Atlantis of the Philippines? Exploring the Mysterious “Lost Island” of San Juan

One of the most intriguing mysteries of our country’s geographic history involves a ‘vanished’ island off the northeastern tip of Mindanao.

Known as the island of San Juan (St. John), it was shown in ancient maps—larger than Bohol, maybe as big as Panay—completely detached from the massive Mindanao mainland.

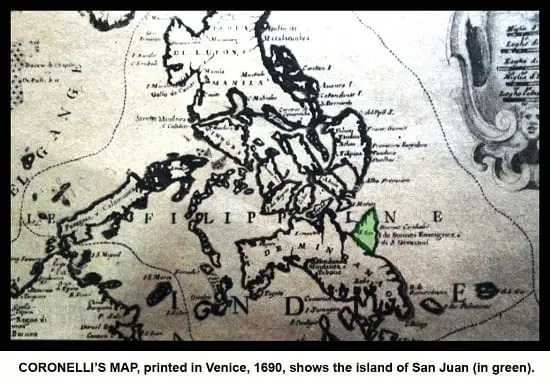

San Juan frequently occurred in over a dozen 16th to early 18th century maps. It was known to the Portuguese as the island of San: Joā through a 1537 portolan chart made by cartographer Gaspar Vargas.

Read: The Lost Tunnels Buried Deep Beneath Intramuros

In 1570, Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius featured “Ilhas de S. Johan” in his work Asiae Nova Descriptio, identifying it as a town of Cebu.

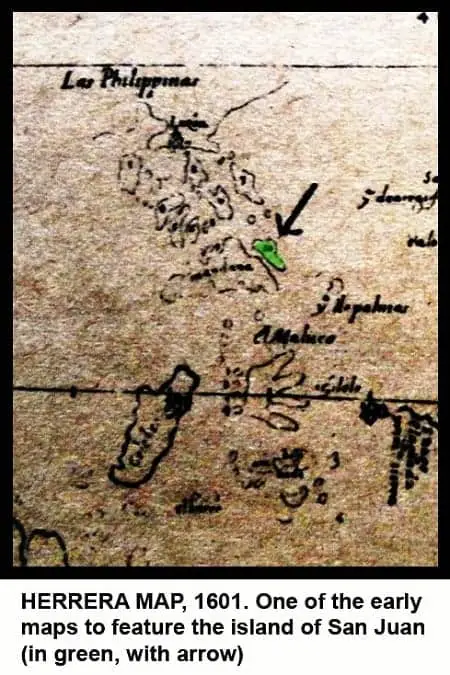

Five years later, it was reborn as a single, separate island off the northeastern coast of Mindanao, a depiction also shown in the 1601 map of Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas printed in Madrid—“Historia General de los Hechos de Los Castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Oceano.”

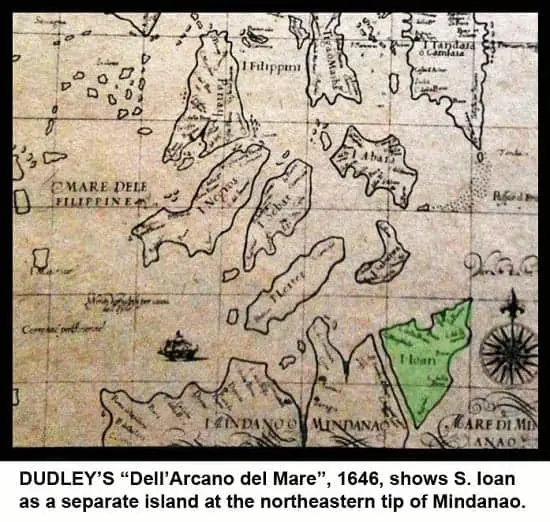

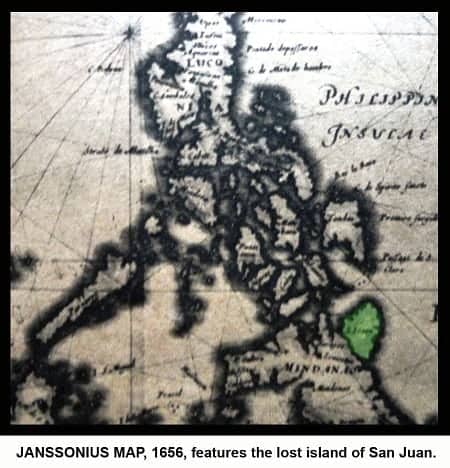

For two centuries, the enigmatic island was represented in maps done by Sir Robert Dudley (1646, Dell’Arcano del Mare, Florence), Dutchman Jan Janssonius (1656), and Vincenzo Coronelli (1690).

