities are Tagma-sa-dagat, lord of the sea; Tagma-sa-yuta, lord of the earth; Tagma-sa-mangga-bungud, lord of the woods; Tagmasa-uba, lord of the rivers; and Tagma-sa-langit, god and protector of the sick.

References

(1999). Philippine Quarterly Of Culture And Society, 27, 123.

Eugenio, D. (2007). Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology. University of the Philippines Press.

Fansler, D. (1921). Filipino Popular Tales: Collected and Edited with Comparative Notes. New York: The American Folklore Society.

Fores- Ganzon, G. & Mañeru, L. (1995). La Solidaridad, Volume 5 (p. 531). Fundación Santiago,.

Funtecha, H. (2004). Pasana-aw: Vignettes on Bisayan History and Culture, Volume 1. University of San Agustin.

Galang, Z. & Osias, C. (1936). Encyclopedia of the Philippines: the Library of Philippine Literature, Art and Science, Volume 1 (p. 44). Philippine Education Co.

Halili, M. (2004). Philippine History (p. 59). Manila: Rex Book Store, Inc.

In Focus: Mebuyan, the Goddess and the Music. (2009). National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved 13 May 2016

Jocano, F. (1968). Notes on Philippine Divinities. Asian Studies, 6(2), 169-182. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/CE72EP

Jocano, F. (1971). Myths and Legends of the Early Filipinos. Quezon City, Philippines: Alemar-Phoenix Publishing House, Inc.

Jocano, F. (1983). The Hiligaynon: An Ethnography of Family and Community Life in Western Bisayas Region (p. 17). Asian Center, University of the Philippines.

Medina, I. (2013). A Reconstruction of Philippine Social History from Tagalog Dictionaries and Vocabularies, 1600-1914). Asian Studies, 26.

Miller, J. (1904). Philippine Folklore Stories (pp. 57-64). Boston: Ginn and Company.

Montenegro, B. (2014). New asteroid named after Philippine goddess of lost things. GMA News Online. Retrieved 24 April 2016, from http://goo.gl/rUKfB3

Mythologies: A polytheistic view of the world (pp. 158-168).

Philippine Shamanism and Southeast Asian Parallels. (1973). Asian Studies, 11-12.

Raats, P. (1970). A Structural Study of Bagobo Myths and Rites. Asian Folklore Studies, 29, 1-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1177610

Ramos, M. (1990). Legends of Lower Gods. Quezon City, Philippines: Phoenix Publishing House, Inc.

Ramos, M. (1990). Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales. Quezon City, Philippines: Phoenix Publishing House, Inc.

Scott, W. (1974). The Discovery of the Igorots: Spanish Contacts with the Pagans of Northern Luzon (p. 18). New Day Publishers.

Scott, W. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press.

Vega, P. (2011). Serpent on Amaya eats moon just before real lunar eclipse. GMA News Online. Retrieved 8 May 2016, from http://goo.gl/NkRLzT

Zaide, G. (1939). Philippine history and civilization (p. 62). Philippine Education Co.

Written by Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito E. Batongbakal Jr. is the founder, editor, and chief content strategist of FilipiKnow, a leading online portal for free educational, Filipino-centric content. His curiosity and passion for learning have helped millions of Filipinos around the world get access to free insightful and practical information at the touch of their fingertips. With him at the helm, FilipiKnow has won numerous awards including the Top 10 Emerging Influential Blogs 2013, the 2015 Globe Tatt Awards, and the 2015 Philippine Bloggys Awards.

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net