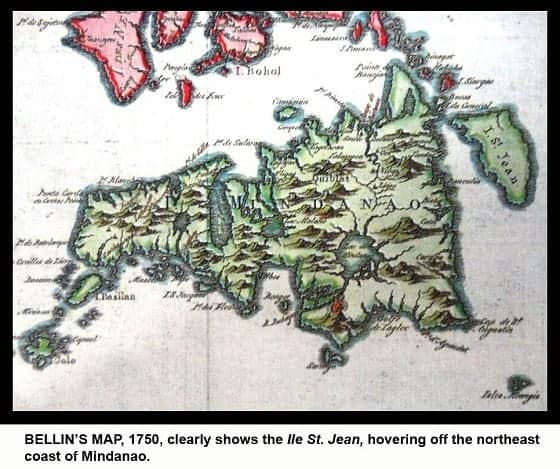

Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, the French cartographer who made maps of the Philippines in the 18th century, also included the island of San Juan in 1750.

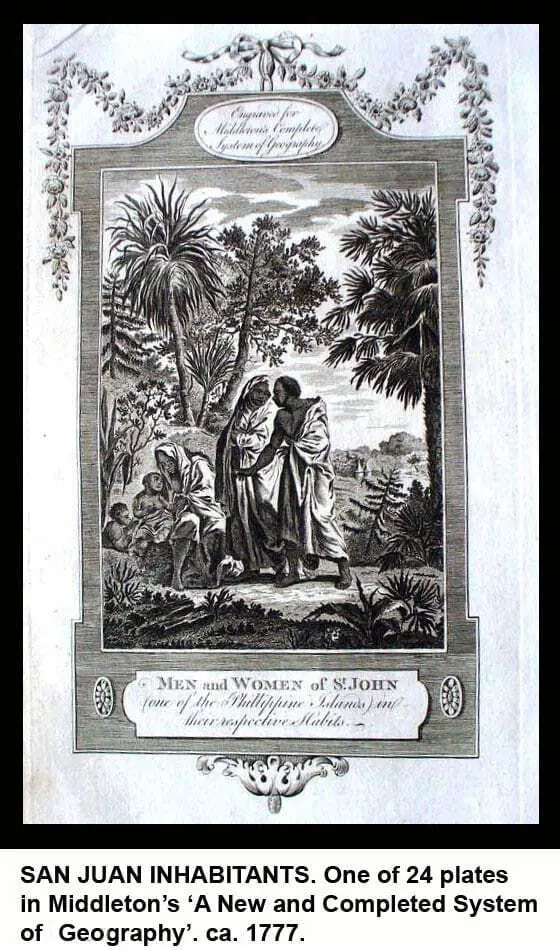

However, Christopher Middleton, a naval officer and cartographer, went one step further by including a print of the inhabitants of San Juan in his opus, “A New and Complete System of Geography,” a circa 1777-1780 series done on all the people of the world.

There were 24 plates, and the Philippines was represented by these San Juan natives more than the average oriental height, dark and curly-haired, amidst a backdrop of palms and fruit trees.

Despite how well-documented the island of San Juan had been, it was not present in the celebrated 1734 map drawn by Jesuit cartographer Murillo Velarde (the same map used to contest the Chinese claim on Scarborough Shoal), nor does he make mention of it.

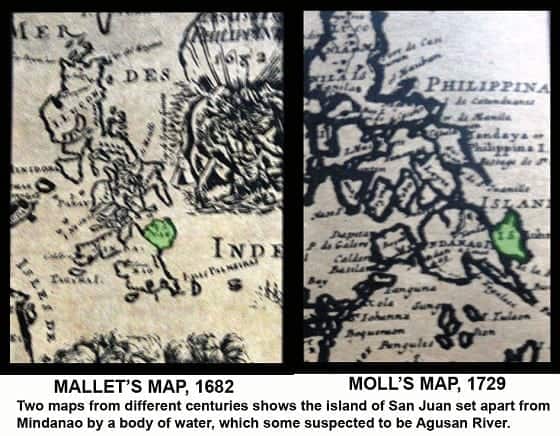

In subsequent maps, the island of San Juan was completely erased from the Philippine map. It was last seen on an 18th-century British map by Herman Moll and last heard of from the friar-chroniclers Buzaeta and Bravo at about the same time.

This led to many conjectures—from fanciful to fantastic—to explain the island’s sudden disappearance.

As late as 1969, antique map collector and artist Federico Aguilar Alcuaz theorized that it could have shared the same fate as the lost Atlantis, perhaps shaken by an earthquake or swallowed by the sea.

Writer E. Aguilar Cruz disputed this, saying that an island the size of San Juan could not have sunk without violence, whose rumble should have been remembered and recorded in history.

Perhaps, others contend, that it was the Agusan River, which old cartographers have drawn, dividing Mindanao and San Juan. The river must have silted through the years, thus, reattaching San Juan to Mindanao and making mapmakers realize that San Juan was not an island but part of a peninsula.

But why is it that, even as the old names of the other islands have remained, the name San Juan is completely unknown in the Surigao area, where it was approximately situated in modern-day Mindanao?

Where are its towns? And where have they gone?

The great Filipino historian Carlos Quirino, in the second edition of his book “Philippine Cartography,” insisted that San Juan was just an imaginary island first drawn by Herrera in 1601, a mistake subsequently copied by Sanson, Tirion, Coronelli, Hondius, Janssonius, du Val, Dudley, and others, in their maps.

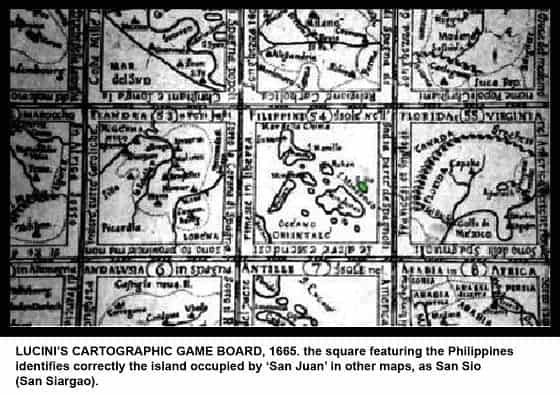

The mystery of San Juan was solved by a cartographic board game developed by Antonio Pucini in 1665.

The race-to-finish game consisted of squares where tokens were slid to reach a final destination–Venice. One of the squares featured the Philippines, where San Juan was replaced with San Sio (San Siargao), correctly identifying the island, which indeed lies on the northeast coast of Mindanao.

The name Siargao could have been confused with San:Joā. But because a board game was an unlikely place to shed light on a geographic mistake, this information was not taken seriously, and so the San Juan enigma persisted for more than two hundred years.

It was not until the more accurate Jesuit maps were drawn that things became clearer. These maps were based on information from inhabitants of Islas Carolinas (Caroline Islands), which placed the western Micronesian island groups of Palau and Sonsorol off the northeast corner of Mindanao.

These are likely the original San Juan, inadvertently appended by mapmakers to the Philippines.

Also Read: Mt. Pinatubo’s Eruption Aftermath, As Seen From Space

Of the two, Sonsorol seems to have a better fit. A Genoese navigator, Antonio Galvão, stated that San Juan consisted of two islands—as does Sonsorol. San Juan was said to lie at a latitude about 5-6º north, consistent with Sonsorol’s position.

Like the tale of the lost city of Atlantis, San Juan disappeared from our maps—but unlike Atlantis, the phantom island has been found again–its name, righted by Siargao, and its place, assumed by Sonsorol islands of Micronesia.

References

Abesamis, Ma. Elena, “Real or Imagined: The Lost Island of San Juan,” The Sunday Time Magazine, 25 May 1969, pp. 22-24.

Suarez, Thomas. “The Curious Case of the Island of St. John.” Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Periplus Editions (HK) Limited. 1999. pp. 172-173.

Fell, R.T., Images of Asia: Early Maps of South-East Asia, Oxford University Press. 2nd edition.1991.

Carte des Isles Philippines, Jacques Nicolas Bellin, c. 1760, part 2.

Written by Alex R. Castro

in Facts & Figures, History & Culture, Science and Technology

Last Updated

Alex R. Castro

Alex R. Castro is a retired advertising executive and is now a consultant and museum curator of the Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University, Angeles City. He is the author of 2 local history books “Scenes from a Bordertown & Other Views” and “Aro, Katimyas Da! A Memory Album of Titled Kapampangan Beauties 1908-2012”, a National Book Award finalist. He keeps 2 pop culture blogs: “Views from the Pampang” (2009 Philippine Blog Awards finalist) and Manila Carnivals 1908-1939. He is a 2014 Most Outstanding Kapampangan Awardee in the field of Arts. For comments on this article, contact him at [email protected]

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net